We are accustomed to looking back on the achievements of Greco-Roman antiquity with admiration and even awe. We often think of the Greeks, especially, as the originators of much that we prize in modern civilisation. This is held to be true, in particular, of Western science, believed, on this view, to have been a distinctive creation of the Greeks. To support such a claim, appeal is made to a long list of achievements, whether particular scientific discoveries or the establishing of scientific methods. Among the former would be listed Aristarchus’ heliocentric hypothesis, Archimedes’ principle, Hipparchus’ discovery of the precession of the equinoxes, Herophilus’ discovery of the nervous system, and many other examples. Among the latter would be cited the appreciation of the fundamental features of empirical research and the importance of the quantitative, mathematical expression of the regularities underlying physical phenomena.

Such an approach to the history of Greco-Roman science is fatally flawed on two related grounds, one specific, namely teleology, and the other more general, namely anachronism. By ‘teleology’ in this context is meant the interpretation of past events as if those involved could have anticipated the future, as if ancient science had modern science as its goal. Strictly speaking, what we now recognise as modern science – the research carried on in our modern laboratories and universities – is a phenomenon that does not antedate the beginnings of the nineteenth century. The term ‘science’ itself, as we understand it in ‘natural science’, is a nineteenth-century coinage. The institutions in which that work is nowadays carried on had no equivalents in the ancient Greco-Roman world. Nor is it just a matter of the lack of the institutions of modern science, but also one of an absence of the leading ideas that have been the driving force in its modern development. The whole modern idea of the importance of science as the source – via technology – of improvements to the material welfare of human beings has no ancient counterpart. Ancient research was clearly not directed towards the discovery of that modern idea, let alone harnessed to its implementation.

This takes us to the second, more general, problem, that of anachronism. The fundamental point is easily expressed. Neither the Greeks nor the Romans had an overarching concept that corresponds at all closely to our modern term ‘science’. True, that term derives from Latin scientia, but that, like Greek epistēmē, covers knowledge generally. Neither is confined to knowledge about natural phenomena, let alone to knowledge secured by a programme of systematic research governed by an agreed scientific methodology. Part 4 of this chapter, below, will be devoted to an investigation of the several, competing, ancient ideas concerning what kinds of knowledge are possible concerning natural phenomena, how they can be obtained and, in particular, how claims to have succeeded can be justified.

A whole series of other modern terms must also be said to be similarly potentially deceptive. ‘Astronomy’, ‘physics’, ‘geography’, ‘geometry’, ‘zoology’, ‘chemistry’ all derive from Greek terms, and in the first four cases they appear to be no more than mere transliterations of them. Yet in every case there are fundamental differences between the aims, scope and methods of the subjects as defined in Greco-Roman antiquity and in modern times.

This can be illustrated most easily with regard to the two terms ‘astronomy’ and ‘physics’. ‘Astronomy’ comprised, to be sure, the whole study of the stars and the heavenly region. What did that cover? The ancients sometimes distinguished between, on the one hand, the analysis and prediction of the movements of the heavenly bodies themselves, and, on the other, the prediction, on their basis, of events on Earth. The former corresponds, roughly, to ‘astronomy’; the latter, to our ‘astrology’. But although both Greeks and Romans had two names for the study of the stars – astronomía, astrología, and their Latin transliterations, astronomia, astrologia – both Greek and Latin pairs are used indifferently for both kinds of investigation. The ‘study of the stars’ generally comprised both and was not just confined to what we call ‘astronomy’.

In the case of the term ‘physics’, the problems are more complicated. The ancient Greek term physiké covered the whole of the study of nature – though what that comprised was debated – and so not just what we call ‘physics’ when we contrast that study with ‘chemistry’ and with ‘biology’. So the first point is that Greek physiké is broader than modern ‘physics’. But the ancient term encompasses a good deal more than what would nowadays be called ‘natural science’. In Aristotle’s treatise that passes by that name, we find discussions of abstract questions to do with time, space, infinity, and causation that correspond rather to what we might call ‘philosophy of science’ than to anything we would recognise as ‘natural science’.

Our first point in this introductory section is, then, that the Greeks and the Romans could not foresee the future development of science, and that certainly cannot be taken as their goal. Our second is that there are profound differences in the conceptual frameworks within which ancient and modern investigations were conducted. We can certainly not assume that ancient investigators approached the various areas of inquiry with anything like the same aims, presumptions, and preoccupations that we associate with their modern study. To those two points we must now add a third fundamental observation, which will occupy us again throughout Part 3 of this study. This relates to the basic disagreements that existed between different ancient authors, even within a single discipline, both on the subject matter of the discipline and on its proper methods. These disagreements are, indeed, as we shall see, a fundamental feature of Greco-Roman thought. The ancients not only did not have the modern idea of science: they did not all have the same ideas concerning each of the various areas of the investigation of Nature.

The preliminary observations of the last section carry important implications for the way we, as historians, approach the study of science in Greco-Roman antiquity. The way the subject used to be studied was to search through the remains of ancient writers to identify anticipations of modern results. That is totally unacceptable. What we have to do is to adopt the standpoint, not of modern science, but of the ancients themselves.

Our first task is to reconstruct how the ancients themselves conceived their subject matter, their aims and assumptions, their views both on the methods to be adopted and on what they hoped to achieve or thought, indeed, they had achieved.

The nature of the evidence available to us imposes severe limitations on that reconstruction. For a handful of ancient writers, we have a considerable body of original writings moderately well preserved in the extant manuscripts. Euclid, Archimedes, Ptolemy, Galen, as well as Plato, Aristotle, and Theophrastus, are, in that respect, comparatively well served. But for many others that is not the case. For some of the most important figures, indeed, not a single original work is extant in its entirety. That applies, for instance, to the fifth-century B.C.E. atomists, Leucippus and Democritus; to the fourth-century astronomer and mathematician Eudoxus; to the third-century biologists Herophilus and Erasistratus; and in other cases, such as that of the second-century B.C.E. astronomer Hipparchus, we have only a minor work, not his most important treatises.

In such instances we are reduced to reconstructing their thought from the secondary reports, but these are often critical or even manifest outright hostility. In evaluating those reports we must always ask why the ancient writer cites his predecessors or comments on them in the way he does. The problem of bias arises not just when an ancient writer cites his predecessors in order to refute them, but also when their quotations and comments are designed to evoke our admiration. One striking illustration of this is the way in which, in the second century C.E., Galen sets out to reconstruct the genuine teaching of the fifth-century B.C.E. doctor Hippocrates of Cos. The extant medical writings of the fifth and fourth centuries that we know as the Hippocratic Corpus are a highly heterogeneous set of works, and it is generally agreed by modern scholarship that none can be securely identified as by Hippocrates himself. But while Galen is aware of a ‘Hippocratic question’, that does not deter him from a reconstruction of the fundamentals of Hippocrates’ teaching, where it turns out that, in all essentials, Hippocrates was in agreement with Galen himself.

None of the processes of transmission by which ancient Greco-Roman science has come down to us is unmotivated. This is not just a matter of the potential bias in our ancient secondary sources. It is important to recognise the factors in play in the survival of some authors, and the non-survival of others. Two of the most important such factors are, first, the judgements made by ancient authors themselves on what passed as the best or most up-to-date work in a particular subject area, and second, the ideological presuppositions of the authors in question.

The eclipse of most Greek mathematics before Euclid may be set down, in part, to the perceived comprehensiveness of Euclid’s own work, the Elements, itself. Once the Elements existed, the need to preserve – that is, to copy out – the work of such men as Theaetetus and Eudoxus declined or even vanished. Similarly, the eclipse of Herophilus and Erasistratus reflects the perception that, in many areas of anatomy and physiology, their work had been superseded by that of Galen – a result that tallies with the judgement that Galen himself frequently expresses.

