From the earliest stages of their religious experience, the peoples of the ancient world – both classical and Eastern – perceived in the celestial vault the seat of a mysterious power that governed the alternation of solar days with lunar and sidereal nights, the rhythm of the seasons, and the regulation of atmospheric phenomena. A similar force was imagined to dwell within the Earth, responsible for vegetation, volcanic and seismic events, and storms. Consequently, a spontaneous process of deification began, attributing divine status to the Heavens, the stars, and the Earth. This process took different forms depending on the historical circumstances and traditions of each people, shaping and reshaping their respective pantheons, often influenced by external cultures.

Among the celestial bodies, the Sun and the Moon were the first to be worshipped as distinct deities, present in every pantheon. In the deification of the heavens, the nocturnal image of the star-filled sky, illuminated against a dark backdrop, held particular significance. A radical transformation occurred, however, with the rise of complex urban societies and organized states. These developments necessitated a more structured configuration of cults, assigning distinct physiognomies and functions to each deity. Among these, special prominence was given to those embodying the darker forces of nature, whose power extended over all living beings.

Simultaneously, a need arose for theological frameworks tied to emerging, necessarily mythic, interpretations of the cosmos and human destiny. The creation of myths was influenced by the emotions and reflections that accompanied daily technical and intellectual experiences. In the most creative minds, mýthos served as a catalyst for critical lógos. The human world was thus enriched by invisible protagonists, imagined in anthropomorphic, zoomorphic, or vegetal forms, and at times represented by aniconic wooden or stone symbols. These figures, though endowed with superhuman powers, shared human thoughts and passions.

Aniconic symbols were eventually supplanted by anthropomorphic or theriomorphic representations, which signified either beneficent or malevolent roles. This partial assimilation of the divine to the human allowed devotees to feel the gods perpetually present among them, prompting a clearer definition of each deity’s domain – both those presiding over the living and those ruling the underworld. The visible stars, already used to mark seasonal changes and timekeeping, came to be seen as exerting a decisive influence on human character and fate. Regulating interaction with these often feared or invoked presences led to the development of magical practices aimed at binding the gods. In the Greek world, for instance, the cult statue linked the deity to the temple (naós), the ritual invocation (epíklēsis) was considered irresistible when performed in a consecrated space, and the deity’s name inscribed on the altar established its divine proprietorship.

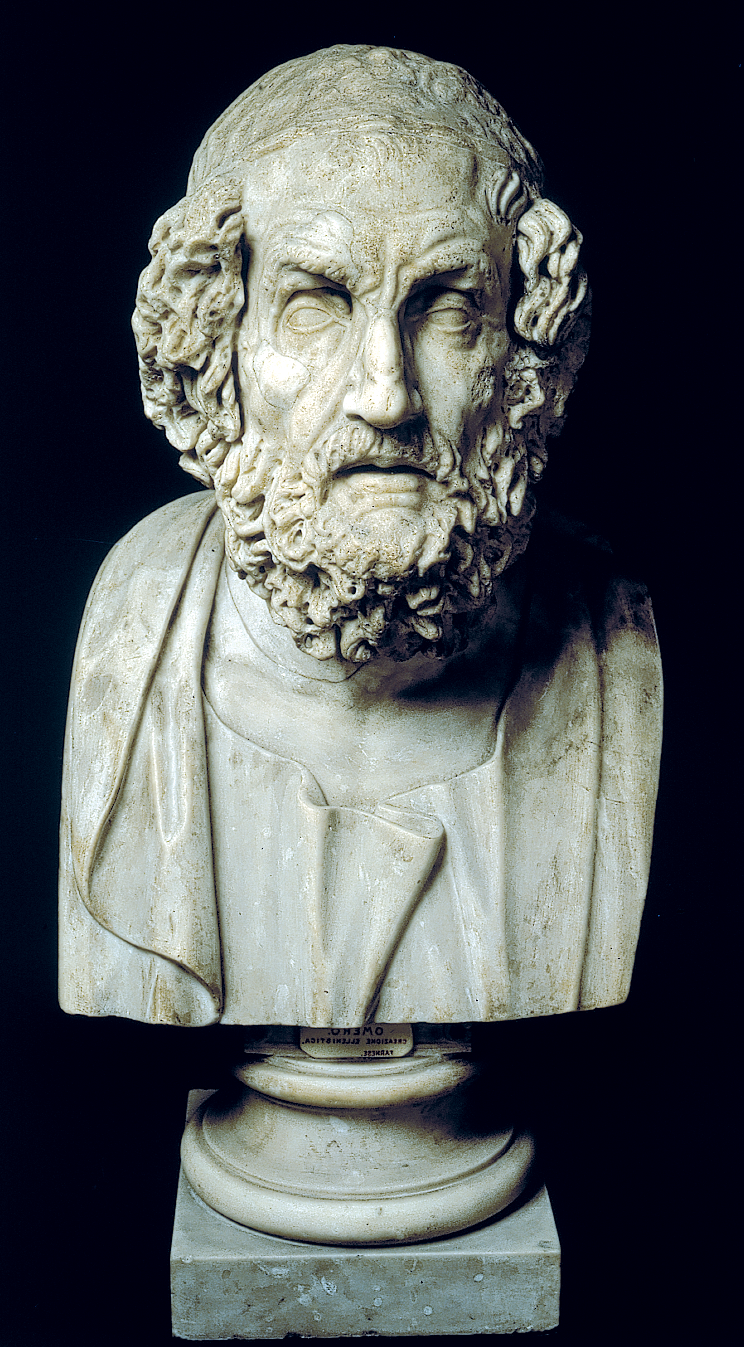

This interconnection – clearly observable in various Near Eastern civilizations – between historical experience and the structural development of theological systems is also well exemplified, alongside Vedic India, by early Greek culture, as attested by Mycenaean records, the Homeric and Hesiodic epics, inscriptions, and abundant archaeological evidence. In Aegean Greece, the transition from the Mycenaean era – marked by significant ‘Minoan’ influence – to the so-called ‘Greek Dark Ages’ witnessed the emergence of a divine hierarchy led by Zeus. The Mycenaean title wánax, formerly reserved for monarchs, was now extended to Zeus and a few other deities. Many older gods were marginalized or excluded from the pantheons of individual póleis.

A major crisis around the end of the second millennium BCE, recalled in Greek memory through the Homeric épos of the Trojan War and the nóstoi of the Achaean leaders, led to the disintegration of the Mycenaean kingdoms. From this turmoil emerged the revolutionary institution of the pólis. The Eastern-style absolute monarchy, upheld by sacred legitimacy and military elites (lawói), gave way – amid tensions – to aristocracies formed by noble family groups (génē). Councils of basilēes, representing these génē in the districts (dãmoi), became central to the new political order, with the lawói providing military defense.

Commerce and craftsmanship flourished once more, often under aristocratic direction, and Greek mariners rejoined the wider Mediterranean trade routes, extending into the Black Sea and the Atlantic. The divine order imagined in the Minoan-Mycenaean age, presiding from cloud-covered Mount Olympus, was replaced by a transcendent, stormless Uranian Olympus – unseen and unreachable by mortals.

This shift signaled a new relationship between humans and the divine. Anthropomorphic representations – emphasizing divine strength and at times insensitivity – prevailed over more abstract ones, bringing the gods closer to human experience while simultaneously asserting human superiority over other creatures. This reflected the ethos of the new political order, where citizens (polîtai) – equal in rights and duties – were governed not by a monarch ordained by the gods but by magistrates elected to uphold a nómos (law) mutually agreed upon by the citizenry. The principle of individual responsibility before both the pólis and its patron deities was thus established. The king’s dictates gave way to a moral code authorized by theologians from major sanctuaries.

The old familial solidarity, legally recognized, expanded into civic solidarity among fellow citizens, surpassing the boundaries of kinship and preparing the ground for later notions of universal human fraternity. A deeper religiosity emerged in those attuned to the moral transformation brought about by the development of civic consciousness. They sought to redefine the relationship between mortal beings and the vast, ever-changing yet eternal stage of phýsis, where human life was fleeting. For the most thoughtful individuals, this engendered a persistent reflection on the tension between life’s transience and the innate human yearning for permanence.

The most industrious póleis, deeply involved in Mediterranean trade – especially those along the Anatolian coast, the Aegean islands, the Attic-Boeotian peninsula, and the Isthmus of Corinth – were marked by a vibrant civic life. Within these city-states, internal power struggles among aristocratic elites and repeated attempts to impose oligarchic or tyrannical rule played a key role in accelerating the transition toward democratic constitutions. These, in turn, represented the natural culmination of any pólis that was culturally and economically dynamic, and thus inclined to experiment with alternative social and political forms. Somewhat different were the trajectories of the colonial póleis of the western Mediterranean, where flourishing overseas trade and industry were accompanied by specific internal tensions arising from the presence of indigenous populations. These tensions manifested both within the urban centers and their surrounding chṓra, and often, in more contentious terms, across the broader regional context. By contrast, the póleis of Asia – shaped by longer and more intense Greek settlement – faced fewer such frictions. In the western colonies, the influence of ancient noble lineages and traditional génē was weaker, thereby diminishing their capacity to obstruct institutional reforms or shifts in ideological and cultural orientations, as so frequently occurred in the motherland.

This historical landscape was shaped by ancestral traditions and cults, emerging political, economic, and religious forces, progressive aspirations alongside deep-seated resistance, and intense inter-pólis rivalries. In the western seas, fierce commercial competition – often leading to conflict between Greeks, Carthaginians, and Etruscans – added further tension. Within this complex setting, the reflective minds of Ionia sought to transcend the syncretic web of Aegean, Asiatic, and Egyptian cosmogonies and theogonies, intertwined myths and rites, and lingering traces of archaic superstition and shamanic practices. Their aim was to distill order and coherence from a vast accumulation of inherited representations and unexamined amalgamations. As in all human history, this movement of critical awakening in archaic Greece was initiated by poetic genius, inspired by an awareness of shared éthnos identity.

