In ancient Greece, the sciences did not emerge fully formed, like Athena springing fully armed from the head of Zeus. Even the terminology used to refer to various disciplines acquired clarity and stability only gradually, and at different paces across fields. The Homeric poems contain a rich trove of observations and beliefs about the stars, atmospheric phenomena, the properties of sound and light, as well as geographical and ethnographic insights – so much so that they have often been described as a kind of ‘tribal encyclopedia.’ Since antiquity, Plato referred to Homer as the teacher of all Greeks, and the author of On Joints (part of the Hippocratic corpus) cited Homer as an authority on matters concerning livestock.

In the Homeric world, it was believed that the knowledge of the poet-singer extended beyond what was immediately perceptible, encompassing the past, present, and future. For this reason, it was closely aligned with that of the mántis, the soothsayer (Iliad I, 70). In both cases, knowledge was accessed through divine intervention. The poet’s authority stemmed from inspiration by Apollo and the Muses, who had seen all things and “knew everything” (Iliad II, 484–487; Odyssey VIII, 487–491). Such divine sources conferred not only artistic skill, making the poet a kind of verbal craftsman, but also a privileged access to content inaccessible to most. Yet it would be a mistake to think that only poets and seers possessed such inspired knowledge: even a skilled carpenter (téktün) owed his expertise to the goddess Athena (Iliad XV, 410–412).

Much later, in the second century CE, Plutarch recorded efforts to assign each of the nine Muses to specific fields of knowledge, according to a tripartite scheme of philosophy, rhetoric, and mathematics – the latter divided further into music, arithmetic, and geometry (Quaestiones conviviales, IX, 14, 744a–f). Such classifications presupposed a disciplinary separation that is entirely absent from the Homeric texts. The information in those poems is woven into narratives designed to transmit ethical codes rather than to constitute a structured body of knowledge. If one speaks of a Homeric ‘encyclopedia,’ it is more accurate to say it conveyed what one needed to know, rather than all that could or should be known.

The same applies to Hesiod, who attributed his own knowledge of past, present, and future to the inspiration of the Muses (Theogony, 1–43). A large portion of his Works and Days offers advice on when to farm or sail, based on observations of the stars or weather, without claiming to be a comprehensive treatise on agriculture or navigation. In an oral culture, such knowledge was transmitted through household apprenticeship. Hesiod himself admitted to lacking expertise in navigation, yet claimed to understand the ‘measures’ of the sea and the will of Zeus – thanks, again, to the Muses (Works and Days, 648–650; 661–662). Thus, the poet portrayed himself as a mediator between the world of gods and men, capable of anchoring even practical knowledge within a divine framework.

In the earliest texts, the word sophós (‘wise’) referred primarily to general competence: the skill of artisans, soothsayers, poets, and physicians, or more broadly, the ability to handle individual and public affairs. In the Homeric poems, Odysseus is described using epithets built on the prefix poly- (‘much’): he is someone who has seen much, knows much, and devises much in adversity. The same prefix appears in polymathía, literally ‘learning many things,’ whether by direct experience or instruction. This trait would later be celebrated in Homer by an apocryphal work attributed to Plutarch (On the Life and Poetry of Homer). However, when the term first appears in a fragment by Heraclitus of Ephesus (early 5th century BCE), it carries a negative connotation: “Polymathy does not teach understanding; otherwise, it would have taught Hesiod, Pythagoras, Xenophanes, and Hecataeus” (DK 22 B 40). Heraclitus does not specify the content of such knowledge, and the mention of Pythagoras should not lead us to assume it was mathematical in nature – mathematics being referred to later as the mathémata par excellence, the ‘things taught.’ In fact, early sources from Herodotus to Isocrates and Plato do not associate Pythagoras with mathematics.

Another Heraclitean fragment explains his critique of Hesiod: “Hesiod is master of many things; yet he failed to understand day and night, which are one” (DK 22 B 57). Here, Heraclitus faults not the extent of Hesiod’s learning, but his failure to recognize underlying unity in seemingly separate phenomena – and the presumptuous claim to mastery that followed. Heraclitus seems unaware that Xenophanes had also criticized Homer and Hesiod, reproaching them for shaping public belief (DK 21 B 10). Xenophanes denied divine revelation and argued instead for a slow human search for truth over time (DK 21 B 15).