The second factor must also be given due weight. It is not fortuitous that many of the authors best represented by a considerable body of extant writings maintained one or other version of the view that the cosmos is the product of a benevolent, craftsmen-like, designing force—whether a transcendent god, or a divine force immanent in Nature—in other words, the philosophical position known as teleology. It is true that some whole works by those who took the opposite view are extant, the most notable being the De rerum natura of Lucretius in the first century. But in general the anti-teleologists—those who denied that the cosmos manifests design and who excluded appeal to the good or to final causes in the explanation of natural phenomena—are much less well represented in our extant sources than their opponents. That has the inevitable consequence of making our task, of reconstructing the ancient debate, much more difficult.

The problems of bias and lacunae in our sources must be constantly borne in mind. But that said, we must go ahead and make the best use we can of the evidence that is available to us. Our starting point must be such questions as the one we have mentioned concerning astronomy, namely what the ancients themselves included in the study of the stars. What, again, did they think the study of the ultimate constitution of physical objects comprised? How did they view the study of the human body, or the causes and cures of diseases? How, more fundamentally, did they believe that their theories or approaches could be established, justified, verified?

To answer those questions we have to go beyond a purely intellectual analysis of ancient Greco-Roman ideas and arguments. We have to ask why the ancient thinkers undertook the studies they did. What motivated them? How indeed did the study of Nature fit into the values of ancient society? Again, how did the thinkers in question make a living, or did they indeed have to do so? Clearly, for the reasons we have given, there was no such thing, in the Greco-Roman world, as setting out to pursue a career as a scientist as such. But if there was no funding for science as such, no equivalents to modern universities or research laboratories, we have to ask what roles were open to those who engaged in one or other area of the inquiry into Nature, and what support was available to them. They thought of themselves rather as ‘philosophers’ or ‘doctors’ or ‘architects’ or ‘mathematicians’, but as we shall see in part 5 the interactions within and between these groups provided a very different framework for the investigation of Nature from that provided by the institutions of modern science. There were, as we shall illustrate, some centres of patronage, and some important ancient researchers were beneficiaries. But patronage was limited and uncertain, and the motives of the patrons were the general ones of fame and renown, not a specific focus on the worthwhileness of science as such.

In the study that follows we shall follow through these methodological recommendations. We shall concentrate our attentions on the ancients’ own conceptions of their work, how that was to be defined, its methodology, why it was valuable or rewarding. They did not talk of science. Their discussion of those issues focused on terms that we can translate as ‘knowledge’ (epistēmē, scientia), art or skill (téchnē, ars), and Nature (phýsis, natura). But in their discussions those very terms were themselves problematised, as competing views were expressed both on what constituted knowledge or art, and on what the domain of Nature itself comprised. The next section will be devoted to outlining the problems of the pluralism of Greco-Roman investigations in the several areas of the inquiry concerning Nature.

We have insisted that ‘science’ is not a unified phenomenon in Greco-Roman antiquity. We have to unpack it into its separate strands—astronomy, medicine, mathematics, natural philosophy, and so on—while always guarding against the assumption that each of those corresponds at all closely with the modern study of that name. We shall here introduce an examination of the problem of the origins of ancient Greco-Roman scientific studies, and their periodisation, by way of a discussion of the different forms they took.

The pluralism of Greco-Roman science has two main manifestations. We have already noted that those who worked in the various branches of what we now call natural science did not present themselves as ‘scientists’, but rather as ‘philosophers’ or ‘doctors’ or ‘architects’ or ‘mathematicians’. The first main type of pluralism we have to take into account relates to the differences between those ancient categories. Then the second is the pluralism that existed within each.

The first type of pluralism is important not just because it gives us access to the categories in which ancient investigators defined themselves, but also because fundamental issues of methods and aims were at stake. We should not suppose, to be sure, that the boundaries between those ancient categories were rigid and impermeable or that the categories themselves were well defined and agreed. Some ancient writers chose deliberately to erode those barriers. Galen wrote a treatise entitled The best doctor is also a philosopher. For the Roman Vitruvius, the best architect also is. In both cases, ‘philosophy’ was associated with disinterestedness and with a deep theoretical grasp of the subject. But we should not fail to add that the effect of assimilating doctors and architects—or at any rate the élites among them—to ‘philosophers’ was to increase the prestige of those doctors and architects.

For some within the groups we have mentioned, the boundaries between them were not to be eroded but rather emphasised. The writer of the Hippocratic treatise On ancient medicine (written probably sometime in the early fourth century B.C.E.) is a good example. He explicitly criticises fellow doctors who import into medicine what he considers quite unnecessary and useless methods and assumptions—the new-fangled appeal to ‘hypotheses’ which he associates with what he calls ‘philosophy’, illustrating what he means by citing the mid-fifth-century cosmologist Empedocles. For this doctor, ‘philosophy’ does not provide ideas that medicine should try to approximate to: rather it stands for ideas and methods that medicine should avoid, and we shall be returning to what medicine has to offer as an alternative in part 4.

A second category invoked in On ancient medicine is that of ‘sophists’, and it is clear that the author disapproves of them as much as he does the study he calls ‘philosophy’. We have to be particularly careful here, since ‘sophist’ did not necessarily carry any pejorative undertones. The term could be used of ‘wise men’ generally, and when applied by Herodotus to Solon (Historiae, I, 29) or to Pythagoras (ibidem, IV, 95) should certainly not be thought to carry a negative implication. However, it came to be used, by Plato especially, of teachers and lecturers who generally travelled from city to city, accepted payment for their instruction, and often gained a very considerable reputation in the process. Plato is particularly concerned, of course, to dissociate Socrates from this new style of teaching, though for others—Aristophanes, for instance—Socrates was just another ‘sophist’. For our purposes, however, we must recognise first that we have good evidence, here, of teaching being a possible source of livelihood, and secondly, that the actual subjects taught by those called ‘sophists’ in Plato and elsewhere included many relevant to scientific inquiry. Some, such as Antiphon, were mathematicians. The polymath Hippias is said by Plato to have taught not just arithmetic and geometry but also astronomy and music. Though some of the medical writers in the Hippocratic Corpus criticise the kind of public lecture, or epídeixeis, associated with the sophists, other Hippocratic writings themselves illustrate that genre. These were composed by men who appear to have had little or no first-hand experience of medical practice themselves and were not doctors so much as lecturers.

Our first mode of pluralism relates, then, to the variety of roles available to those who engaged in one or other branch of the inquiry into Nature. We shall be following up in detail in part 4 the controversies that raged between different groups and individuals on, precisely, the question of the right method of undertaking such inquiries. But the second type of pluralism we mentioned is even more important for our present purposes here, for our understanding of what it would be to talk of origins and to attempt to establish valid periodisations in Greco-Roman science. This second type relates to the variety within each of the broad categories we have been talking about. The point is most easily illustrated with reference to ‘medicine’, though we shall then discuss more briefly similar phenomena where ‘mathematics’ and ‘philosophy’ are concerned.

To do justice to the variety of Greco-Roman medicine we must be clear, first of all, that there was far more to it than the extant writings contained in the Hippocratic Corpus and in such famous later authors as Celsus, Soranus, and Galen. This is not just because the extant medical literature is only a tiny proportion of what was written. The more important point is that the medicine we can associate with the writings of a literate élite is only one of the traditions of medical practice we know existed. It is true that our evidence for those other traditions is far more tenuous—scattered archaeological remains—and often indirect—references in sources that were generally highly critical. Even when we are told that some representatives of these other traditions composed writings, those have not survived—reminding us of the problems of the vagaries of transmission and the bias in our sources that we have mentioned before.