By the 8th century BCE, the long crisis following the fall of the Mycenaean monarchies had subsided, and new, authentically political institutions had taken root. The Greeks’ ancient ecumenical vocation drove explorers and merchants along the Mediterranean trade routes, while citizens from the póleis of the Aegean and Anatolia – above all the Ionians – migrated to southern Italy and Sicily. There, the lingering cultural memory of Mycenaean settlements (teíchea, empória) had predisposed native populations to enduring contact and coexistence with Hellenic newcomers. Typically, the autonomy of the Italiote and Siceliote póleis did not erode their genealogical and cultic bonds with their respective mētrópóleis, which, in turn, maintained close oversight of their colonies. Economic and political assistance flowed in both directions.

The colonists’ profound devotion to the shared civic legacy that underpinned Hellenic unity played a crucial role in the success of the colonial project in the West. The aristocrats who led these ventures had been deeply shaped by the spiritual wealth of the Homeric poems. In the Iliad, a celebration of Achaean victory over Asiatic forces – framed as an outcome of Hellenic solidarity that opened access to the Pontic and Caucasian regions – the Trojan War served as both a distant historical recollection and a poetic reimagining of the Mycenaean world. Its protagonists were elevated to heroic status, and its backdrop mirrored the sociopolitical life of Homer’s own time. This powerful memory of an epochal conflict, pervaded by a humanitas absent from the chronicles of the ancient Near East, found its counterpart in the Odyssey, which mythologized the daily trials of Greek mariners in the western seas – newly explored and thus apt settings for fabulous tales of men and daímones (as would later be the case for the eastern seas in the Thousand and One Nights).

Greek seafarers and traders, competing with their Levantine counterparts, resumed long-distance navigation to remote shores, retracing routes once plied by Minoan and Mycenaean vessels – depicted in the frescoes of Thera (modern Santorini) – and refined by generations of nautical observation and celestial navigation. The valor of Odysseus and his comrades differed little from that of Achaean and Trojan warriors: both were realistic embodiments of ideals, confronting enemies, natural forces, divine wrath, and human passions with equal resolve – and at times, mastering them.

The dread vision of murky Hades did not eclipse the luminous ideal of adventure undertaken per virtùte e canoscenza, nor did it stifle faith in mētis, the cunning intelligence presided over by Athena. Homer’s heroes became exemplars for the aristocracies of Ionia before being embraced by all Greeks. The figure of Odysseus – ever willing to surpass conventional boundaries – foreshadowed the early seekers of truth: those unsatisfied by mythical explanations of nature, humankind, and the divine, and eager instead to engage their own faculties – ópsis (vision), akoḗ (hearing), lógos (reasoned discourse), mnḗmē (memory), and noús (intellect) – in the pursuit of understanding.

A nascent, though not yet critical, need for cognitive understanding is already evident in the Theogony, a poem composed by Hesiod at a time not far removed from that of the Odyssey. With ethical and didactic intent, Hesiod crafted a ‘sacred history’ that drew – according to his own account, veiled by the revelations of the Muses of Helicon – from hymns and poetic legends, witnesses of ancient religiosity, and traditions preserved in sanctuaries. Much like earlier texts from the ancient Near East, the Hesiodic work interweaves myths concerning successive generations of gods with cosmogonic narratives. These myths poetically transfigure centuries of natural observations and mark the beginning of a ‘historicization’ of phýsis.

The poet, likely born in Ascra in Boeotia – a region where northern Greek invaders had imposed their ethnic identity over earlier Ionian and Aeolian inhabitants who largely migrated to the islands and Anatolian shores of the northern Aegean – probably had access to hieroì lógoi, sacred narratives not only from Hellenic sanctuaries but also from Anellenic Anatolia and possibly even from Mesopotamia via Anatolia. By the time Hesiod composed his poem, the Olympian pantheon had already been established for several centuries. Yet, memories of older religious forms persisted, and pre-Olympian cults not included in the dōdekátheon (the twelve Olympians) still retained devotees and, in some póleis, remained part of public religious practice.

Hesiod was thus able to reach back beyond the formation of the Olympian order and rescue from oblivion older myths and early theological and cosmogonic speculations: the birth of Érebos and Black Night from Cháos (the Void); Earth’s union with her son, the Starry Sky (Ouranós); his castration by their son Kronos ‘of twisted cunning’; Kronos’ marriage to his sister Rhéa; and, finally, the birth of Zeus, ‘father of gods and men’, who would become ruler of the Olympian pantheon and embodiment of the luminous sky. The succession of divine dynasties recounted in the poem seems to mirror the historical phases of Greek religion up to the Olympian system, probably canonized by the priests of Pythṓ (Delphi), whose authority in ritual regulation was acknowledged by all Greeks.

The relationship between Hesiod’s cosmogonic-theogonic myth and the mythologies of the ancient Near East – well documented in Mesopotamian and Anatolian sources – is unmistakable. Most notable among these is the Hurrian myth of Kumarbi, known in a Hittite version from the archive-library of Khattusha, the Hittite capital. It narrates how Anu, god of the sky, was castrated by Kumarbi, who was in turn dethroned after attempting to defeat the storm god, the chief deity of the Hurrian pantheon. The undeniable influence of Hurrian-Hittite and Sumerian-Akkadian myths on Greek myth-making must date to a time before the collapse of the Mycenaean monarchies. Such external influence could only have been effective while these absolute monarchies still prevailed, when dynastic priorities could outweigh resistance to foreign religious elements – unlike the later póleis, whose political institutions, rooted in noble clans (áristoi, or optimates), were tightly bound to traditional cults. These clans derived cohesion and authority from their association with specific shrines and sacred practices, which they zealously preserved from foreign contamination.

That Mycenaean religious centers – under the unchallenged authority of wánaktes (monarchs) – placed virtually no barriers to the adoption of eastern myths is understandable given the intensity of both diplomatic and commercial exchanges with the Near East. A particularly telling episode concerns the temporary translation of the cult statues of two non-Asian deities – associated with major Achaean shrines in Akhkhiyawa (likely Ialysos in Rhodes) and Lazpa (Lesbos) – to Khattusha during the reign of King Mursili II (ca. 1330–1310 BCE). Stricken with aphasia believed to be divine punishment for a sacrilege committed by his predecessor Shuppiluliuma, Mursili II sought healing through the miraculous intervention of these foreign gods after appeals to the native ‘thousand gods of the land of Khatti’ had failed. A similar gesture had occurred roughly fifty years earlier, when the Mitanni king Tushratta sent a statue of Ishtar of Nineveh to Egypt to cure the ailing Pharaoh Amenhotep III, who had previously experienced the goddess’s efficacy thanks to a prior gift from Tushratta’s father, Shuttarna II.

It is thus highly plausible that in the many Greek sanctuaries of Asia – ranging from Klaros to Ephesus, Didyma to Labranda, and in the islands of Lesbos, Samos, and Rhodes – the religious life of the Mycenaean age was not immune to the influence of Near Eastern religiosity. The cosmogonies and theogonies elaborated by local priests likely did not ignore Anatolian, Mesopotamian, and Syrian mythologies, which were themselves enriched by the doctrines of Babylonian astronomers. Indeed, the Greeks have always displayed a characteristic openness toward the cultures with which they came into contact. Their intellectual disposition has consistently allowed them not only to assimilate but also to rework, with creative autonomy, those elements that piqued their interest.

In the Near East, shifts from traditional cosmogonies and their associated theologies to reflections on the human condition – his place in the cosmos and his destiny – were extremely rare. When they did occur, they were never accompanied by open critiques of the theological systems maintained by the major priestly colleges. Even the famous clash between Amenhotep IV (Akhenaten) and the Theban priesthood of Amun remained within the sphere of religious belief and ritual. Although a new vision of humanity emerged in art, it did not evolve into a framework of free or critical thought. Within the great civilizations of the ancient East, neither the emergence of proto-scientific inquiry nor its technical achievements ever came into conflict with religious authorities or interfered with priestly cosmological and theological speculation. Even astronomy – highly esteemed in Babylonian science – remained a specialized discipline with limited conceptual impact beyond its technical applications.

Such disengagement was, in large part, a consequence of the institutional framework: schools and libraries were tightly integrated with centers of royal and sacerdotal power, and the same held true in Egypt. This structural dependency ensured that scientific pursuits retained a predominantly empirical and classificatory character, subordinate to utilitarian goals, and reinforced the pre-eminence of technology over theoretical exploration.

In contrast, Archaic Greece had by then undergone a profound religious transformation from the earlier Minoan and Mycenaean phases, where state organization culminated in the authority of a ruler sanctified by priestly endorsement and who, in turn, served as the protector of religious institutions. Though the pólis was likewise founded on sacred principles, observance of ancestral rites and state-sanctioned cults – aligned, though not always identical, with the canonical dōdekátheon – no longer depended on the dictates of a monarch or on the mediation of a hierophant. Just as noble clans (génē) were free to preserve the worship of ancestral deities or progenitors in traditional forms, so too was each polítēs granted the liberty to express eusébeia (Lat. pietas) in the ways he deemed most worthy.

Only those who conspicuously displayed asébeia (impietas) or flouted the moral principles that underpinned civic harmony – and around which public sentiment coalesced – risked civil exclusion. This extraordinary freedom – though limited in practice by popular ignorance or political enmity, as the fates of Pythagoras, Anaxagoras, and especially Socrates illustrate – not only encouraged scientific inquiry but also deepened personal religiosity. In fact, religious sentiment was a vital and inextricable element of Greek artistic creation, literary expression, and scientific pursuit.

A comparable disposition may be found in ancient Indian culture, where poets, sages, and artists – like their Greek counterparts – transcended the tendency to anthropomorphize the divine in accord with mutable natural and human phenomena. Instead, they elaborated, in tacit opposition to polytheism, the concept of a supreme and omnipotent creative deity – likely during a phase in which the Indo-Aryan peoples were still culturally united, as Zoroastrian doctrine similarly suggests.

In both traditions, concepts, emotions, and mental states were deified. Already in Homer one finds Átē (Folly), and in Hesiod’s Theogony appear Éris (Strife), Oizýs (Anguish), the Moîrai (Fates), Némesis, Apátē (Deceit), Philótēs (Affection), and Gêras (Old Age). In the Vedic pantheon, Aditi (Infinity) becomes the mother of the seven Āditya, among whom are Varuṇa (the starry sky), Bhaga (equivalent to Agathḗ Týchē), Aryaman (akin to Moîra), and Dákṣa (corresponding to Mētis). What appears as an exuberant polytheism actually set the stage for its dissolution by fragmenting the coherence of divine personalities and human personhood alike, thus catalyzing a movement toward the conception of divine unity.