In Heraclitus’ view, Pythagoras’ polymathíā amounted to apparent rather than true wisdom (sophía), assembled from the writings of others (DK 22 B 129). It is unclear which texts Pythagoras used, but what emerges here is a novel reality: not merely writing, but books – sources to be excerpted or plagiarized for personal claim. Such an idea is absent from Homer and Hesiod, whose poems contain no reference to books as repositories of knowledge.

Later depictions of the early ‘philosophers’ or physiologoi attribute to them inquiries and doctrines across a broad spectrum – from celestial and meteorological to embryological phenomena and even geometry, as in the cases of Thales, Anaxagoras, Democritus, and Pythagoras. These images, shaped from Aristotle and Theophrastus onward, rest on the assumption of differentiated scientific disciplines. The catalog of Democritus’ works, compiled by Thrasyllus in the 1st century CE, already reflects the figure of a learned man mastering diverse fields. Yet this list cannot be taken as proof of a well-defined disciplinary system. If we examine a mid-5th-century prose work like Herodotus’ Histories, we find a seamless intermingling of historical, geographical, zoological, botanical, and anatomical information – offered without concern for disciplinary boundaries.

The figure of the polymathés reemerges toward the end of the same century in Plato’s portrayal of Hippias of Elis (Hippias major 285b7–e2; Hippias Minor 366c5–368e1; Protagoras 318d9–e4). In these dialogues, Plato does not use the term polymathía, but describes Hippias as “absolutely the most knowledgeable of all men in many téchnai” (Hippias minor 369b), and presents a wide-ranging list of areas in which Hippias claimed expertise. Although the list is not exhaustive, several domains recur across the three dialogues: (1) the stars and celestial phenomena; (2) geometry; (3) number (arithmós) and calculation (logismós); and (4) grammatical and musical studies. Both dialogues also mention his interest in mnemonics. In the Hippias major, archaiología – the recounting of genealogies and city foundations – is included, while the Hippias minor goes so far as to include the making of handicrafts, garments, and jewelry.

Where did Hippias acquire all this knowledge? Plato does not specify, but it is conceivable that much of it came from written sources. In the opening of one of his own writings (DK 86 B 6), Hippias himself explains that his work was the result of compiling material selected from various other texts – both poetic and prose, Greek and non-Greek – based on thematic relevance and importance. Nevertheless, he regarded the outcome as original, believing that originality lay not in the sources, but in the way they were interwoven. In his view, drawing from others’ writings was not a fault, unlike what Heraclitus had reproached Pythagoras for. Recent scholarship suggests that this text by Hippias may represent the earliest form of what would later become philosophical doxography. It may also have included material pertaining to scientific disciplines such as geometry.

Plato’s depiction of Hippias thus presents him as an encyclopedic figure, capable of mastering and exhibiting a remarkable array of knowledge, extending even into practical and manual skills. His uniqueness lay in this all-encompassing learning, which freed him from dependence on specialists. It was a kind of comprehensive knowledge that, for the most part, exceeded the capacity of any single individual. Yet the terminology Plato uses to describe and differentiate these fields remains fluid and not strictly defined.

If we compare the domains of knowledge attributed to Hippias with those listed in Prometheus Bound (lines 450–506), a text attributed to Aeschylus and likely written between the time of Heraclitus and that of Hippias, we gain insight into the evolving classification of intellectual disciplines. The catalogue of téchnai that Prometheus gives to humanity consists exclusively of practical arts: animal husbandry, navigation, the ability to track star risings and seasonal changes, divination, healing, and the inventions of writing and numerical notation. The reference to numbers here does not allude to Pythagorean or theoretical arithmetic; rather, it concerns basic tools for counting and calculation essential for survival.

This catalogue reflects the literary motif of the prõtos heuretés – the archetypal first inventor – emphasizing the utility of knowledge. Interestingly, geometry is not included, although Herodotus, writing not long after Aeschylus, attributes the invention of what he already refers to as ‘geometry’ to the Egyptians (Histories II, 109.3). Still, in Book I of his Histories (sections 74.1–2; 75.3–6; 170.1–3), Herodotus does not use the terms ‘astronomy’ or ‘geometry’ as clearly defined disciplinary labels when discussing Thales’ scientific and technical achievements. The same is true for his reference to Solon’s calendar reforms (I, 32.2–4).