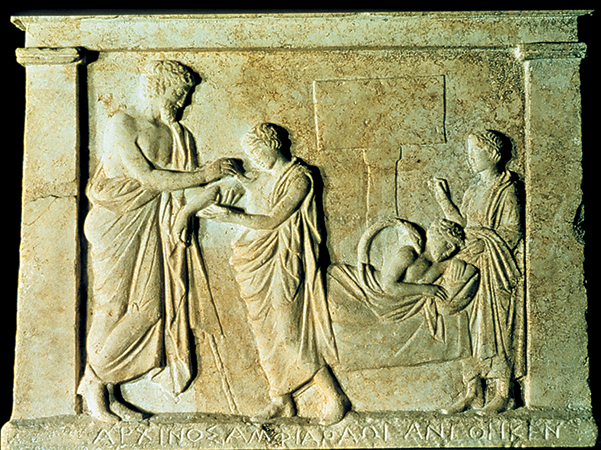

But difficult as it is to reconstruct these other traditions, we can be certain that they existed. First and most remarkably, probably the most popular style of healing practised in the Greco-Roman world was that practised in the shrines of the great healing gods and heroes, especially Asclepius. Although some healing cults antedate the fifth century B.C.E., the great expansion of temple healing and the foundation of imposing establishments such as that at Epidaurus are a phenomenon of the fourth century or later, that is contemporary with, or later than, our chief Hippocratic texts. Moreover, we can be sure of the popularity of these shrines not just in the classical period but down to the second century C.E. and later, when it is clear from the writings of the noted orator and statesman, Aelius Aristides, that their clients numbered among them well-to-do members of the literate elite.

The cult of Asclepius was not the only style of medicine that operated under the aegis of the divine or the supernatural. We hear from Plato and from the author of the Hippocratic work On the sacred disease that there were healers they call ‘purifiers’ who sold charms and incantations and claimed special knowledge as to which divinity was responsible for particular diseases and how they might be cured. These purifiers were not based in shrines to which the sick were taken: they sold their remedies to whoever they could get to buy them in the households of the sick. They too, however, invoked the divine in their accounts of disease and cure. Our two main early sources both condemn their work as superstitious charlatanry, but that, of course, is only one side of the story. We do not have the purifiers’ own side of the debate, but we have no reason to believe that they were put out of business by the rationalists’ criticisms. We should bear in mind that, so far as such acute diseases as ‘the sacred disease’ (epilepsy) were concerned, the Hippocratic doctors themselves had no effective means of cure despite the claims we find them making. The purifiers, for their part, could then have objected that Hippocratic remedies were ineffective and have argued that what they themselves offered was a set of beliefs that was more in tune with those of their patients. The Hippocratic counter to that was that the purifiers ignored the fact that the disease had a natural cause. ‘Nature’ here thus serves to mark out the Hippocratic style of medicine from that of its rivals which could be downgraded or dismissed as neglecting the essential regularities of natural phenomena.

The third and the fourth strands of Greek medicine are also badly represented in our extant sources. We hear of people called ‘root-cutters’ (rhizotómoi) and ‘drug-sellers’ (pharmakopōlai) who specialised in the collection, sale, and administration of herbal and other remedies. None of their own writings is extant, and we should in any case assume that few chose that medium of communication. One of our main early sources, Theophrastus, contrasts the ‘root-cutters’ with those he calls ‘doctors’ (iatroí) and he criticises what he considers the extravagant claims of the former. Yet it would be foolish to underestimate the knowledge that was available, outside and beyond the groups of the literate doctors, on the properties and effects of the rich store of materia medica used in the Greco-Roman world from earliest times, and foolish also to underestimate what the ‘root-cutters’ and ‘drug-sellers’ may have contributed to that store.

Finally we come to a fifth group of healers, the female practitioners who generally pass as maêai. That term is often translated ‘midwife’ and it is clear that childbirth and the care of the mother and baby were usually entrusted to skilled women. Yet that was clearly not their only role, for they were undoubtedly consulted on a wide range of other problems. Women healers would be the preferred recourse for most women patients. Reference to a male doctor would be a decision taken by the—male—head of household, but much medical practice—the great majority indeed—involved no such referral.

This rapid survey of the various styles of healing and healer for which we have evidence is enough to indicate that ‘medicine’ indeed took many different forms. It is essential to bear in mind that none of these ancient practitioners held legally recognised qualifications entitling them to practice. There were no professional bodies charged with overseeing medical education and responsible for maintaining standards of practice. The various strands of ancient medicine we have identified competed, therefore, with one another on far more equal terms than is the case nowadays, where what is called ‘alternative’ medicine is an alternative to practices that have all the weight of a legally established medical profession behind them as well as the authority of science itself. While, among some ancient Greeks and Romans, Hippocrates was a name to conjure with, the popularity of temple medicine was as great or greater than any on offer from the rationalist doctors represented in our extant texts. The rationalist doctors themselves, in any event, disagreed with one another as vociferously as they criticised their rivals from other traditions. From the Hippocratic writings, through the debates of the Hellenistic medical groups, down to Galen and beyond, competing theories of the origins of diseases, of the proper methods of treatment, of the nature of medical knowledge and practice themselves, were proposed in often highly acrimonious exchanges where livelihoods and reputations were evidently at stake. We shall be returning to consider this in greater detail in part 4.

The heterogeneity of ancient medicine in the Greco-Roman world is particularly striking. But we can illustrate pluralism also within what was termed ‘mathematics’ and ‘philosophy’ as well. First, the ancient Greek term mathēmatikē derives from the verb manthanein which has the general meaning of ‘to learn’. A mathēma is, then, potentially any branch of learning. For Plato, in the Republic (534e), the supreme mathēma is dialectic, the study of eternal, intelligible Forms, culminating in the grasp of the Form of the Good. Plato allows, however, of course, that there are other branches of learning too, notably those we call parts of mathematics, arithmetic and geometry, for instance, as well as astronomy and harmonics.

That might make it seem that ancient ‘mathematics’ at least covers, though it stretches beyond, what we mean by the term. Yet closer analysis reveals considerable complications. Three are particularly important for our purposes here: first, the dispute over the ontological status of the subject-matter of arithmetic and geometry; second, the application of the term ‘mathematician’ not just to astronomy but also to astrology; and third, the epistemological debates on the proper method in what we may think of as the mathematised sciences.

The first can be illustrated most economically with reference to Plato and Aristotle. For Plato, triangularity is an eternal, intelligible object whose ontological status is quite different from that of perceptible particular triangles (for example in diagrams) that are both inexact and perishable. Against that view, Aristotle argued that there are no separate, transcendent mathematical objects as such. Rather, what the mathematician studies is the mathematical properties of physical objects, in abstraction, to be sure, from the physical properties that they possess. This subordinates mathematics to physics, even while allowing that, given that abstraction from the physical properties of physical objects, mathematics is more exact than physics.