In the Greek world, the lived experience within the pólis – a product of a liberal ethos – revitalized this trend and projected it into the political sphere. The sense of personal responsibility, once exercised before the wánax, custodian of the thémistes, now found expression in civic terms: observance of self-legislated laws, solidarity with fellow citizens, and respect for public religion became the moral tenets of polítēs life.

Within this context reemerged figures reminiscent of ancient seers: intermediaries and interpreters of divine will, visionaries whose knowledge was matched by ascetic lifestyles, poetic eloquence, and the serene demeanor of those who know what most ignore. The myth of the ‘noble savage’ – such as the Hippḗmolgoi (‘milk-feeders’) and the Ábioi, ‘most just of men’ (Iliad XIII, 5 ff.) from the foggy northern lands, whose shamanic rites had influenced Apollonian temples – gave way to the image of the mánteis, a prophet graced with divine insight and endowed with thaumaturgic power.

The paradigmatic figure of this transformation is Orpheus: poet and musician, enchanter of humans and beasts, and proponent of a moral code that promised the soul, freed from Hades’ gloom, an eternal abode beside the gods. In this vision, knowledge united with pietas and ethical discipline, and offered Greeks the hope of salvation. This ideal owed much to the priests of Apollo, from their oracular centers in Greece and Asia Minor and ultimately from Delphi, where the temple of the Uranian deity was superimposed on the archaic oracle of Gaia or Thémis. In its foundations lay the tomb of the Cretan Dionysus – a vestige of the pre-Olympian religion in which divinities underwent cyclical death and rebirth.

Between the 7th and 6th centuries BCE, the Greeks underwent a critical turning point in the evolution of their intellectual life. This transformation unfolded between two symbolic poles: Crete and the Ionian world, including both Asia Minor and Athens. Crete, renowned for its archaic mystery cults, cathartic rituals, and especially for an eschatological tradition linked to the figure of Minos – mythical in religious lore but anchored in the historical consciousness of the Greeks – came to embody a past saturated with divine presence. The Ionian world, by contrast, heralded a new era defined by keen observation of political reality, a reverent regard for national traditions, and an expanding appetite for experience and knowledge.

Emblematic of this crisis were the events surrounding Cylon’s attempted coup in Athens. The son-in-law of the tyrant of Megara – a city steeped in Mycenaean heritage and a commercial rival of Athens – Cylon sought to impose tyranny. The massacre of his followers in a sacred precinct, ordered by the archon Megacles of the Alcmaeonid génos, provoked political backlash. The Alcmaeonids, accused of sacrilege, were permanently exiled along with Cylon himself. In the wake of the sacrilege, the city invited the Cretan mántis Epimenides to perform a ritual purification. Epimenides, an expert in retrospective divination – recognizing in past events portents of future calamities – did not leave a lasting imprint on Athenian politics. The resolution to the crisis came instead with Solon’s reforms, which signaled the rise of a new spirit among the most active segment of the gnṓrimoi (notables), who pursued commerce not merely for profit, but also from an intellectual drive to understand the world.

Athens cultivated particularly strong ties with Miletus, the most dynamic pólis in Asia. Miletus’s rivalry with Megara for dominance over trade routes in the Euxine Sea indirectly benefited Athenian interests. During the late 7th and early 6th centuries, Miletus supported Athens in securing control over Sigeum, a strategic site at the entrance to the Hellespont previously fortified by the Lesbians. These trade routes facilitated cultural exchange, and Athenian statesmen – beginning with Solon – understood the significance of commerce for both domestic governance and foreign policy.

In the 6th century, Pisistratus, aware of the symbolic weight of Delos as the Ionian religious center and home to an Apollonian oracle eclipsed by Delphi’s rising prestige, took measures to ‘purify’ the island. He reinvigorated the Panionian festival and, recognizing the national importance of the Homeric epics, promoted a critical recension and their recitation during the Panathenaic festivals, thereby asserting Athens’s cultural primacy among the Ionian póleis.

While Solon’s reforms and Pisistratus’s initiatives elevated Athens’s stature, Ionia – particularly Miletus – flourished not only in commerce but also in literary and scientific achievement. Frequent interaction with the peoples of Anatolia, especially Lydia, and the diffusion of Hellenic culture into major Anatolian centers stimulated both curiosity and unease among the Ionian aristocracy. It was among them that a critical spirit flourished, fueled by the political transformations of the age and giving rise to an unmatched intellectual vitality.

Faced with the parallels between Eastern cosmogonies and those rooted in their own tradition, Greek thinkers increasingly sought rational and experiential answers to metaphysical questions. The conceptual relocation of the Olympian gods from Mount Olympus to the celestial sphere marked an effort to integrate human existence within the vastness of aithḗr, the ‘deepest ocean’ of space – a sign of the Greek longing to discover the eternal amid the transient. From celestial contemplation, Greek philosophy and science derived renewed direction. Whereas in the East, star observation primarily served navigation, agriculture, or state cults, in Miletus – with Thales, Anaximander, and Anaximenes – it became the cornerstone of cosmological inquiry.

The Earth was now studied not merely in terms of its benefit or harm to humans, but as the central component of a cosmic system. Inquiry thus shifted toward understanding the structure and composition of the visible universe and identifying its archaí, the fundamental principles of reality. The cosmogonic framework underwent a profound transformation: the gods, though not excluded, assumed an auxiliary or inscrutable role. Intellectual attention focused on what they had created – or what had pre-existed and might be reformulated through them.

Nevertheless, belief in divine involvement in the formation and order of the cosmos, in natural phenomena both regular and exceptional, and in human fate remained deeply ingrained. This religiosity, distinct from adherence to génos, éthnos, or pólis traditions, was ever-present in Greek art, literature, and science. Public worship of the ancestral gods of each pólis was carefully preserved, even as changing views of the divine sometimes led to detachment or even irreverence – witness the mockery of the gods in Aristophanes’ comedies.

As the civic religion declined, authentic religiosity revived in new forms, manifesting as pístis, a hopeful confidence in an afterlife as promised by the mystery cults. These ancient rites held special appeal: the Eleusinian mysteries of Demeter – particularly influential in Attica – and the Dionysian mysteries, which spread across Greece and Magna Graecia, had deep roots in Crete.

While individual citizens navigated between traditional cults and eschatological myths, the póleis themselves remained guardians of sacred heritage. They maintained a formal ritual practice: the chrāstḗria, consultations with the divine in designated sanctuaries. These did not merely predict future events but offered divinely inspired guidance on specific civic or moral dilemmas.

The variety of oracular institutions reflects their shared origin in the Earth, the abode of the dead and source of primal physical forces. The sacred history of the most illustrious oracle – that of Pythó (Delphi) – exemplifies the transition of the pantheon from chthonic to Uranian focus. Apollo, a solar deity, violently seized the oracle from Gaia or Themis, but its original character persisted. From a natural cleft in the earth (chásma gḗs), vapors arose that intoxicated the prophetess, a Sibyl of Anatolian type, whose ecstatic utterances were rendered comprehensible by interpreters (exēgētaí).

Politically supported by the Amphictyony of Anthela near Thermopylae, the Delphic sanctuary outshone all others, from the ancient oracle of Zeus at Dodona to the Apollonian shrines in Delos, Boeotia, and Asia Minor. The Delphic priests proved shrewd administrators of divine authority, and the ethical code they developed in dialogue with the doctrines and comportment of renowned sophoí did not disregard the evolving currents of moral and political thought emerging across the Greek world, in both colonies and mother cities.

The figures of the ‘Seven Sages’ (Hepta Sophoí) came to replace the vátes and seers through whom, during the Hellenic ‘Middle Ages,’ the Greeks had expressed their longing to transcend the human condition and to partake in the serene and eternal life of the gods. Whereas the heroes and truth-teachers of the post-Mycenaean era – some boasting divine ancestry – had once dominated the cultural imagination, they were now succeeded by men distinguished not by mythic lineage but by dynastic authority or life experience. These sages no longer spoke in ambiguous prophecies or veiled admonitions, but formulated moral precepts and practical advice, inspired by those ágraphoi nómoi (‘unwritten laws’) that embodied the Greek éthos, the ideal moral heritage of the Hellenic people. Their counsel was often rendered in gnomic form – concise, imperative maxims that conveyed timeless wisdom with rhetorical force.

As it passed into classical tradition, the legend of the Seven Sages retained the sacred character implied by the Apollonian number seven, explicitly linked to the shrine at Delphi. The priests of the Pythian oracle – more attuned than those of other Apollonian centers to the evolving needs of a society undergoing profound transformation – recognized that this practical wisdom reflected the convergence of ancient traditions with the growing mercantile and colonial ambitions of a wider class of citizens. In the sphere of religious life, hereditary priesthoods tied to noble lineages were increasingly replaced by elected priests, while aristocrats and gnṓrimoi now shared influence with artisans and merchants in both civic life and religious practice.

According to Pausanias (Periegesis, X.24), two maxims – “Know thyself” (gnṓthi seautón) and “Nothing in excess” (mēdén ágan) – were inscribed in the prónaos of the Delphic temple and attributed to the Seven. Pausanias lists among them Thales of Miletus and Bias of Priene (Ionia), Pittacus of Mytilene (Aeolis), Cleobulus of Lindos (Doris), Solon of Athens, Chilon of Sparta, and – instead of the Corinthian tyrant Periander – Plato names Mison of Chen (Thessaly) in the Protagoras (343a), a version considered among the oldest. Other traditions offered alternative figures: Epimenides of Crete, Cleophas of Lebedus, Pythagoras, and even the Scythian sage Anacharsis.

What remains essential is the attribution of exceptional sophía to men well-versed in political life and aware of the enduring value of those unwritten laws that upheld veneration of the gods, observance of civic law, respect for ancestors, and human solidarity. This marked the threshold of a decisive phase in classical history, when the traditional wisdom of the sophoí no longer sufficed to meet the increasingly urgent thirst for knowledge. Greeks, encountering a multiplicity of cultures, began to reframe old questions – about nature, the divine, and humanity – in new, rational terms suited to the expanding horizons of their world.