The situation appears different – and more clearly delineated – in another play: Aristophanes’ Clouds, first performed around 423 BCE and revived a few years later. This comedy portrays the investigation and teaching of a broad range of knowledge under the direction of a single figure: Socrates (verses 143–217). The terms geometry and astronomy are employed not as the names of established sciences, but as references to tools – such as rulers and compasses – used to measure the paths of the stars or the dimensions of plots of land. From this perspective, geometry seems closely allied with geography, in line with the literal meaning of the term: “measurement of the earth.” The word geography itself, however, would only begin to designate a scientific discipline in the third century BCE with Eratosthenes of Cyrene; it remains absent in the works of both Plato and Aristotle.

In addition to geometry and geography, Aristophanes references teachings and inquiries we might describe as anatomo-physiological. It is likely that no clear or universally accepted designation yet existed for those engaged in such studies: Strepsiades, one of the characters, admits he does not know the appropriate name and jokingly suggests merimnophrontistaí, loosely translated as “those who trouble themselves with thoughts” (verses 100–101) – a term likely coined by Aristophanes himself. One domain, however, emerges as especially prominent: that which concerns “things up in the air” (metéüra prágmata) (verses 225–234; 489–490; 1283–1284). This emphasis is natural in a play centered on the clouds, which are venerated as new divinities by the intellectuals it caricatures.

To designate those devoted to such study, Aristophanes uses the terms meteürophénakes and meteürosophistaí, literally meaning “frauds who pretend to be experts on metéüra.” The archetype of the meteürosophistaí is Prodicus, who in modern historiography is classified not among the philosophers of nature but among the sophists – a distinction that this context throws into question. Likewise, the sophist Protagoras was targeted by the comic poet Eupolis (DK 80 A 11), who mocked him as an impious deceiver with regard to the metéüra.

Besides Socrates and Prodicus, Aristophanes also references Meton, known for reforming the Athenian calendar in 433 BCE and portrayed as a kind of fifth-century Thales – a paradigmatic wise man. In the Birds (verses 995–1009), Meton appears as a character engaged simultaneously in astronomical research, pursued with measuring instruments; in geometric inquiry, such as the problem of squaring the circle; and in urban planning based on geometric models, in the style of the near-contemporary Hippodamus of Miletus. The same Hippodamus is described by Aristotle (Politics II.8, 1267b 22–30) not only as a city planner and architect of political reform, but also as someone who aspired to universal knowledge of phìsis (Nature). It may be for this reason that the later lexicographer Hesychius defines Hippodamus as a meteürológos (DK 39 A 3).

In Aristophanes’ portrayal of Meton, we need not see a strictly accurate biographical sketch, but rather a figure embodying the unification of multiple types of knowledge. Aristophanes does not attempt to distinguish clearly between these domains, nor does he seem to perceive a need to do so. What unites his depictions of intellectuals is their perceived uselessness – symbolized by the recurring label of ‘idleness’ (argía). The values traditionally associated with the prõtos heuretés (first inventor) are here radically inverted.

Aristophanes’ comedies thus mirror a phenomenon distinctive of the later fifth century: the emerging awareness of a type of intellectual life dedicated exclusively to pursuits without immediate utility – what would come to be known as theoretical or contemplative life. One of the earliest significant literary traces of this concept appears in fragments from Euripides’ tragedy Antiope. These fragments seem to allude to Anaxagoras as an emblematic figure: someone who leaves his native city to settle in Athens for the sole purpose of pursuing study. At the heart of this new way of life is meteürología – the investigation of celestial, atmospheric, and climatic phenomena.

In a text likely written in the last decades of the fifth century, Gorgias refers to the meteürológoi, presenting them as a group distinct from orators and philosophers engaged in political or judicial discourse (Encomium of Helen, §13). By this period, inquiry into the metéüra may already have been connected with interest in subterranean phenomena (cf. Plato, Apology 18b–c, 19b–c). Both types of phenomena share a key characteristic: they are hidden from direct observation and must be interpreted through analogy or overarching theories of the cosmos. The author of On Ancient Medicine refers to such explanatory models as “hypotheses” (1.3).

Against this backdrop, general conceptions of the investigation of Nature (perì phìseüs historía) began to take shape – conceptions that encompass not only meteürología but also theories concerning human nature: anatomy, physiology, and embryology. The study of Nature could include inquiries into the shape of the Earth, the origins and development of living beings, or the organ responsible for human thought (On Ancient Medicine 20.1–2; Plato, Phaedo 96a; Xenophon, Memorabilia I.1.11).