Mathēmatikos, ‘mathematician’, had a range of application that stretched well beyond those who studied arithmetic and geometry. Optics, harmonics, and astronomy were said by Aristotle (Physica 194a7 ff) to be among the ‘more physical’ of the mathēmata. Rays of light, sounds, and the movements of the heavenly bodies all belong to the physical domain, that is the domain of ‘nature’, although their study may involve geometry and arithmetic. But ‘mathematician’ was also frequently used of those engaged in what we should term ‘astrology’. That study, too, after all, depended on mathematical calculations, for example of the positions of the planets at birth—horoscopes—which then have to be interpreted according to what were represented as empirically secured correlations between the configurations of heavenly bodies and the fates of individuals. Here, indeed, was a style of ‘mathematics’ that could provide its practitioners with a living. Yet the status of astrology was anything but agreed. Some, such as Cicero, dismissed such modes of divination as superstition. Others, such as the sceptic Sextus Empiricus in the second century C.E., picked on astrology in particular in a general attack on the ‘mathematicians’. Among the dogmatists, too, the Epicureans considered much of the work of the astronomers, as well as the astrologers, as useless speculation. Among the defenders of astrology, however, were many of the chief theoretical astronomers of antiquity, notably Ptolemy himself. For him, both the study of the heavenly bodies themselves and predictions, on their basis, concerning events on Earth, are legitimate, but while the former is, or should be, exact, the latter is conjectural, based on assumptions which he claimed, nevertheless, to have stood the test of time (Tetrabiblos, I, 1).

The third complicating factor we mentioned relates to the dispute over the proper methods of inquiry to be adopted in the mathematised sciences, including, notably, both optics and harmonics, numbered, as we have noted, among the ‘more physical’ of the mathēmata by Aristotle. Insofar as they used geometry and arithmetic they could be assimilated to those mathematical studies themselves and be deemed exact. Yet that was not the only method or mode of investigation entertained. ‘Harmonics’, to take our best attested example, covered a wide range of studies. At one end of the spectrum there were inquiries directed to the needs of music-making, practical in orientation and unconcerned with the theoretical justification of the perceived contrasts between concords and discords. At the opposite end of the spectrum we find the recommendation, in Plato’s Republic (550d ff), to treat the study as a branch of number theory, the investigation, that is to say, of which numbers are concordant to which, with no regard for heard harmonies. But in between those two extremes, among those who agreed that both perception and reason have to be brought to bear, there were ongoing disputes as to whether arithmetic or geometry provided the proper model for analysis. Is sound a continuum, like a geometrical line, and so infinitely divisible? Or are the important relationships those that can be expressed as ratios between integers? The main ancient texts, from Aristoxenus in the fourth century B.C.E. to Ptolemy and Porphyry in the second and third centuries C.E., provide evidence of a wide spectrum of positions, not just with more or less weight being given to empirical data and to the judgement of practising musicians, but also with differing views on precisely what kind of mathematics this mathematical science should employ.

While both ‘medicine’ and ‘mathematics’ turn out to embrace a congeries of studies, one might, perhaps, expect that ‘philosophy’, including ‘natural philosophy’, would be more agreed and more univocal. It is true that after Aristotle, the two main positive philosophical schools, the Stoics and the Epicureans, adopted broadly similar views on what ‘philosophy’ comprised, even while they disagreed radically on substantive theoretical issues, such as on whether the cosmos is one or there is an infinite number of worlds, whether or not design and providentiality are at work, whether time, space, and matter are all infinitely divisible continua or all constituted by indivisible atomic units. Stoics and Epicureans differed also, to be sure, on methodological and epistemological questions. But both agreed that those questions—logic, the account one should give of the criterion of knowledge—belong to philosophy. Both also held that ethics does too—indeed, was the chief aim of philosophising. For both, ‘physics’, the study of Nature, formed the third component part of philosophy, though both subordinated physics to ethics. The study of natural phenomena was not to be carried on for its own sake, but rather to secure causal explanations without which we cannot attain the peace of mind, ataraxia, essential to happiness.

Thus far, at least in these schools, there was agreement, in the Hellenistic period, over the main component parts of ‘philosophy’. Before that, Aristotle had laid down broad distinctions between practical and theoretical studies, and within the latter, between ‘theology’, ‘mathematics’ and ‘physics’. Yet we should not underestimate the innovative features of the Aristotelian classification, nor the divergences in the models of ‘philosophy’ and the ‘philosopher’ before him.

The individuals we conventionally group together as the ‘Presocratic philosophers’ would certainly not have recognised themselves as all engaged in the same inquiry, with the same aims and the same subject matter. The term ‘philosophy’ is, in any case, rare in extant texts before Plato, and when used by Heraclitus (Fr. 35) of men who ‘inquire into many things’, it is not a term of approval. The Pythagoreans and Empedocles stand out as concerned with conduct, with the welfare of the soul, indeed, which they believed to be capable of reincarnation, after death, in other kinds of living creature. Others among the Presocratics offered cosmological accounts, frequently stressing the divine nature of the fundamental principles invoked in such accounts. Those whom Aristotle labels the physikoí, ‘naturalists’ or natural philosophers, attempted explanations of many different types of phenomena, ranging from earthquakes and eclipses to the differences in the physiological constitution of males and females. But although Plato criticises such explanations for failing to take the ‘good’ into account, we must be clear that for many of the naturalists, nature itself was divine, even though there was no question of their invoking personal gods to account for those natural phenomena.

These preliminary observations, revealing the diversity of application of some of the main classificatory terms, provide the fundamental basis for any attempt to answer the questions we raised, concerning origins and periodisation within Greco-Roman science. ‘Science’ itself has first to be unpacked into its main components, medicine, mathematics, natural philosophy, and so on. When we do that, we can see immediately that it would be absurd to expect to be able to answer the question of the origin of Greek medicine, if by that we mean the origins of a concern with trying to alleviate pain and cure disease. Such concerns are as old as the human race. The phenomenon we have to come to terms with is, rather, the emergence of that very pluralism of views and practices of medicine that we have outlined, ranging from appeals to the supernatural to the attempt to propose comprehensive naturalistic theories of diseases and their cures.

Similarly with mathematics: some use of numbers and of counting, in one or other of a great variety of recorded notations, is widespread, if not indeed universal, among human societies. Our explanandum here is rather the development, in Greece, of certain views about what ‘mathematics’ can or should include and of certain types of mathematical reasoning. We have to come to terms with the emergence of competing ideas about what mathematical knowledge consists in, as well as, eventually, the attempt to provide deductive proofs of mathematical theorems and set out the whole of mathematical knowledge in a single comprehensive framework.

Finally, there is pluralism in ‘philosophy’. The view that Greek philosophy as such originated with the work of a single individual, Thales, in the sixth century B.C.E. is one that stems ultimately from Aristotle. He suggested that the search for what he called material causes begins with Thales. But while we may accept that Thales offered a cosmological, or probably more strictly a cosmogonical account based on the principle water, we have seen that there were many different styles of philosophising in the Presocratic period. Our explananda here should not be the origin of ‘philosophy’ as such, but rather the emergence of those competing styles and aims, where intellectual leaders of very different kinds vied with one another for fame and prestige.

In each case the pluralism of the inquiries in question makes the task of assigning origins more difficult. At the same time, that pluralism provides us with an important clue as to how to deal with the problem. In each case, a key factor in the changes we need to focus on is the development of a particular framework of intellectual exchange, one in which alternative views could be expressed and their merits and weaknesses assessed. To understand the phenomena we encompass under the portmanteau expression of ‘early Greek science’, we need, above all, to focus on the emergence of rivalry and debate.

Now of course no explanation of phenomena as complex as those we have identified will be able to identify all the necessary, let alone the sufficient, conditions for the explanandum. But some positive and negative observations contribute something to the picture. First, negatively, the emergence of that framework of intellectual exchange is inconceivable in an ultra-authoritarian society, in a culture dominated, for example, either by a religious orthodoxy or by an overwhelming respect for past tradition. The Greeks admired such poets as Homer and Hesiod, such law-givers as the legendary Lycurgus, but certainly not to the point where such figures were beyond criticism. On the contrary, several of the early philosophers explicitly criticised Homer and Hesiod – as well as other philosophers – as we find, for example, in Xenophanes and in Heraclitus.