It was no longer technical challenges that most captivated them, but the vast natural stage on which life unfolded. Those inclined to observe the patterns and rhythms of Earth and sky were stirred to reflections that transcended mere utility in agriculture, trade, or craft. The myths handed down from the ancestors no longer satisfied; divine images had receded before anthropomorphic ones, and traditional explanations were increasingly rejected. The historéēn – inquiry driven by its own internal momentum – emerged as the new method of seeking truth.

From this impulse arose a new term: philósophos, denoting one who recognizes that sophía is neither a gift of the gods nor a privilege of demonic beings, but the end (télos) of a lifelong endeavor of the human intellect. Implied in this was the foreboding that no understanding could be definitive, for one question invariably begets another. The answers to fundamental inquiries – about human nature, existence, the soul, the cosmos, and its archaí – were now sought in the manifold expressions of phýsis, in the vital energy perceived in thought and action, and in the inner depths of the psychḗ and ultimately the noús.

Within a few generations, the Greek world underwent an intellectual revolution without precedent in the Mediterranean. In the 6th century BCE, the institutions and religious traditions of the pólis remained largely intact, even amid power struggles. But scientific research boldly pursued new directions, unhindered by the theologians of major sanctuaries or by state cults. The former, unlike their Eastern counterparts tied to monarchic authority, had developed autonomous ritual systems and lacked both motive and means to oppose philosophical speculation. The latter, concerned with overseeing rites and maintaining public reverence for the ancestral éthos, had little to do with the life of the mind. Philosophers, for their part, always moved within the bounds of a deeply religious culture.

Tradition credits Pythagoras with coining the term philosophía; he was revered not merely as a thinker but as a sanctified figure. No one better exemplified the transition from the politically engaged sophoí to the research-oriented philósophoi. The Akragantine philosopher Empedocles thus portrayed Pythagoras as an ideal sage and discoverer: “a man of rare wisdom, who possessed the widest breadth of soul and was supremely skilled in all kinds of works and wisdom” (DK 31 B 129).

Among the Ionian thinkers, Thales of Miletus had already stood out. A member, like Herodotus, of a Hellenocarian family, he may have been the first to shift the focus of speculation from inherited cosmogonies and their divine actors to the visible phýsis, especially the starry heavens and their orderly movements – regulated, as he believed, by a rational mind. This marked the beginning of a search for archaí, the fundamental principles behind the manifold phenomena of the universe, or for a single archḗ, the unifying force of all.

This quest signaled a new forma mentis, a mentality liberated from traditional myths and practical constraints, animated instead by a desire for truth for its own sake. Such a forma mentis could only arise in the intellectual climate of the pólis, a creation of free citizens conscious of their role in shaping the world around them. Alongside inherited ethical values, pístis (faith in truth) and elpís (hope of transcending human limits, as expressed in the Delphic maxim gnṓthi seautón, nosce te ipsum) became vivid forces.

These attitudes – present in every genuine intellectual pursuit – are expressions of historical consciousness and of the noús’s creative potential. As the chorus of Sophocles’ Antigone (vv. 332–333) declares: “Many are the wonders, and none more wonderful than man.” Animated by this awareness, Pythagoras, a Samian aristocrat steeped in Cretan and Pythian religious traditions and well-informed in Eastern knowledge, left his tyrant-ruled homeland to found the first philosophical school in Magna Graecia, at Croton – a city where Samian merchants had partners, just as Milesians had in Sybaris.

The Pythagorean school was an unprecedented institution: both a community of initiates and a scholarly society. It likely served as a model for other professional associations that either assumed the form of génä or coalesced around a real génos claiming descent from a deity. Such were the Asklapiádai – physician lineages in Cos, Rhodes, and Cnidus – and the Ouliádai of Velia in Italy, devoted to Apollo Oúlios, the healer.

Pythagoras reinforced Croton’s cultural and religious ties to Delphi, as evidenced by the Pythian tripod depicted on Crotonian staters from the 6th and 5th centuries BCE. The priests of Delphi, closely connected with the Amphictyony of Anthela, did not remain indifferent to the crises and transformations that marked the rise of the great póleis, both in the Greek mainland and in the colonies. In the western settlements – where the influence of ancestral religious traditions and noble lineages was less binding than in the metropolis – the intellectual climate was more favorable to speculative innovation. This openness proved decisive for the future of scientific inquiry, as Magna Graecia became a fertile ground for schools of thought and medicine rooted in Ionian speculation: foremost among these were the traditions founded by Pythagoras, Alcmaeon, and Parmenides.

Pythagoras initially drew inspiration from the doctrines of the Ionian physiológoi: the idea of hìlä (matter) as a living, developing entity (zõon), the ápeiron (the infinite) posited by Anaximander as the archḗ – the originating principle – of all beings (DK 12 B 1), and the perceived contrast between the primordial cháos of the ápeiron and the orderly world revealed through naturalistic investigation, especially in astronomy. This latter discipline revealed regularities expressible through geometric forms and thus, numerically. Less focused on cháos than on kósmos (a term attributed to him), Pythagoras expressed both the order and beauty of the universe through this concept. His belief in the unity of the universe amidst the multiplicity of forms aligned with the doctrine of the transmigration of souls (metempsìchüsis) – perhaps a continuation of pre-Olympian theological motifs, such as the cyclic death and rebirth of deities like Dionysus and Zeus.

The opposition between kósmos and cháos also mirrored the philosophical duality of the finite and the infinite, laying the groundwork for the theory of opposing archaí (DK 58 B 5). The notion of the péras (limit) naturally introduced the problem of the ápeiron (unlimited), entwined with religious reflections on the dichotomy between the mortal and the divine. When confronted with the inadequacy of conceptual language to grasp the unknowable, numbers (arithmoí) – infinite in succession – appeared as suitable symbols for the fundamental elements and forces of the universe. The Pythagorean vision of cosmic unity and harmony, supported by the predictable motions of celestial bodies, found further analogues in the search for what the Hippocratic treatise Ancient Medicine calls “heavenly and subterranean things” – that is, those inaccessible to direct observation, as also stated by Alcmaeon (DK 24 B 1): “Of the invisible, of that which pertains to the dead, only the gods possess knowledge.”

In this remarkable Pythagorean dawn of science, the empirical observation of particulars (tà hékasta), logical reasoning, and intuitive insight – guided by a keen sense of the divine – interacted synergistically. This intellectual discipline, informed by a venerable ethical tradition, shaped the vocation to inquiry. The pythagorikòs bíos (Pythagorean way of life) likely did not differ from the orphikòs bíos, a way of life grounded in Orphism – a mystery religion that emphasized not so much devotion to chthonic deities, but rather a faith centered on Mnämosýnē, the deified Memory.

Because of its distinct character, Pythagorean spirituality deeply influenced the main currents of Greek thought. The philosophical education of Parmenides, founder of the Eleatic school, was already shaped by Pythagorean doctrines. In contrast to the dóxai (opinions) of mortals, Parmenides opposed a truth (alétheia) perfect in its completeness, ‘round’ like the circle and the sphere, accessible only through intuition presented in the form of a mýthos – a revelatory discourse of a goddess. Through this path, the intellect ascends along a hierà hodós (‘Sacred Way’), an itinerarium mentis reminiscent of the mystical journey opened by Mnämosýnē to the Orphic bákchoi – a sequence of symbolic images in which the recognition of human limits and the aspiration to transcend them are implicitly encoded.

Since Pythagoras, the tension between two imperatives of the noús – to expand knowledge and to search within anámnäsis (recollection) for orientation in the face of the ágnüston (the unknown) – has never ceased to drive philosophical inquiry wherever Hellänikḗ phōnḗ, the idiom of Greek thought, has echoed. This orientation, which some modern scholars lament for having inhibited the development of ‘applied’ science in Greece, was in fact decisive in shaping a vision of scientific research whose impact has endured from the time of Nicholas of Cusa, through Bruno and Galileo, to the present day.

Giovanni Pugliese Carratelli

While it is legitimate to speak of science in relation to the Greeks and Romans, the Etruscan civilization, by contrast, is characterized by an approach to the observation of phenomena that is not merely prescientific, but in fact antithetical to the scientific spirit. This approach is marked by a ritualistic obsession permeating every aspect and moment of life and knowledge, and by an all-encompassing religiosity that effectively transforms religious ideology into a form of pseudoscience.

This was already recognized in antiquity: the Etruscans were famously described as “a people above all others devoted to religious practices” (Ab urbe condita, V, 1, 6), and Isidore of Seville offered the paretymology of their name, Tusci, from the Greek thysiázein (‘to sacrifice’) (Etymologiae, IX, 2, 86). The clearest and most complete definition of the Etruscan pseudoscientific mentality is provided by Seneca, who, in a well-known passage, observes: “This is the difference between us and the Etruscans [...]: we believe that lightning is produced by the collision of clouds; they, by contrast, believe that clouds collide in order for lightning to be produced. For they, attributing everything to the divine, are convinced that things are not meaningful because they occur, but rather that they occur because they are meaningful” (Naturales quaestiones, II, 32, 2).

This passage illustrates in stark terms the opposition between Greek naturalistic speculation (represented by Seneca’s ‘we’) and the theological-teleological worldview of the Etruscans. The Roman world was familiar with this worldview due to centuries of close contact and, above all, the longstanding Roman practice of consulting Etruscan haruspices in cases of prodigia, ostenta, and portenta – extraordinary natural events which defied rational explanation and were interpreted as signs of a disturbed pax deorum, to be restored through specific rituals prescribed by the haruspices.

Etruscan scientific experience appears deeply conditioned by a magico-religious system developed over many centuries. This system was organized around a cosmology based on a meticulous web of homologies and correspondences, whereby deities with distinct functions, powers, and attributes governed the visible world. The history of Etruscan science reflects the practical and technological implications of this worldview. Archaeological evidence reveals substantial achievements in various fields of knowledge – such as astronomy, meteorology, and hydraulics – attesting to a high level of empirical observation developed in the context of divinatory practices and transmitted through the priestly colleges of augurs and haruspices.