Later, Aristotle would refer to the early thinkers as physiológoi, though doing so through the lens of his own conception of physiké – Nature as an autonomous field of inquiry, or philosophy of nature. This branch of knowledge would later be claimed by the philosophical schools of the Hellenistic era as one of the three major areas of philosophy, alongside logic and ethics.

The emergence of specialized knowledge can be assumed to coincide with public recognition that only a select few possess it. It is no coincidence that one of the earliest explicit articulations of this idea – predating even Plato (Ion 537c 6; Charmides 171a 4–9) – is found in the medical treatise On Ancient Medicine (4.1): “It is not appropriate to call someone a technician (technítäs) in matters where no one is a layperson (idiótäs), or where everyone possesses knowledge (epistémones) by virtue of use and necessity.” According to this view, the differentiation between the human diet, regulated by cooking, and the diet of animals does not pertain to specialized knowledge; however, the identification of a diet for the sick, distinct from that of the healthy, does.

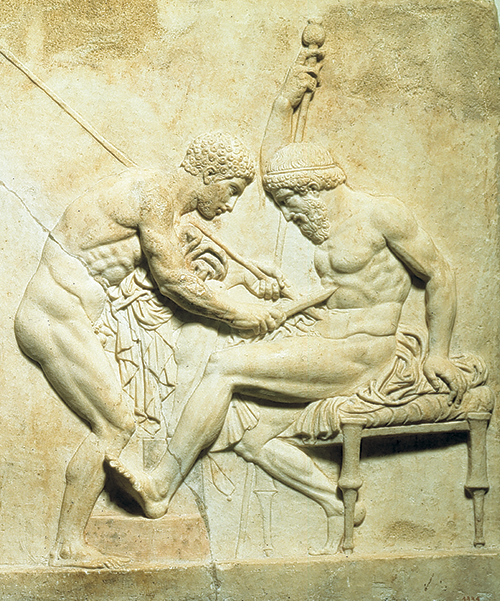

Already in the Homeric poems, medicine is portrayed as a recognized form of specialized knowledge. The physician, alongside the poet, the soothsayer, and the carpenter, is designated as a dämiourgós (Odyssey XVII, 383–387): a professional who offers expertise to the public and travels to serve those in need. The physician is described as “a man worth many others” (Iliad XI, 514), enjoying high social esteem in contrast to beggars, who were shunned.

When, in the sixth century BCE, Solon sought to exemplify in his elegy To the Muses the diversity of human endeavors, he listed navigation, agriculture, manual crafts, poetry, divination, and medicine. From its earliest representations, medicine thus appears as a specialized form of knowledge, requiring instruction for those wishing to become practitioners. In the Iliad, the medical heroes Machaon and Podalirius receive their art from the gods; however, in general, the transmission of medical expertise was expected to occur within the family. It is therefore significant that, according to tradition, both Thessalus and Polybus – respectively son and son-in-law of Hippocrates – became physicians, and that Eryximachus, the physician featured in Plato’s Symposium, was the son of the physician Acumenus.

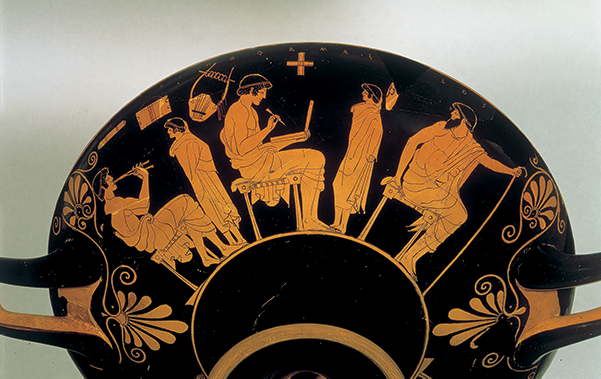

The famous Hippocratic Oath, dating from the 4th century BCE, attests that, at least in certain circles, aspiring physicians were welcomed into the master’s household. According to Plato (Respublica V, 467a), family apprenticeship remained the primary mode of transmitting craft knowledge in his day. Yet in the case of medicine, sculpture, and painting, he also notes the existence of paid instruction – by Hippocrates, Polyclitus, and Phidias respectively (Protagoras 311b–c). This was private education, unregulated by any official curriculum or examination system.