Secondly, and this time positively, the debates in medicine, in natural philosophy, in mathematics, can be paralleled, outside the more purely intellectual or theoretical domain, by those that occurred in the spheres of politics and the law. Many Greek citizens had extensive first-hand experience of debates in the political assemblies and in the law-courts, and although such experience was particularly extensive in the democracies, it was certainly not confined to them. In discussions of the best political constitution there is, indeed, a similar pluralism to that we have identified in medicine and in philosophy, where widely differing views or solutions to the problems could be canvassed in open debate. In the law-courts, where the dicasts acted as both judge and jury, and often numbered hundreds, styles of advocacy were developed that again have parallels in the broadly scientific domain. We cannot, to be sure, represent the scientific developments we are interested in as the direct outcome of political processes. But if we think of the general circumstances that led to the acceptability of the scientific debates, then their acceptability and indeed familiarity in the political and legal domain may be allowed to be a contributory factor.

When we redefine the problems to do with origins, we thus find that ‘Greek science’ has fundamental social and cultural roots, in the pluralism of Greek political forms and in the cultivation of modes of intellectual exchange in other spheres of Greek life. How far, we may now ask, do the traditional periodisations used in Greek history, from earliest times to the domination of the Mediterranean world by the Romans, bear on questions to do with the development of scientific thought? Four main periods are traditionally identified: archaic (before the emergence of the institutions of the city-state), classical (down to the conquests of Alexander), Hellenistic (down to the conquest of Alexandria by Rome), and Roman.

We may be brief on the first of these four, on the basis of the arguments we have developed on the themes of ‘origins’. Of course, Greeks always tried to cure diseases and used numbers: but that, we said, was not the point. The developments we have focused on, in medicine, mathematics, natural philosophy, in no case antedate the institution of the city-state. But did the transition from classical to Hellenistic bring with it important changes in the scientific domain? The founding of Alexandria itself was important, for while Athens continued to be the main centre for the practice of philosophy (as interpreted by such schools as the Stoics and Epicureans), many areas of mathematics and medicine underwent considerable development outside Athens and particularly in Alexandria itself. We shall be considering later the thorny question of the extent of patronage in the Museum founded by the Ptolemies in Alexandria and in the rival institutions set up in imitation of it in other cities in the Hellenistic world, although we should remark straight away that the motives of the patrons were not so much to support scientists as such, as to attract brilliant talents of every kind.

Intellectually speaking, certain changes that may be summed up in the phrase the ‘specialisation of the sciences’ do take place in the Hellenistic period, that is after the death of Aristotle. We have noted that there is more of a consensus then as to the component parts of ‘philosophy’, even while there were still heated debates on the substantive issues in physics, epistemology and ethics that it comprised. Again, the effect of Euclid’s comprehensive compendium of mathematical knowledge, the Elements, was to offer a distinctive model for mathematical reasoning. Some of those who applied that model confined their activities to mathematics or to those branches of physics that could be attacked mathematically. Archimedes and Apollonius are two notable examples.

However, the degree of specialisation should not be exaggerated. We have cited two examples, Vitruvius and Galen, where the boundaries between ‘philosophy’ and ‘architecture’ and between it and ‘medicine’ were challenged by authors who saw themselves as straddling them. In mathematics too, Ptolemy illustrates one notable case of a researcher whose interests spanned astronomy and astrology, harmonics and optics, as well as methodology or epistemology, represented in his short treatise On the Criterion. These instances all show that, for all the increasing specialisation in certain areas, there were still ‘generalists’, down to the second century C.E. at least, whose interests encompassed a range of inquiries.

It is true that from the Hellenistic period onwards, respect for tradition and authority, and especially for the great names of classical science, increased, and certainly after the second century C.E. innovation declined, and there is something of a shift in the style of our extant texts with the increasing preponderance of commentaries whose overt aim is not the presentation of original ideas so much as the preservation and interpretation of the great works of the past. Yet that development certainly did not mean the end to debate, as we can see from the often bitter polemics among the various commentators on Aristotle, such as that between the pagan Simplicius, based in Athens, and the Christian Philoponus in Alexandria, in the sixth century C.E. Nor did the commentary format preclude new ideas, for example in the analysis of the problems of what we might call dynamics, even though in some cases new ideas were presented merely as the correct interpretation of earlier authorities.

It is important to appreciate, therefore, that even though the political situation of the Greek city-states changed and much of their autonomy was lost in the aftermath of the conquests first of Alexander and then of those of Rome, that did not mean the end to what we have identified as a crucial element in Greco-Roman scientific inquiry throughout its history, namely the discussion and evaluation of alternative views in open argument and debate.

Thus far we have seen that those whom we think of as the foremost ancient Greek and Roman scientists had no single agreed conception of what it was they were about. Their aims, methods, and conceptions of their subject-matter all differed, and they saw themselves not as ‘scientists’ but rather as ‘doctors’, ‘mathematicians’, ‘architects’, or ‘philosophers’. Many worked towards a goal of understanding Nature, although there were plenty of disputes both about how to attain this and, indeed, on what ‘Nature’ itself comprised. This leads us to examine the question of just how any claim to have secured knowledge of natural phenomena was justified. The task of justification, indeed, was often uppermost in the minds of those who engaged in those disputes. Moreover, rivalry between contrasting points of view was not just a matter of who could provide the intellectually most satisfying account. Livelihoods, as we shall see, were at stake, as well as reputations.

First, however, we should attempt an overview of the chief arguments themselves. Speaking in the broadest terms, we may distinguish between two main approaches, each with several variations, sometimes opposed to one another, but on occasion combined. These are, first, the view that placed the emphasis on reason, and second, those that did so rather on observation and experience.

The view that knowledge claims have to be justified by, and based on, reason goes back to the Presocratic philosopher Parmenides at the beginning of the fifth century B.C.E. Perception, in his view, was to be rejected not just as fallible, but as radically deceptive. Many dissented from the conclusions that Parmenides himself drew from his study of what is—namely that plurality, coming-to-be, and change are all to be ruled out—but some agreed nevertheless that perception is untrustworthy, and reason and argument alone are to be considered reliable guides to truth.

With the concentration on reason and argument sometimes went a demand not just for truth but for certainty, and that was an important factor that stimulated the development of the notion of rigorous demonstration. Plato makes considerable use of the contrast between the certain (or what can be demonstrated) and the merely probable, between knowledge and true opinion. This is indeed one of the main ways in which he distinguishes true philosophy from the mere persuasion that others—‘sophists’, orators, politicians—trafficked in. In Plato’s case, the debates that took place in the law-courts and political assemblies were a powerful negative model: it was by contrast to them, as well as to the teachings of the sophists, that his own style of philosophy was to be judged superior, for it had not just the probable or the persuasive as its goal, but the objective truth, guaranteed by the rational account the philosopher could give to show that it was true.

Plato used the vocabulary of demonstration but did not define that term. It was one of Aristotle’s notable achievements to take the next step and offer such a definition. His Prior Analytics—the first treatise of formal logic—studied the valid modes of syllogistic reasoning, and in his Posterior Analytics he further showed that strict demonstration requires not just validity, but also premises that must fulfil very rigorous conditions, being true, primary, and explanatory of the conclusions. The ultimate premises, on which such demonstration depends, cannot themselves be demonstrated—to avoid the twin problems of circular reasoning and an infinite regress. Rather, they must themselves be indemonstrable self-evident starting-points: axioms, definitions, and hypotheses.

The main area from which Aristotle draws his examples is mathematics, even though there is a certain degree of artificiality or strain in recasting mathematical arguments in syllogistic form. Yet so powerful was the attraction of the model of demonstration he presented that versions of it served as an ideal not just in mathematics and the mathematical branches of studies such as harmonics and optics, but further afield still, in what we think of as the life sciences and even in medicine.