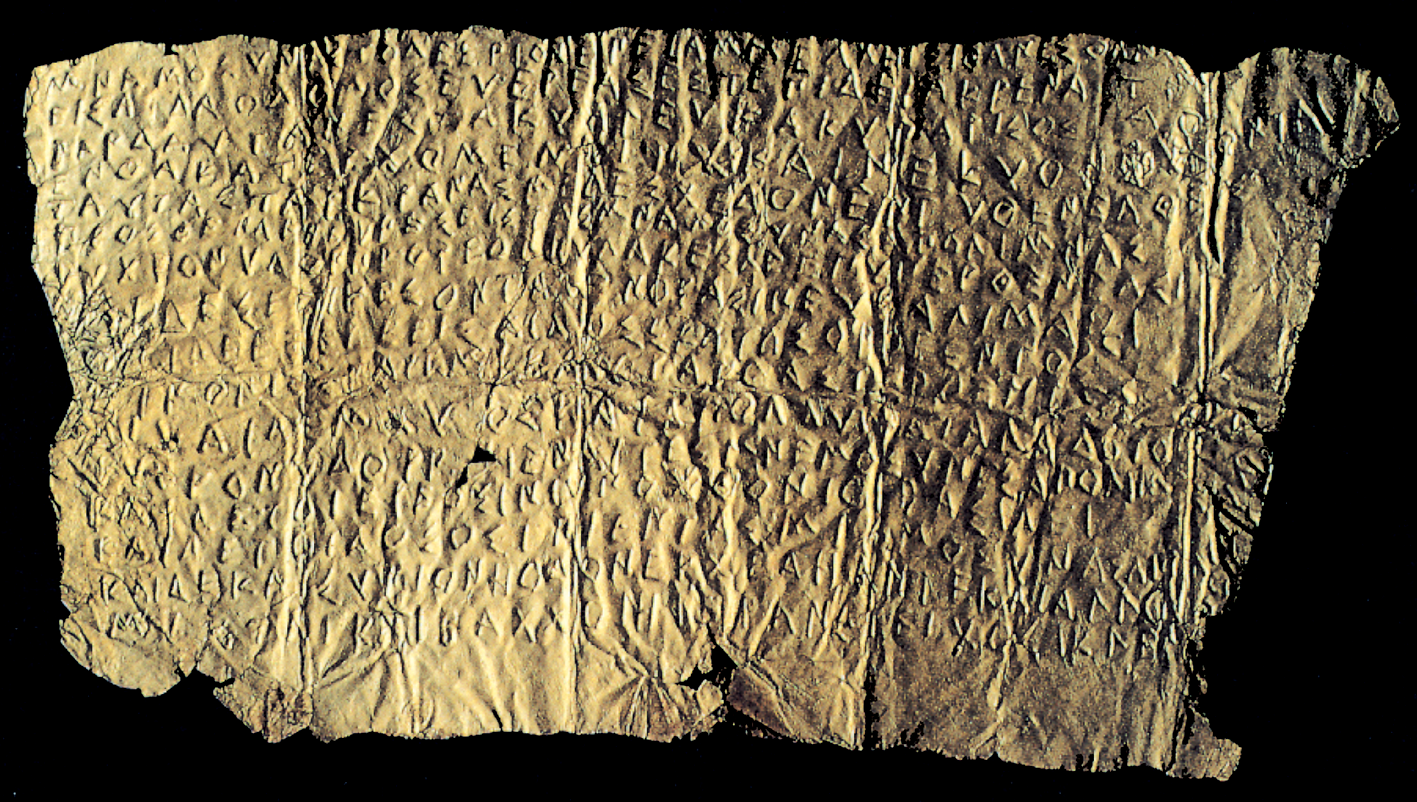

Nevertheless, regarding this doctrinal corpus – Etrusca disciplina, as the body of writings encompassing all Etruscan knowledge was known – our sources are limited. Direct sources are extremely rare and fragmentary; indirect sources are more abundant but often uncertain or subject to debate. Among the direct sources, in addition to the few surviving ritual texts (such as the ceremonial calendars of the Liber Linteus of Zagreb and the Tabula Capuana – important yet controversial due to their composition in the Etruscan language), we include classical Latin and Greek texts which preserve, via a broad and often obscure minor literature (ranging from gromatic to astrological treatises), the translation and reinterpretation of original Etruscan concepts.

Indirect sources derive from archaeological and antiquarian analysis of material culture and religious iconography, both of which were profoundly Hellenized from the earliest phases of contact with the Greek world, often obscuring access to the underlying structures of native thought. As a result, the reconstruction of many categories of Etruscan thought remains fraught with fundamental uncertainties and unresolved questions.

Among the most significant aspects of Etruscan religion attested in our documentation is the highly ritualized character of cultic practice and, by extension, of the relationship between the human and divine realms. Both indirect literary sources and those intelligible elements of the direct sources emphasize the precision of religious acts – whether in the observation of natural or social phenomena (which constitutes the foundation of haruspical practice), or in the exact execution of the sacred procedures outlined in the ritual calendars (Liber Linteus, Tabula Capuana) and in the prescriptions concerning procuratio, portenta, and ostenta. These prescriptions prescribed the “remedies” offered by priestly tradition to counteract the divine displeasure manifested through prodigies or celestial signs such as lightning and thunder. The guarantee of pax deorum – the harmonious relationship between the natural and supernatural orders – relied on both the scrupulous analysis of the sensible world and the observance of ritual norms, tasks entrusted to the priesthood.

This system presupposed a theology which, though sharing broad features with other ancient Mediterranean religions, was distinguished by its pronounced emphasis on divine inscrutability. Particularly notable in this regard is the presence in the Etruscan pantheon of deities described as involuti – ‘inscrutable’ – or even opertanei, ‘hidden’ or ‘secret’ gods.

Ambiguity in the forces governing the world and the inexplicability of the divine are defining features of Etruria’s religious ideology, which has a dual root in the historical and social fabric of the region. On one hand, it reflects archaic magico-religious conceptions, fundamentally at odds with any rational, secular, or scientific approach to reality; on the other, it presupposes a social relationship between a dominant class and a subjugated populace. This situation not only inhibits the development of ideology along rational lines, but also enables the dominant class – exclusively comprising the priesthood, intermediaries between these hidden divine wills and the world – to exercise complete control over the dominated. Consequently, the undeniable archaism of Etruscan belief systems mirrors a corresponding social archaism, perpetuated in part by the enduring monopoly of hegemonic groups over religious knowledge and its instruments. The agrarian character of many aspects of Etruscan religion is closely linked to this persistence.

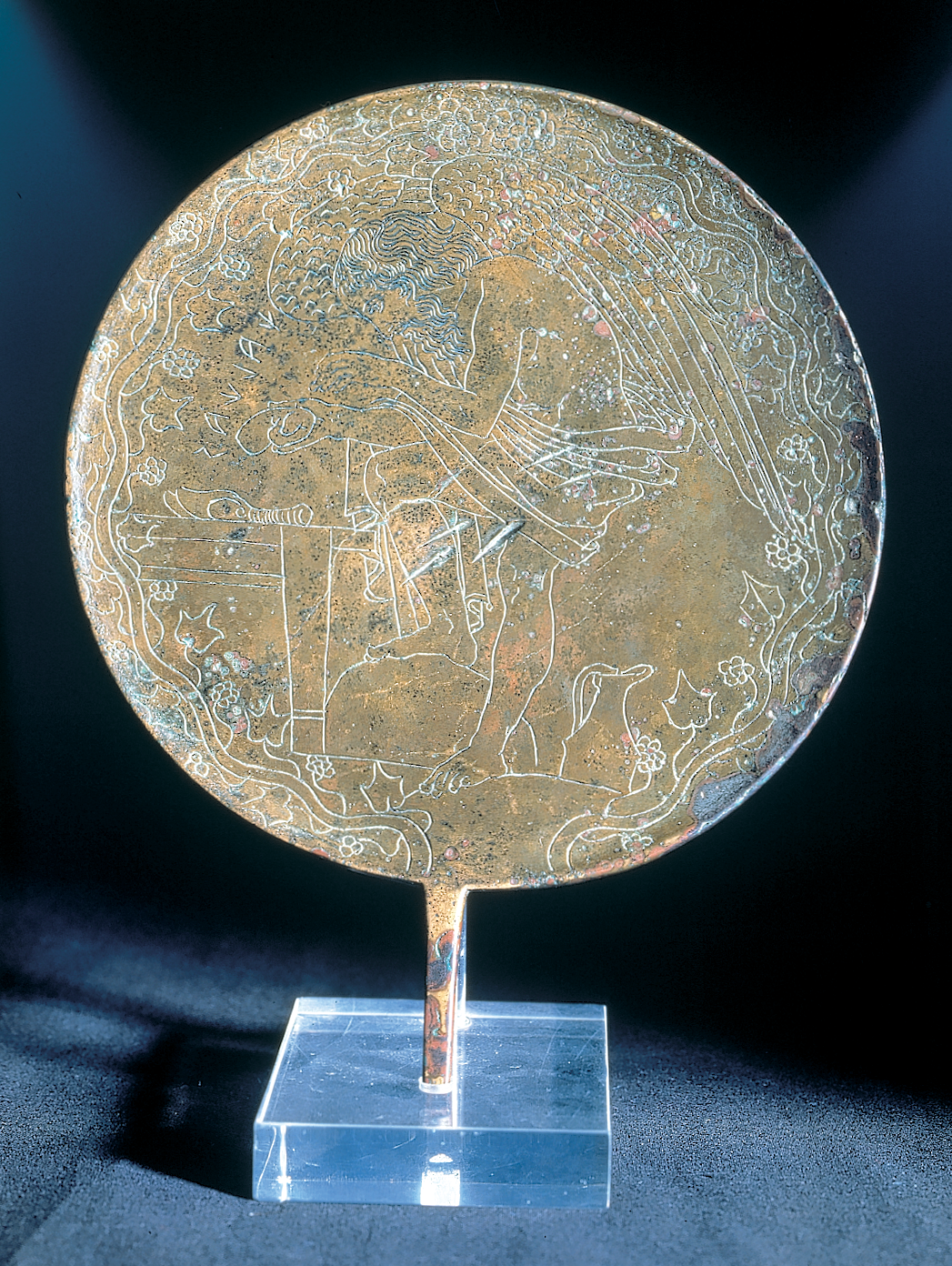

In this context, the presence within the minor pantheon – only superficially concealed by the general patina of Hellenization – of deities associated with generative powers is particularly telling. These include a number of female figures bearing names of unmistakably local origin, known primarily through iconographic evidence. They appear to preside over erotic and reproductive functions, paralleling figures referenced in the disciplina (known via translations) under the names of Genii and Favores. These entities reflect a very ancient historical context in which reproductive capacity held central importance, corresponding to a social structure based on kinship systems in which generation and fertility were of primary concern.