Herodotus reports the existence of highly regarded physicians in cities such as Aegina and Croton (III, 131.1–2). Galen (De methodo medendi I.1, K X 5–6) speaks of an ancient and healthy rivalry among groups of physicians, which he likens to choruses associated with specific regions: two in Asia – on the islands of Cos and Cnidus – and one in Italy, including figures such as Empedocles and Philistion. A fourth-century BCE inscription from Delphi also refers to a koinón, or community, of physicians from Cos and Cnidus. While these references have sometimes been interpreted as indicating the existence of formal schools or research centers – like the later Museum of Alexandria – medical training in these periods still retained a certain degree of informality and was not yet fully institutionalized.

Whether this model of specialization in medicine or the crafts can be extended to other domains of knowledge remains uncertain. There is no clear evidence of socially recognized professionals in mathematics or astronomy, nor of dedicated schools for teaching these disciplines. Yet the fact that several fifth-century mathematicians, such as Enopides and Hippocrates, originated from the island of Chios may suggest the presence of embryonic research communities.

The Pythagorean community in Croton and later Tarentum is perhaps too specific to generalize to the entire Greek world. Nonetheless, Aristophanes’ Clouds depicts, albeit in parody, a space set apart from public life – the phrontistérion, or “thinking-shop” – where studies such as those previously discussed are taught and practiced under Socrates’ guidance. This implies that, at least in Athens, such knowledge was no longer cultivated solely by isolated individuals.

In the Republic (VII, 528b–c), Plato comments on stereometry in a way that reflects a rare classical Greek recognition of the importance of public esteem, organization, and institutional structure in fostering scientific inquiry. He acknowledges that the study of stereometry, though lacking societal prestige, nonetheless progresses due to the attraction it exerts on certain individuals. He contends, however, that these disciplines would flourish more rapidly if not left to chance efforts, but instead entrusted to the leadership of a capable guide under the auspices of a city aware of their significance. This, of course, did not occur in classical Greece, but Plato’s own leadership at the Academy may be seen as a response to such a need.

It is likely with this background in mind that Dicearchus, a student of Aristotle, attributed the progress in mathémata during Plato’s time – particularly in metrology, geometry, optics, and mechanics – to Plato’s coordinating role as an ‘architect.’ Plato is said to have assigned specific problems to competent researchers, including Eudoxus of Cnidus. The image of Plato leading collective investigations evidently circulated widely, as evidenced by the comic sketch reported by Epicrates, where various scholars – including a Sicilian physician – gather around Plato to develop botanical definitions and classifications (Athenaeus, II, 59c–f).

Alongside oral transmission, a written medical literature intended for future physicians began to emerge in the fifth century. According to Galen (Anatomicae administrationes II.1, K II 280–282), the writing of anatomical notes began when medicine started to be transmitted outside the familial context. Examples include the Epidemics, attributed to Hippocrates, which took the form of expandable clinical case collections – open to additions by the author or by subsequent physicians. Similar compilations likely gave rise to the now-lost Cnidian Sentences, criticized by the author of On Regimen in Acute Diseases. The idea of medical knowledge as cumulative, built upon by successive generations, began to take hold. The author of On Regimen echoes this view: rather than refuting his predecessors, he praises them and adds his own contributions (I.1.1–3).

Writing thus became a reservoir of knowledge, enabling transmission independent – at least partially – of oral instruction. It is no coincidence that the late fifth century also saw the earliest attestations of libraries (Euripides, Hippolytus 451–454; Xenophon, Memorabilia I.6.14; IV.2.1 and 8.9). Still, it would be incorrect to assume that this learned, literate form of medicine supplanted all others; alternative therapeutic practices continued to be employed throughout antiquity.

For other disciplines, documentation is not as abundant, and it is difficult to extend to them what we know from the case of medicine. Nonetheless, it must be acknowledged that many forms of technical knowledge continued to be transmitted orally through apprenticeship, without ever reaching the level of written expression. A further obstacle was the persistence of professional secrecy, which did not apply to agriculture – hence Xenophon’s decision to devote a written treatment to this field (Oeconomicus XV–XVI).

Precisely toward the end of the fifth century, a significant divide began to sharpen between techniques related to manual labor and those independent of it. This division is explicitly articulated by Plato, who attributes to Gorgias the distinction between a praxis performed by the hands and one carried out through speech – namely, rhetoric. However, in the same dialogue, Socrates effectively demonstrates that this second kind of praxis also encompasses arithmetic, the technique of calculation, geometry, and many other téchnai (Gorgias 450b3–e2; Politicus 258c3–e5).