Aristotle himself, in the later sections of the Posterior Analytics especially, took some of his examples from such fields as botany. Yet in his actual practice in his own extensive investigations in zoology, he does not present his results in the form of syllogisms that conform to the criteria of strict demonstration set out in the Posterior Analytics. Indeed, they are not normally presented in syllogistic form at all, and there are explicit indications, for instance in the first book of On the Parts of Animals, that he worked with a looser notion of demonstration in contexts where he was certainly well aware of the complexities of the problems and of the provisional nature of his results.

Yet the attractions of the model of strict demonstration depended not just on Aristotle’s theoretical analysis, but also on the actual practice of Greek mathematicians. Euclid’s Elements, especially, showed how a very considerable body of mathematical knowledge could be presented in a single, comprehensive, axiomatic-deductive system. Subsequently, Archimedes’ statics and dynamics, for example, take the form of purely mathematical studies where a sequence of results is deduced from a limited set of postulates. His demand for demonstration comes out clearly in his work entitled De mechanicis propositionibus methodus. There a certain ‘mechanical’ method—one that assumes that geometrical shapes can be thought of as constituted by their indivisible segments and balanced against one another around a point treated as fulcrum—is explicitly said to be no more than heuristic. The results it yields, though correct, had, he insists, thereafter to be demonstrated using the rigorous mathematical methods of exhaustion.

Again, in the mathematical branches of such studies as harmonics and astronomy, claims for exactness depended on an appeal to the use of arithmetic and geometry. In the opening book of his astronomical treatise, the Syntaxis mathematica, Ptolemy argues for the superiority of ‘mathematics’ (here including mathematical astronomy) over both ‘theology’ and ‘physics’. The subject-matter of theology is quite obscure, and physics is a domain of conjecture. But mathematics can deliver unshakeable results, guaranteed precisely by the use of arithmetical and geometrical arguments.

It is more surprising to find the model of strict demonstration ‘in the geometrical manner’ advocated as the ideal further afield, even in such a study as medicine. Galen, who was himself an original formal logician, held that such demonstration is to be practised by the medical theorist as far as possible, and in his own discussion of the seat of the various vital functions, claimed to demonstrate that the seat of the nervous system is the brain, and that of the spirited part the heart. But the recurrent problem in the application of the notion of axiomatic-deductive reasoning to the investigation of natural phenomena was the difficulty of securing propositions that could indeed count as indemonstrable self-evident axioms. The paradox was that Galen himself was a superb empirical investigator of such matters as the detailed courses and functions of particular nerves. What we might call his anatomical demonstrations, for example his discovery of the recurrent laryngeal nerve, were of the highest order, but did not satisfy his own strictest criteria for a demonstration unless or until recast in a formal logical mode, and derived from axiomatic starting-points.

Beside the justification of knowledge claims by appeal to reason and argument, we find others that referred, rather, to observation and experience. Here the key terms include ‘perception’ (aísthēsis), ‘research’ (historía) and several that span experience and testing (empeiría, peîra). Where Parmenides had rejected perception as deceptive, already in the Presocratic period there were others who restored it at least in a limited role. For Xenophanes already, before Parmenides, the truth is not revealed but found by searching over time. Anaxagoras in the late fifth century states the important principle of using what appears (the phainómena) as the ‘vision’ of the obscure, a view endorsed by, among others, the atomist Democritus. What this involved, in many cases, was inferring explanations of obscure phenomena on the basis of perceived, or suggested, analogies with more familiar ones.

The medical treatise On Ancient Medicine, which we have already cited, provides one of the most sustained critiques of a reductive dogmatism which, in the author’s view, was a wholly mistaken importation into medicine from philosophy. He particularly objects to those who attempted to derive the whole of medicine from a limited number of ‘hypotheses’, such as hot or cold or wet and dry. Although we cannot identify precisely whom he is attacking, the views of his opponents bear obvious similarities to some of those of the Presocratic cosmologists who attempted to explain the multiple diversity of phenomena on the basis of a single, or a limited number of principles.

What the author of this work offers in place of the use of ‘hypotheses’ is a conception of medicine based on experience. This is the ancient, tried and tested, method by which medicine has made its discoveries and can indeed make more. Arbitrary postulates are irrelevant. As in other arts, there are good and bad practitioners, where in part, at least, the appeal is to results. This is one of the clearest early statements of the point of view that for a study to be legitimate it does not have to yield certainty. Against those who insisted on incontrovertibility, this medical theorist counters that medicine is a genuine art even though certainty is only rarely attained.

In many cases, to be sure, attempts to develop empirical methods of investigation and to expand the data base under consideration met with only limited success. We may mention one such case, the study of the void, before turning to other examples where empirical methods bore greater fruit.

The debate on the void forms part of the set of issues on which the chief positive Hellenistic philosophical schools took up sharply opposing positions. Where, following Plato and Aristotle, the Stoics represented space, time and matter as all infinitely divisible continua, the Epicureans developed the views of the fifth-century B.C.E. atomists, Leucippus and Democritus, according to which all these ultimately consist of indivisible units. Both Stoics and Epicureans took perception as the ultimate criterion of knowledge: yet this physical dispute was, of course, not to be resolved by a mere appeal to what anyone could observe. On the contrary, both sides appealed to the same limited set of phenomena, interpreting them differently according to their underlying assumptions. Thus the Epicureans thought that for movement to take place, there had to be gaps between objects through which they can move. The Stoics appealed to the fact that fish swim through water as an indication that no such gaps are necessary, though the Epicureans would have countered that they do exist even though they are below the level of observation.

One more resolute attempt to bring new empirical facts to bear shows the difficulties of doing so. In the first century C.E., Hero of Alexandria contributed to a number of disciplines, ranging from geometry to the technical analysis of the construction of war-engines. In the treatise devoted to the study of air, Pneumatics, he criticises those who had put forward theories without offering tangible proof of the results. The philosophers are taken to task for relying on argument alone. Hero undertakes to show his own views—which include the idea that a vacuum can be produced artificially—by appeal to perceptible phenomena, and he accordingly sets up a series of tests that exhibit, for instance, that air can be evacuated from an air-tight vessel or forced into it under pressure. The tests are described with some care, and yet they are clearly inconclusive. The continuum theorists whom Hero hopes to refute would have interpreted the results in terms of their own assumption of the elasticity of matter and denied that they had shown that a void can be created artificially.

It is often claimed that one of the great weaknesses of Greco-Roman science is the failure to appreciate the importance of experiment. But that is a gross oversimplification, influenced by anachronistic criteria. As the last example from Hero shows, attempts to set up artificial circumstances to investigate the phenomena were sometimes made, even when they did not lead to a resolution of the problems. Nor is Hero’s an isolated case. In the study of reflection and refraction in Ptolemy’s Optics, extensive tests are carried out, both to demonstrate the laws of reflection and to determine the amounts of refraction for three different pairs of media: air to water, air to glass, and water to glass. The investigation of refraction illustrates another problem with some ancient experiments, namely that the results have evidently been adjusted to tally with the—unstated—theoretical law that the study is directed to exploring. In this, and many other cases, the tests that we find in Greek or Roman writers serve rather as an extension of the evidence appealed to, not as a way of discriminating between alternative hypotheses thought of, initially, as of equal standing. The ideal of conducting experiments on the basis of neutral assumptions as to their outcome does not tally with the usual ancient view.

One of the most striking developments of empirical methods, however, has yet to be mentioned. This is the investigation of problems in anatomy and physiology, using dissection, and sometimes the vivisection, of animals, and even, in limited circumstances, also of humans. The first Greek to apply these methods to animal subjects was Aristotle. His zoological studies were not carried out in any inductivist spirit of fact-collecting for its own sake. On the contrary, he clearly states that their aim is to reveal the causes of the phenomena, especially the formal and final causes, though his pursuit of that aim certainly shows that there was far more to his work in zoology than the search for axiomatic-deductive demonstrations on the model of the Posterior Analytics.