Equally archaic is the structure of core religious thought, which posits precise correspondences between celestial, terrestrial, and chthonic realms – each inhabited by homologous divine entities, marked by analogous natural phenomena, and defined by spatial dichotomies of positive and negative valence. These cosmic correspondences form the basis of a doctrinal framework that privileges magical connections between the sensible and supersensible worlds. Such principles are central to the analytical and interventional practices of the haruspices within the Etruscan disciplina. Human, natural, animal, and vegetal domains are interconnected through sympathetic relations that enable the parallel interpretation of phenomena as a means to decipher the obscure will of the gods and to transfer meaning from one sphere to another. In this way, a divine ‘sign’ manifested within one system may be interpreted through another and expiated by acting upon a third.

For example, a thunderbolt – a sign that belongs primarily, though not exclusively, to the celestial sphere – may strike a statue, an object from the human realm. This event can be expiated through the sacrifice of an animal from the animal world, consecrated to the underworld, provided there is a ‘qualitative’ correspondence among the sign, the object struck, and the physical or symbolic attributes of the sacrificial victim and the associated ritual.

This primitive yet sophisticated system of cosmic symmetries, like the earliest layers of the Etruscan pantheon, was by no means closed to influences from other cultures. It absorbed augmentations and additions from various philosophical and religious systems, most prominently from the Greek world, but also from other traditions of diverse origin and increasing complexity. Thus, the disciplina underwent a process of accretion over time: anthropomorphic and mythological elements of Eastern and Greek provenance during the Archaic period; Dionysian and Orphic-Pythagorean currents during the Classical period; and astrological and mystery doctrines during the Hellenistic period. These influences progressively modified and expanded the original ideological framework in ways that are not always easy to disentangle.

Nonetheless, this process of integration enabled the Etruscan priestly elites not only to maintain firm control over profound ideological transformations and to safeguard the existing social structure, but also to retain exclusive authority over all forms of knowledge – including technical and scientific domains – and any potential innovations that such knowledge might engender. The success of this integrative process is evidenced by the popularity attained by haruspical doctrines in Rome during the Late Republic, where they survived the decline of Etruscan national society and culture and were incorporated into a broader cultural milieu steeped in theosophical and astrological-mystical speculation.

Documentation on Etruscan civilization prior to approximately 630 BCE – i.e., before the onset of the phase conventionally referred to as the Recent Orientalizing period – relies almost exclusively on necropoleis, with only minimal information deriving from settlement sites. These latter, if more extensively known, might offer a broader understanding of local ritual practices and belief systems. Consequently, our knowledge encompasses only a partial view of the religious ideology and corresponding worldview of the time. Nevertheless, certain elements of Etruscan thought can be traced back to this earliest and most archaic historical phase.

In particular, prestigious bronze artifacts – such as a cinerary lid and a wheeled stand (possibly a forerunner of the historical praefericulum) – discovered in the tombs of the Bisenzio necropolis, a settlement located on the western shore of Lake Bolsena, suggest that early Etruscan religion envisioned deities with teratomorphic, or at least non-anthropomorphic, features occupying central positions in the pantheon. These objects, predating the intensive Hellenization process that began in the 7th century BCE, attest to a stage before the pantheon underwent a decisive anthropomorphic transformation.

The conception of reality as inhabited by beings of indeterminate nature – embodying ambiguous powers and sexual characteristics – was widespread among Italic peoples, including the Latins. The Etruscans’ more archaic cosmological framework is reflected in their practice – closely aligned with that of the Umbrians – of appending the name of one deity to another as an epithet, thereby specifying localization, functions, and attributes more precisely. A case in point is the theonym Tinia Calusna, which, by incorporating the name of the underworld god Calu, identifies a chthonic aspect of Tinia, the Etruscan counterpart of Zeus.

This structural similarity across Italic religions has often been ascribed to the historical, and initially cultural, hegemony of the Etruscans over other Italian peoples. However, substantial evidence – including the notable presence of Latin theonyms in the Etruscan pantheon without reciprocal borrowing – suggests the reverse: a significant influence of the Latin world upon Etruscan religion, dating to a very early period, certainly prior to the 8th century BCE. This precedes the emergence, as documented in material culture, of the Etruscans’ economic and political dominance over Italy, which persisted until the Roman conquest began in the 4th century BCE.

This convergence in religious customs and beliefs is also evident in the practice of divination through auspices (auspicia), shared by Latin, Umbrian, and Etruscan populations. Among all Italic peoples, including the Etruscans, the taking of auspices was of paramount importance and constituted a foundational element of authority. As a divinatory technique likely dating back to the Bronze Age, auspicy was employed to ascertain divine favor and was a prerequisite for conferring imperium – civil and military command – first upon kings and later upon republican magistrates.

The auspicium was the initial component of a complex ceremonial system known as augurium (linked etymologically to augere, ‘to augment’), through which mantic practice effected the symbolic empowerment of an individual by conferring specific magical attributes. Augury – whose name derives from avis (‘bird’) and specere (‘to observe’) – entailed the interpretation of avian behavior (flight patterns and vocalizations, i.e., alites and oscines), as well as other signs from the natural and celestial realms (e.g., auspicia ex caelo). The foundational principle of augural doctrine was that divine will could be discerned in such phenomena.

According to the augural concept of deorum sedes, each deity was believed to occupy a specific locus in the celestial vault or underworld, with these regions corresponding to sectors of the sky delineated by the diurnal path of the sun. Favorable, daylight sectors extended from northeast to southwest, whereas unfavorable, nocturnal sectors extended from southwest to northeast.

Auspicy contributed significantly to the development of scientific observation among the Etruscans and Italic peoples more broadly, encouraging systematic classifications in botany, ethology, and especially astronomy. This body of knowledge laid the groundwork for more elaborate theoretical systems, particularly those developed within haruspicina, a later evolution of augural practice. Since augural religion was predicated on the division of space for the purpose of interpreting signs, its refinement necessitated parallel advancements in astronomy and in the measurement of terrestrial space. This, in turn, profoundly shaped religiously grounded urban and topographical speculation. Tradition attributes the foundation of cities and the spatial orientation of architectural elements – walls, gates, and entire urban layouts – to the ritus Etruscus, or Etruscan religious doctrine. Moreover, augural traditions exerted a lasting influence on agronomy; even in the late Roman treatises of the Gromatici, preserved in a complexly layered corpus, continual references are made to augural foundations of land division practices.

It is in this context that fragments of translated Etruscan texts – such as the well-known “Prophecy of Vegoia” (Lasa Vecu in Etruscan) – appear, modeled after Latin translations of passages from the disciplina Etrusca used by haruspices summoned to Rome for the ritual management of prodigies (procuratio prodigiorum), and incorporated into the writings of the Gromatici.

With the rise of the Etruscan economy between the 10th and 8th centuries BCE, the first significant contacts between the Tyrrhenian regions and the East began to take shape. These arose through intense Phoenician interactions, soon followed – beginning in the early 8th century – by Greek ones. The relationship with the Phoenicians led to important cultural acquisitions related to the expression of power, particularly concerning the personal relationship between king and deity, and the display of opulence associated with kingship. The introduction of aruspicina, or divination through hepatoscopy, is undoubtedly linked to this orientalization of a key component of the ideology of power. The Mesopotamian origins of aruspicina are indisputable, and it must have reached Etruria via Phoenician mediation.

The strength of the prehistoric augural tradition, with its established rules, enabled the integration of this Eastern model with the doctrine of auspices, particularly the concept of the deorum sedes. This notion would be further developed within Etruscan aruspicina, with increasing precision in the observation of natural phenomena. The number of divine seats and the possible combinations of multiple deities within the same sedes were expanded and made to correspond to a complex system of peripheral and internal bands – symbolic ‘compartments’ – mapped onto the surface of the liver.