In his Commentary on the First Book of Euclid’s Elements, Proclus reports that writings on geometry existed as early as the late fifth century BCE – specifically those by Hippocrates of Chios. Proclus likely derived his information, either directly or indirectly, from the History of Geometry by Eudemus of Rhodes, a student of Aristotle. When Simplicius, a later commentator on Aristotle, recounts Hippocrates’ various attempts to solve the problem of the quadrature of the lunulae, he states that he is following ‘verbatim’ the account given by Eudemus. Nevertheless, Simplicius finds it necessary to supplement that account with references to Euclid’s Elements to clarify points that are insufficiently developed – due to the summarizing (hypomnämatikón) style of Eudemus, which adhered to the conciseness typical of “archaic usage.” The text presented by Simplicius is thus the result of a double mediation relative to the original text of Hippocrates, though it is plausible that Hippocrates’ writings already exhibited features that would later characterize the style of Euclidean geometry.

Despite such instances, oral instruction remained an essential mode of transmission even in geometry. According to Plato, the teachings of both Hippias and Theodorus of Cyrene (active between the fifth and fourth centuries BCE) were oral. We must also recall the extraordinary example, in the Meno, of a slave who arrives at the solution to a geometrical problem through oral guidance alone.

Conversely, we also have the opposite case: a manual technique that ascends to the level of written theory – namely, sculpture. The ancients attributed to the sculptor Polykleitos, sometime in the second half of the fifth century BCE, the authorship of a treatise entitled Canon, in which the proportional relationships among the various parts of the human body were codified. This theoretical work was paired with a statue that visually embodied these proportions. If by “manual” we mean a compendium of general rules, explanations, prescriptions, recommendations, and prohibitions – designed to guide a student toward mastery of a skill – then Polykleitos’ book, supported by the illustrative power of the statue, can indeed be considered a manual. Such a manual did not replace direct workshop apprenticeship, but it offered valuable support during the learning process and served as a mnemonic device for the trade’s principles.

It is uncertain whether this treatise was intended solely for sculptors. One cannot exclude the possibility that it was also directed toward a broader audience interested in understanding the principles governing statuary, and thus in acquiring criteria for judging and appreciating artistic results.

Once technical knowledge is committed to writing, it may extend beyond the confines of the workshop and the bounds of familial or professional groups, opening itself to a faceless audience – distant in both time and place – composed of new recipients not necessarily intent on acquiring the trade. Writing changes both the scope and mode of circulation of knowledge. Addressing readers beyond the circle of practitioners, technical knowledge may come to be studied not just for its reproduction and transmission, but also for its analysis and critical discussion. In this way, knowledge cultivated by specialists can be situated within broader theoretical and cultural frameworks, allowing for comparisons, distinctions, integrations, or contrasts with other forms of knowledge.

The public character that displays of knowledge acquired in the latter half of the fifth century BCE was closely connected to the growing taste for dispute – a taste that extended beyond experts. This appetite found fertile ground in the rise of political and judicial debate, both central features of the pólis as a political structure. The Hippocratic treatise The Nature of Man (1.2–3; 2.1–2) refers to contests in which multiple speakers confronted one another on a given topic – in this case, human nature – with the aim of prevailing before an audience. These competitions were not limited to medicine, but touched on other fields as well. Gorgias (Encomium of Helen, §13) mentions opposing discourses among meteürológoi, while another Hippocratic treatise, De arte (Perì téchnäs), refers to many who “make an art of criticizing the arts,” especially medicine, denying that it is a true téchnä.

The context (1.1–3) suggests that these critics were not necessarily physicians – nor perhaps was the author of the treatise himself. The text recalls another speech in defense of the téchnai (9.1). Some link this writing to a passage from Plato’s Sophist (232d–e), in which the young Theaetetus interprets a statement as an allusion to arguments attributed to Protagoras: “There are publicly available writings containing all the objections that should be made against the téchnai, collectively and individually, for those who wish to learn them.” This may refer to a work on mathémata attributed to Protagoras, in which all forms of knowledge – not just mathematics in the narrow sense – were critically examined.