The use of human subjects was largely confined to the work of the Alexandrian biologists, Herophilus and Erasistratus in the early third century B.C.E., even though human osteology continued to be taught at Alexandria down to Galen’s day. Three features of this work are fundamental. First, it depended on the support of the Ptolemies. Our chief source, Celsus, records, in relation to human vivisection, that this was carried out on criminals received out of prison from the kings. Secondly, the practice of anatomical dissection and vivisection in the early Hellenistic period undoubtedly led to a series of important discoveries, not least that of the nervous system itself. But thirdly, the method was, and remained, intensely controversial. Vivisection was rejected, by Celsus himself, for instance, as cruel: but some also argued that, for the doctor, dissection was not necessary (on the grounds that all the anatomical knowledge he needs will come from his clinical practice) or even that its results were irrelevant since they related not to the living, functioning body but to the dead. Many of the Hellenistic doctors, notably those known as the Empiricists and the Methodists, adopted a negative attitude towards both dissection and vivisection, although as we have already had occasion to note, that did not stop Galen in the second century C.E. undertaking extensive anatomical investigations using those methods.

Throughout Greco-Roman antiquity, the question of which methods are to be used in which areas of inquiry was as disputed as substantive issues to do with everything from the causes of diseases, through the fundamental constituents of physical objects, to the correct explanations of musical harmonies or the movements of the planets. The disputes on many of those substantive issues often involved, indeed, those second-order methodological questions. Theorists sometimes sought to win the substantive debate in part by arguing that their opponents had mistaken views on the nature of the subject-matter itself or on how it should be investigated. The opponents’ proposals must be wrong, since their methods were.

The recurrent feature of Greco-Roman science that this section has focussed on is the need for justification. But the pluralism we illustrated in the previous section extends to modes of justification themselves. Our next task is to review the institutional frameworks within which ancient Greco-Roman investigators operated, where we shall argue that the very rivalry between competing groups and individuals served as one of the most important factors, providing one of the chief intellectual frameworks within which ancient investigations were carried on.

What were the institutions within which Greco-Roman scientific research was conducted? How did the individuals earn a living, or did they need to do so? How far were they dependent on patronage, and where that existed, what were the motives of the patrons?

We have already indicated something of the gulf between the ancient and the modern world. The ancients had no research laboratories sponsoring the work of scientists. Nor were there scientific departments in universities, for there were no universities at all. To be sure, institutions of learning existed—the schools of philosophy at Athens especially—but those who worked there generally earned their living by teaching, if they earned a living at all. The Ptolemies set up a museum as well as an imposing library at Alexandria, and these were imitated in other Hellenistic cities. But none of these was set up specifically to foster scientific research. The Ptolemies supported poets, literary critics and grammarians as much as they did such figures as Herophilus and Erasistratus. As we learn from Philo of Byzantium, they also subsidised some who worked on problems in mechanics, but that was in a very practical connection—namely the improvement of catapults and other weapons of war. Patronage of science in the Greco-Roman world was, we may conclude, limited in scope and uncertain in application, depending as it always did on the whims of patrons. So far as the Ptolemies themselves went, it is clear that one of their chief motives was simply fame and prestige.

The investigators we have been discussing could and did earn money from particular services they provided. Doctors of all types were paid to tend the sick, and from the classical period onwards some were given retainers by cities to serve as public doctors, while later immunity from certain taxes was granted to some. Architects were paid not just to build buildings: Vitruvius, for instance, tells us that one of his duties was to oversee the construction and maintenance of catapults and ballistae. Astrologers always had a large clientele.

To these activities we must add possibly the most important function of anyone who laid claim to special knowledge of any kind, namely as teachers. It was not just philosophers, but also mathematicians and doctors, who earned a living or supplemented their means in that capacity, and in the last case especially, the teaching did not just serve the purposes of satisfying the curiosity of those interested in the subject purely for general educational reasons. Most of those the doctors taught were aspiring practitioners themselves.

The styles of teaching and the contexts in which it occurred varied widely. The so-called sophists of the fifth century B.C.E. often used the public lecture, both as a means of instruction itself and as a way of attracting pupils on a more permanent basis. We hear, too, already in the classical period, of open, public debates between rival lecturers. These debates, we suggested, share some of the features of those held on matters of state, in the political assemblies or between prosecutor and defendant in the courts of law. According to the fourth-century B.C.E. Hippocratic treatise On the Nature of Man, some such debates were adjudicated by the lay audience themselves. They thus served not just as a forum for the intellectual exploration of abstract problems, but also as an important means of building up a reputation. The aggressive adversariality of many Greek intellectual exchanges owes something to the models provided by politics and the law: but it also reflects the need that potential intellectual leaders of all kinds had to establish a name for themselves. This they did not just by advocating their own point of view, but also by attempting to demolish those of their rivals, their predecessors and contemporaries, including, in many cases, their own teachers.

But Greek teachers did not always operate just as individuals. Both in philosophy and in medicine, especially, groups banded together to form ‘schools’. Some of these, such as Plato’s Academy, Aristotle’s Lyceum, and the Epicureans’ Garden, possessed buildings, which often included a library. In Roman times, the heads of these schools even received stipends from the State.

However, it is important not to exaggerate the formal nature of the establishments in question, nor to misinterpret what belonging to a school signified. Pupils did not attend to gain degrees serving to licence them as teachers in their turn: that was a phenomenon of the late medieval universities and marks a fundamental contrast between their function and that of ancient academies. Ancient institutions had no formal curricula. Although, as noted, both the Epicureans and the Stoics had definite ideas concerning the constituent parts of ‘philosophy’, individual members of those groups differed in their own particular interests. Within Plato’s Academy there were mathematicians and aspiring statesmen as well as those more attuned to Plato’s own metaphysical preoccupations. The range of interests of Aristotle’s associates was equally wide; nor should we forget that Aristotle had been a member of Plato’s Academy for some twenty years.

It was not the business of these philosophical schools to standardise the interests of their members, let alone to establish an orthodoxy to which all had to subscribe. It is true that the Epicureans were known for greater loyalty to their founder’s views. But in general, what the founder stood for was a matter of interpretation in each generation—as we can see from the debates within those who called themselves Platonists about the teaching of Plato himself.

Yet in the context of rivalry between schools, the disagreements between them were important. The schools competed for pupils, though they had no way of holding them permanently once they had secured them. As with individual teachers, so too with the schools themselves, one of the chief vehicles for creating and maintaining a reputation was the public debate, and again as with individual performances, destroying the opposition’s case was as important an element as constructing your own.

In this context, the role of the philosophical schools was to form more or less tightly-knit alliances for defensive and offensive argumentative purposes. Moreover, very similar points apply to groupings outside philosophy, including even in medicine. It is true that some of the so-called medical schools, such as those associated with Cos and Cnidos, or the later sect known as the Dogmatists, are largely the fabrication of commentators or historians. But even when we can be more confident that certain teaching was shared and transmitted within the group, as with the Empiricists and the Methodists of the Hellenistic period, the model we should use to assess them is of course not that of a modern medical school, but rather that provided by the ancient philosophical institutions we have discussed. The doctors, like the philosophers, sometimes banded together to defend, in argument, their views of the nature of medicine, their theories of disease and cure.