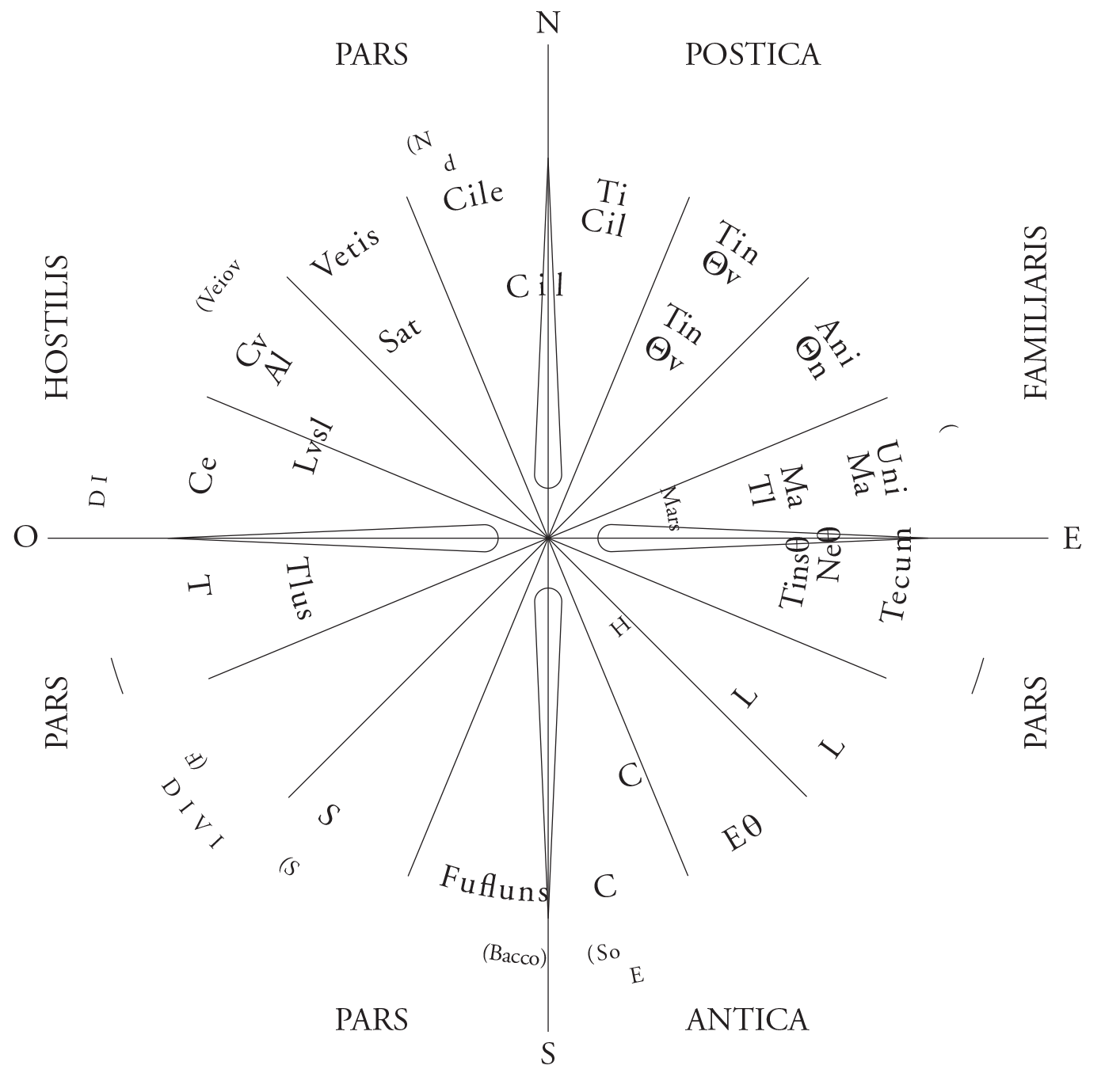

The renowned Liver of Piacenza (fig. 7), a bronze model of a sheep’s liver inscribed with the names of deities corresponding to different parts of the organ, provides an extraordinary guide – if not to full comprehension, at least to the identification of the fundamental structures of hepatoscopic doctrine. Dated, on the basis of its script, to between the 3rd and 2nd centuries BCE in a northern Etruscan context, its concave surface is densely populated with sedes arranged according to the ritual division of space. This space, mirrored by the liver, is divided into sixteen regions – twice the traditional eight of augural doctrine – organized around a peripheral band.

The eight regiones prosperae, or favorable zones associated with superior deities, are located on the right lobe, beginning at the processus pyramidalis – identifiable with the caput iocineris of ancient sources and schematically represented as a pyramid – and ending at the incisura umbilicalis, the fissum, a meridional astronomical reference point. The left lobe contains the eight regiones minus prosperae, the unfavorable ones. The inner part of the right lobe is further subdivided into eight horizontal sedes, of which six belong to the favorable pars familiaris, while two correspond – opposed to two in the left lobe – to another interpretative dimension, the celestial realm (pul), set in contrast with the terrestrial (metlumth).

In the inner portion of the left lobe – the minus prospera zone – a radial sequence of sedes appears, featuring chthonic deities in a graduated order indicating increasingly unfavorable omens, echoing the pattern found in the outer ribbon. The vesica fellea contains four compartments: two favorable and two unfavorable. On the convex side of the model, two inscriptions stand out, one assigning the right lobe to the Sun (Usils), and the other the left to the Moon (Tivs).

This intricate representation and the rules for interpreting signs – based on observations of the venae, fibra, and other features – find extensive support in the literary tradition, though space permits only a few examples here. Omens were read by relating irregularities in specific parts of the organ to the corresponding divine sedes – with the exception of ambiguous areas such as the double caput iecinoris and the adjacent processus papillaris, which, lacking an associated deity, were considered uncertain.

One exemplary case is the favorable presence of Nethuns on the vesica fellea of the Liver of Piacenza, corresponding to Neptune and confirmed by omens associated with water, as attested by Pliny (Naturalis historia, XI, 195). Equally significant is the hostile presence of Maris (Mars) on the same anatomical feature, linked to omens of fire and reflecting a symbolic opposition between water and fire (Cicero, De divinatione, II, 32; Pliny, Naturalis historia, II, 139).

Of no less interest is the alignment between the manubiae – the three zones from which Jupiter could hurl thunderbolts, as reported by ancient sources – and the three sedes of Tin on the Liver of Piacenza, located in the northeastern quadrant, associated with the rising sun.

In summary, the Liver of Piacenza and the ancient sources allow for a reasonably clear reconstruction of the division into partes familiaris and hostilis, the southern orientation of the model, and the cosmological links between divine tetrads, the solar path, and the organization of the universe. Nonetheless, the complex interplay between Greek and Eastern hepatoscopy, astrology, and the disciplina remains an area in need of further scholarly exploration.

The anthropomorphization of Etruscan and Italic deities, coinciding with a deep Hellenization of indigenous lifeways and cultic forms, originates with the earliest contacts between Etruria and the Greek world. Nonetheless, the adoption by the Etruscan ruling elite of a cohesive set of Greek models in religious ideology did not fundamentally alter the underlying attitude toward the divine, nor the system of relationships posited between humans, Nature, and the gods. That said, one may argue that Greek influence, particularly during the early period (8th–6th centuries BCE), significantly contributed to the establishment of a rudimentary system of correspondences between divine powers, their domains of intervention, and their individual identities. It is indeed possible to discern – if not the Latin taxonomy of genius, numen, and deus with their respective uranian and chthonic valences – at least the foundational outlines of a division among gods associated predominantly with celestial or with subterranean realms, which constitute a structural element of the historical Etruscan pantheon.

The strict division between superior and infernal deities in Etruscan religion appears more a modern construct than an ancient reality. The construction of a figure such as Tinia Calusna, or the attribution of a single seat on the Liver of Piacenza to both Tin and Cilen – that is, the supreme sky god and a chthonic goddess of destiny – reflects a conception in which divine domains overlap. This is further confirmed by the idea of a magical correspondence linking Heaven, Earth, and the underworld, accessible through wells and foramina. The fluid identity of many deities and genî (comparable to the Roman Manes), together with the attested existence of ‘chthonic’ thunderbolts – as recorded in the Etruscan libri fulgurales (Pliny, Naturalis Historia, II, 138) – all point to a persistent ambiguity surrounding the loci and spheres of divine influence. This ambiguity, present since prehistoric times, extends well into the historical period.

Thus, rather than being misled by the Olympian gloss of Etruscan iconography, we must regard the permeability of sacred spaces and the mutability of Etruscan deities as original features of their religious system, surviving well into recorded history. This conception is rooted in a cosmology that finds the basis of divine mutability in the bios cycle – human, animal, and plant alike – a worldview largely alien to Greek thought, although Greek Dionysian doctrines would eventually be grafted onto it.

The new urban character of Etruscan civilization, consolidated during the 7th century BCE, along with the sociopolitical structures it engendered, rapidly transformed the relationship between Greek cultural influence and indigenous tradition. The latter, increasingly, became a corpus of rites and ceremonies central to the exercise of power – tenaciously preserved, though increasingly relegated to formal observance. Between the 6th and 5th centuries BCE, esoteric Greek doctrines with soteriological orientations – offering profound perspectives on the cosmos and the afterlife – began to penetrate the aristocratic strata of the more culturally advanced Etruscan cities. Their acceptance was mediated by a continuous engagement with earlier mentalities, as attested in both material culture and visual art, on which much of our current understanding of Etruscan civilization depends.

It is therefore unsurprising that, in the funerary iconography of the late 6th century BCE, the gradual yet persistent diffusion of Dionysianism – conceived as a system of beliefs regarding death, the afterlife, and posthumous salvation – emerges only with difficulty. The Dionysian religion, with its soteriological content and the symbolic instruments necessary for post-mortem survival, undoubtedly functioned as a forerunner to other salvific doctrines introduced into Etruscan culture from the Greek colonial world.

The next significant wave of influence – beginning in the 5th century BCE and extending with notable resonance into later centuries – was connected to the Orphic-Pythagorean doctrines. The Eleusinian initiatory model naturally complemented Dionysian perspectives in formulating a redemptive message for initiates. Together, they overturned both traditional Greek and indigenous cosmologies and gave rise to a new, more intricate religious framework. Iconographic sources attest to the reception of certain Orphic motifs in Etruria, such as the vaticination of Orpheus’s head emerging from the earth – an image evidently integrated into the Etrusca disciplina. Nonetheless, the extent to which the complex cosmological structures of Orphism – as known to us through surviving Greek literature – were assimilated by Etruscan religious thought remains uncertain.

The same applies to the later body of doctrines collectively referred to as ‘Neo-Pythagoreanism,’ which appears to have circulated within the most exclusive circles of the Etruscan aristocracy from the 4th century BCE onward, as evidenced by funerary iconography. Belief in the existence of animulae – souls residing in the underworld and destined for reincarnation – is attested by the depiction of Hades in the frescoes of the Tomb of Orcus II in Tarquinia, which belonged to the aristocratic family of the Spurinnae, one of the most prominent in 4th-century Tarquinia. In the mural, animulae are seen swirling around the figure of the soothsayer Tiresias, in a scene reminiscent of the Virgilian nekyia. Tiresias is portrayed as the prophet of heroic destinies familiar to the gens, and as a symbolic embodiment of haruspical functions, which were well-established within the family – most notably represented by Caesar’s haruspex Spurinna, author of the ominous prediction concerning the Ides of March.

From the 3rd century BCE onward, both literary and visual sources allow us to trace a marked intensification of mystery-religious and philosophical tendencies within Etruscan religious and political ideology. It is from this period – especially between the end of the Republic and the early Imperial age – that the majority of extant fragments of the Etrusca disciplina are preserved, along with the names of several principal authors linked by tradition to haruspical speculation. These figures include both writers of doctrinal manuals and authors of broader scientific, philosophical, and religious treatises in which the disciplina features prominently, due in part to the connection between haruspicy and the natural sciences in texts on prodigies (libri ostentarii), plant lore (arborarii), and meteorology (libri fulgurales, brontoscopic calendars).

Among the earliest known authors of proper haruspical texts are Aulus Cecina, an aristocrat from Volterra active at the end of the Republic and beginning of the Empire, and Tarquitius Priscus, who flourished in the early Imperial period. Later figures include authors of more varied intellectual scope, such as Nigidius Figulus – likely of Etruscan descent – who was also politically active in the first half of the 1st century BCE, and Attalus, known primarily through Seneca’s laudatory reference.

All of these authors reveal strong influences from Greek philosophical thought, particularly those concerned with haruspical doctrine. The most compelling among them is undoubtedly Nigidius Figulus, whom ancient sources associated with the Neo-Pythagorean circles (Cicero, Timaeus, 1; Jerome, Chronicon, Volympiades 183.4). His intellectual breadth is evidenced by works of naturalistic scope (De hominum natura, De animalibus, De ventis, Sphaera) and of a divinatory character (De extis, De somniis, De augurio privato), in which astrology plays a prominent role.

The Etrusca disciplina exerted considerable fascination even beyond the traditional circles educated in haruspicy, which, by long-standing custom, included the leading aristocratic families of the Etruscan cities – virtually all the known authors of divinatory treatises belonged to this milieu. Such is the case with the elusive Attalus, who lived during the reign of Tiberius and fell out of favor with the powerful Praetorian prefect Sejanus (himself of Etruscan origin). Attalus was held in high esteem among contemporary intellectuals and was particularly admired by Seneca, who describes him as the most incisive and eloquent Stoic philosopher of his day – capable of integrating Greek philosophy with the Etrusca disciplina (Naturales quaestiones, II, 50, 1).

Due in part to the widespread fascination with occult sciences in this period, the century spanning the end of the Republic and the early Julio-Claudian era marks the high point of integration between Roman ruling elites – steeped in both Greek and Roman culture and science – and the remnants of Etruscan aristocracy that had managed to preserve a coherent memory of their national divinatory knowledge. Unsurprisingly, it is to this period that the majority of surviving fragments of the libri haruspicini, fulgurales, rituales, fatales and Acheruntici – the traditional subdivisions of the disciplina – can be dated. It is likely that the most widely disseminated versions of these texts were those edited by Tarquitius Priscus.

After the Julio-Claudian era, the notion of an Etruscan-origin aristocracy effectively disappears, and with it any genuinely indigenous development of the Etrusca disciplina. As Emperor Claudius lamented – in his celebrated speech to the Senate advocating for the preservation of the national Etruscan college of sixty haruspices (Tacitus, Annales, XI, 15) – from the mid-1st century CE onward, historical records refer only to haruspices of increasingly diverse origins. It was these increasingly provincial haruspices who ensured the prolonged survival of Etruscan haruspical traditions, albeit through the mechanical repetition of the speculative and practical models developed during the golden age between the mid-4th century BCE and the end of the Republic. Remarkably, the legacy persisted until the very end of the Roman Empire: in 409 CE, Etruscan haruspices – or those claiming to be such – came to Rome, then under siege by Alaric, to offer their services in an attempt to avert disaster (Zosimus, Historia Nea, V, 41 s).

Mario Torelli

References

- Adorno 1991-92: Adorno, Francesco, La filosofia antica, Milano, Feltrinelli, 1991-1992, 4 v.

- Aveni 1994: Aveni, A. - Romano, G., Orientazioni di templi e rituali etruschi, “Rivista di Archeologia”, 18, 1994, p. 57 ff.

- Bloch 1963: Bloch, Raymond, Les prodiges dans l’antiquité classique, Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, 1963, p. 34 ff.

- – 1966: Bloch, Raymond, Liberté et déterminisme dans la divination étrusque et romaine, in: La divination en Mésopotamie ancienne et dans les régions voisines, Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, 1966, p. 159 ff.

- – 1986: Bloch, Raymond, Réflexions sur le destin et la divination haruspicinale en Grèce et en Étrurie, in: Iconographie classique et identités régionales, publié sous la direction de Lilly Kahil, Christian Augé et Pascale Linant de Bellefonds, Athènes, École française d’Athènes; Paris, Diffusion de Boccard, 1986, p. 77 ff.

- – 1989: Bloch, Raymond, Points de vue actuels sur la religion étrusque, in: Atti del Secondo congresso internazionale etrusco, Firenze, 26 maggio-2 giugno 1985, Roma, G. Bretschneider, 1989, 3 v.; v. II, p. 895 ff.

- Bottini 1992: Bottini, Angelo, Archeologia della salvezza. L’escatologia greca nelle testimonianze archeologiche, Milano, Longanesi, 1992.

- Briquel 1990: Briquel, Dominique, Divination étrusque et mantique grecque. La recherche d’une origine hellénique de l‘Etrusca disciplina’, “Latomus”, 49, 1990, p. 321 ff.

- – 1997: Briquel, Dominique, Chrétiens et haruspices. La religion étrusque, dernier rempart du paganisme romain, Paris, Presses de l’École Normale Supérieure, 1997.

- Brown 1986: Brown, J.P., The Templum and Saeculum. Sacred space and time in Israel and Etruria, “Zeitschrift für Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft”, 98, 1986, p. 415 ff.

- Capdeville 1990: Capdeville, Gérard, Kritische Beobachtungen zur traditionellen Vorstellung der etruskischen Disziplin, in: Die Welt der Etrusker, hrsg. von Huberta Heres und Max Kunze, Berlin, Akademie-Verlag, 1990, p. 341 ff.

- Clemen 1936: Clemen, Carl, Die Religion der Etrusker, Bonn, Röhrscheid, 1936.

- Colonna 1993: Colonna, Giovanni, A proposito degli dèi del Fegato di Piacenza, “Studi Etruschi”, 59, 1993, p. 123 ff.

- Cristofani 1993: Cristofani, Mauro, Sul processo di antropomorfizzazione nel pantheon etrusco, in: Miscellanea etrusco-italica, Roma, Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, 1993-; v. I, 1993, p. 9 ff.

- Dumézil 1972: Dumézil, Georges, Remarques sur les trois premières regiones caeli de Martianus Capella, in: Mélanges offerts à Max Niedermann à l’occasion de son soixante-dixième anniversaire, Genève, Slatkine Reprints, 1972, p. 102 ff.

- Enking 1947: Enking, Ragna, Etruskische Geistigkeit, Berlin, Gebr. Mann, 1947.

- Giglioli 1944: Giglioli, Giulio Quirino, La religione degli Etruschi, in: Storia delle religioni, diretta da Pietro Tacchi Venturi, rist. accresciuta della 2. ed., Torino, Utet, 1944, 2 v.; v. I, p. 771 ff.

- Gourevitch 1965: Gourevitch, Danielle, Anatomie et religion chez les Étrusques, “La Presse Médicale”, 51, 1965, p. 2961 ff.

- Hall 1986: Hall, J.F., The Saeculum Novum of Augustus and its Etruscan antecedents, in: Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt, hrsg. von Wolfgang Haase, Berlin, W. de Gruyter, 1972-; v. II, 16, 3, 1986, p. 2564 ff.

- Herbig 1922: Herbig, Gustav, Religion und Kultus der Etrusker, “Mitteilungen der Schlesischen Gesellschaft für Volkskunde”, 33, 1922, p. 1 ff.

- – 1957: Herbig, Reinhard, Zur Religion und Religiosität der Etrusker, “Historia”, 6, 1957, p. 123 ff.

- – 1965: Herbig, Reinhard, Götter und Dämonen der Etrusker, hrsg. und bearb. von Erika Simon, Willsbach, Scherer, 1948 (2. ed.: Mainz, Zaberndruck, 1965).

- aeger 1961: Jaeger, Werner W., La teologia dei primi pensatori greci, Firenze, La Nuova Italia, 1961 (orig. title The theology of the early Greek philosophers, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1947).

- Jannot 1998: Jannot, Jean-René, Devins, Dieux et Démons. Regards sur la religion de l’Étrurie antique, Paris, Picard, 1998.

- Koch 1934: Koch, Carl, Bericht über die neuesten Forschungen und Fragestellungen aus dem Gebiet der etruskischen Religion in Deutschland, “Studi Etruschi”, 8, 1934, p. 425 ff.

- – 1939: Koch, Carl, Gestirnverehrung im alten Italien, Frankfurt am Main, V. Klostermann, 1939.

- Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae, Zürich, Artemis Verlag, 1981-1997, 8 v.

- Linderski 1986: Linderski, Jerzy, The augural law, in: Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt, hrsg. von Wolfgang Haase, Berlin, W. de Gruyter, 1972-; v. II, 16, 2, 1986, p. 2146 ff.

- Maggiani 1982: Maggiani, Adriano, Qualche osservazione sul fegato di Piacenza, “Studi Etruschi”, 50, 1982, p. 53 ff.

- – 1984: Maggiani, Adriano - E. Simon, Il pensiero scientifico e religioso, in: Gli Etruschi. Una nuova immagine, a cura di Mauro Cristofani [et al.], Firenze, Giunti Martello, 1984, p. 136 ff.

- Mansuelli 1998: Mansuelli, Guido A., Disciplina etrusca e pensiero scientifico, “Annali della Fondazione per il Museo C. Faina”, 5, 1998, p. 105 ff.

- Massa Pairault 1998a: Massa Pairault, Françoise-Hélène, Libri Acherontici - Sacra Acheruntia. Culture grecque et Etrusca disciplina, “Annali della Fondazione per il Museo C. Faina”, 5, 1998, p. 83 ff.

- – 1998b: Massa Pairault, Françoise-Hélène, Religion étrusque et culture grecque, “Annali della Fondazione per il Museo C. Faina”, 5, 1998, p. 325 ff.

- Meer 1979: Meer, Lammert Bouke van der, Iecur Placentinum and the orientation of the Etruscan haruspex, “Bulletin van der vereeniging tot bevordering der kennis van antieke beschaving”, 54, 1979, p. 79 ff.

- – 1987: Meer, Lammert Bouke van der, The Bronze Liver of Piacenza. Analysis of a polytheistic structure, Amsterdam, Gieben, 1987.

- – 1989: Meer, Lammert Bouke van der, The evolution and structure of the Etruscan Pantheon, “Cosmos”, 5, 1989, p. 77 ff.