In the absence of other types of institution, such as those in which science is nowadays pursued, these ancient ‘schools’ provided an important part of the framework for investigations in philosophy, medicine and other fields of inquiry. The rivalry between individuals and between groups itself may be considered an important institution, stimulating the critical analysis of the theories on offer, as well as influencing the often aggressive style of analysis conducted. The pluralism we have remarked in different areas of ancient inquiry itself reflects that rivalry, as different individuals or groups strove to make or to maintain their reputations. We can see the relevance of this framework even in such an apparently purely intellectual matter as the development of axiomatic-deductive demonstration. We have pointed out what this owes both to the practice of mathematics and to the theoretical reflections of Aristotle. The extra feature that needs to be borne in mind, when evaluating the influence of proof in the geometrical manner in other areas of inquiry, is that, in the context of rivalry that we have described, incontrovertibility, if it could be secured, was something of an argumentative trump card. If certainty be claimed, then the debate was won. The recurrent problem was that for those purposes what was needed was not just valid inference, but true, self-evident, indemonstrable axioms, and in practice it was often the case that no sooner was incontrovertibility claimed, than that claim was itself controverted.

Science takes many different forms in different ancient cultures. Aspects of Babylonian and Egyptian investigations, in such fields as astronomy and mathematics, will be discussed in relation to the Greeks in a subsequent chapter. The achievements of Chinese researchers are the subject of another volume in this series.

The object of this introductory chapter here has been to examine the framework within which the Greeks and Romans operated. There are indeed many more features to this than we have been able to discuss here. There are many important, interesting and idiosyncratic individuals, whose ideas defy generalisation. We must repeat the reservations we have expressed concerning the limits of what we can hope to explain.

But certain fundamental ways in which Greco-Roman scientific investigations reflect Greco-Roman society are important. The pluralism we have emphasised is doubly significant. On the one hand it provides a warning for us as interpreters and historians. The phenomena we are dealing with under the rubric of ancient Greco-Roman ‘science’ are not the homogeneous, unitary set of inquiries that that label might suggest. The ancient investigators in question were not to know they would be thought of as ‘scientists’. They could not foresee the future. Their aims and methods were in every case different from those we associate with modern science, and different even from those who, from the seventeenth century, have appealed to the Greeks as models for their own work. On the other hand, that ancient pluralism highlights an important feature of Greek and Roman work. Some brief concluding comparative observations will serve to underline the point.

As in many other ancient societies, much of the research undertaken in such a field as astronomy was the work of members of a literate élite. But in Greece and Rome this did not consist of a closed or exclusive scribal class. It is true that the extent of Greco-Roman literacy is a highly disputed question and it would be very unwise to exaggerate the numbers of those who could do more than just write their own names, if that. Moreover we have had occasion to remark that medical lore was far from confined to those who were in a position to compose treatises on the subject. Yet access to writing was sufficiently widespread to play a significant part in the transmission of ideas in the Greco-Roman world from the classical period onwards, even while most teaching, indeed most intellectual exchanges, were a matter of face-to-face communication mediated in the oral mode.

Again, as in many other ancient societies, the work of astronomers, cosmologists, even medical theorists, was often used to underpin a political or ideological message. The notion that the universe is the product of benevolent design is one that had significance well beyond the questions to be borne in mind in the investigation of the movements of the planets or the anatomy or physiology of humans or other animals. But there was much less agreement, in Greece and even in Rome, about what the political ideal itself was than existed, for example, in ancient China or Babylonia. So while the Greeks often compared the macrocosm with the microcosms of the body and the state, as did the ancient Chinese, there is this difference, that there was far greater consensus, in China, on how that macrocosm, those microcosms, were to be understood than there was in Greece. The pluralism we find in Greco-Roman scientific investigations mirrors the pluralism of political viewpoints, for debate on the latter continued even when there was no real alternative but to accept Roman imperial rule.

But if debate, indeed dispute, are endemic in Greco-Roman culture, this was not just because the Greeks, say, were especially disputatious by nature. Rather that disputatiousness reflected a basic feature of how most intellectual leaders made their careers. To make their names they often sought the prestige attached to winning, and being seen to win, the argument with rivals in public debate. So far as philosophers, medical theorists, and others went, this was the chief means to acquiring the reputation on which their livelihood, at least as teachers, depended. The contrast here would be with the relatively secure position guaranteed by the credentials of the temple scribes of Babylonia or by access to the imperial civil service and to such institutions as the Astronomical Bureau in ancient China.

The recontextualising of ancient Greco-Roman science enables us to set some of its admired achievements as not just the products of individual genius, but the reflection of the development of particular frameworks for intellectual exchange. Some of the main features of those frameworks have been outlined here. The exploration of all the complexities of the work of different types of investigator, at different periods, will be carried out, in the chapters that follow, in as much detail as space permits.

Geoffrey E.R. Lloyd - John Vallance

References

- Burkert 1972:, Walter. Lore and Science in Ancient Pythagoreanism. Cambridge (Mass.): Harvard University Press, 1972. (Engl. rev. ed. of: Weisheit und Wissenschaft, Nürnberg: H. Carl, 1962).

- Edelstein 1967:, Ludwig. Ancient Medicine: Selected Papers. Edited by Owsei Temkin and Clarice Lilian Temkin. Baltimore (Md.): The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1967.

- Frede 1987:, Michael. Essays in Ancient Philosophy. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1987.

- Fritz 1971:, Kurt von. Grundprobleme der Geschichte der antiken Wissenschaft. Berlin-New York: W. de Gruyter, 1971.

- Furley 1987:, David John. The Greek Cosmologists, vol. I: The Formation of the Atomic Theory and Its Earliest Critics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

- Knorr 1975:, Wilbur R. The Evolution of the Euclidean Elements. Dordrecht-Boston: D. Reidel Publ. Co., 1975.

- Kudlien 1967:, Fridolf. Der Beginn des medizinischen Denkens bei den Griechen: Von Homer bis Hippokrates. Zürich-Stuttgart: Artemis Verlag, 1967.

- Lloyd 1979:, Geoffrey Ernest Richard. Magic, Reason, and Experience: Studies in the Origin and Development of Greek Science. Cambridge-New York: Cambridge University Press, 1979. (It. trans.: Magia, ragione, esperienza, Torino: Boringhieri, 1982).

- — 1983:. Science, Folklore, and Ideology: Studies in the Life Sciences in Ancient Greece. Cambridge-New York: Cambridge University Press, 1983.

- — 1987: The Revolutions of Wisdom: Studies in the Claims and Practice of Ancient Greek Science. Berkeley (Calif.): University of California Press, 1987.

- — 1991: Methods and Problems in Greek Science. Cambridge-New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

- — 1996: Adversaries and Authorities: Investigations into Ancient Greek and Chinese Science. Cambridge-New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- Netz 1999:, Reviel. The Shaping of Deduction in Greek Mathematics: A Study in Cognitive History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- Neugebauer 1957:, Otto. The Exact Sciences in Antiquity. Copenhagen: Munksgaard, 1951. (2nd ed.: Providence: Brown University Press, 1957).

- Nutton 1988:, Vivian. From Democedes to Harvey: Studies in the History of Medicine. London: Variorum Reprints, 1988.

- Sambursky 1962:, Samuel. The Physical World of Late Antiquity. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1962.

- von Staden 1962:, Heinrich. Herophilus: The Art of Medicine in Early Alexandria. Cambridge-New York: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

- Vegetti 1979:, Mario. Il coltello e lo stilo: Animali, schiavi, barbari e donne alle origini della razionalità scientifica. Milano: Il Saggiatore, 1979.

- Vernant 1962:, Jean-Pierre. Les origines de la pensée grecque. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1962. (4th ed.: 1981).

- — 1965: Mythe et pensée chez les Grecs: Études de psychologie historique. Paris: F. Maspero, 1965.