If this critique included geometry, as suggested by Aristotle, who reports that Protagoras denied that “a circle and a straight line are tangent at a point” (Metaphysics II, 997b 35–998a 4), then we would have clear evidence that geometry was already being treated as a distinct téchnä or máthäma, open to criticism from non-specialists and subject to challenge in its foundational assumptions.

Hippias’ polymathía thus appears inverted in Protagoras’ work into a kind of systematic refutation of the téchnai. It is no coincidence that Plato portrays Protagoras reproaching other sophists – particularly Hippias – for corrupting youth by encouraging them to focus on specific skills, “teaching them calculation, astronomy, geometry, and music” (Protagoras 318d 9–e 4).

The efforts by Antiphon and Brison (active between the fifth and fourth centuries BCE) to solve the problem of squaring the circle – though they were not professional mathematicians – along with the comic portrayal of Meton by Aristophanes as someone interested in such problems, reflect the diffusion of a taste for difficult or insoluble challenges, echoing a tradition of riddles and puzzles. According to Aristotle (De sophisticis elenchis IX.11, 171b 34–172a 7; Physica I.2, 185a 14–17), these attempts were grounded in assumptions external to geometry, which, as a science, was founded on its own principles. Hence, Aristotle argues, it was not the task of geometers to refute such flawed premises.

In the case of medicine, openness to a broader public was obviously tied to the need for patients and their families to choose their physician. Already in the fifth century – and certainly in the fourth – some cities appointed public physicians (Xenophon, Cyropaedia I.6.15). In these contexts, the physician had to demonstrate his competence, and his reputation played a key role. Yet the limited effectiveness of ancient medicine, starkly revealed at the start of the Peloponnesian War – when many physicians themselves succumbed to the Athenian plague (Thucydides II.47.4) – highlighted the importance of the recurring acknowledgment in Hippocratic texts of the incurability of certain diseases.

This situation forced physicians to rely not only on practice, but also on speech – and sometimes writing – to persuade the public, addressing general issues in medicine beyond immediate needs. Plato, in the Laws, contrasts the physician of free men, who explains treatments, with the physician of slaves, who simply applies them (IV, 720a–e; IX, 857c–d).

The emergence of an audience interested in medical issues is also confirmed by Thucydides, who, in his account of the Athenian plague, includes a technically informed description of symptoms and conjectures about the disease’s causes – thus adopting a quasi-medical vocabulary. Similarly, in Plato’s Symposium, Eryximachus delivers a praise of Eros grounded in medical theory during a convivial gathering of learned men. In the Republic (III, 405a–d), medicine is explicitly paired with legal matters as a topic of interest – one that, in Plato’s view, had garnered undue attention even from free citizens who did not practice the profession.

On the other hand, the presentation – oral or written – of conflicting conceptions of medicine could lead non-specialists (dämótai or idiótäs, the common people) to doubt whether medicine constituted genuine knowledge. This situation mirrors the uncertainty generated by disagreement (diaphünía) among soothsayers when interpreting similar signs (De diaeta acutorum, 7–8, 44). This explains the anxiety evident in some physicians’ efforts to demonstrate the scientific status of their art despite its limitations. The author of On Fractures deems it necessary to provide fellow physicians with an apomáthäma, a kind of reverse teaching derived from examples of errors committed by impostor doctors (ch. I, XXV). Such warnings, however, could also serve lay readers in discerning genuine physicians from charlatans.

We may assume that in other fields, such as arithmetic or geometry, the stakes were not as dramatic as in medicine, though meteürología faced a different kind of challenge. Interest in this field among members of the Athenian elite is exemplified by the wealthy Callias, who hosted visiting intellectuals like Protagoras, Prodicus, and Hippias (Plato, Protagoras). A tradition from Plato to Plutarch (Pericles 6.1–5) credits Pericles with an interest in the metéüra; Plutarch even recounts his presence at a public debate between Anaxagoras and the seer Lampon over the appearance of a one-horned goat – interpreted either as a divine sign or a natural anomaly.

In such contexts, showing interest in complex, cutting-edge topics could also bestow prestige. Over time, a link emerged between military training and the acquisition of geometrical and astronomical knowledge. Polybius (IX.14–16; 19–21) later echoed a widespread Hellenistic belief: that generals must possess not only mechanical knowledge (for building war machines), but also astronomical and geometrical skills – for eclipses and battlefield tactics, respectively. This idea was already present in Plato (Republic 527d2–6).

According to Plutarch (Nicias 23.3–5), Anaxagoras authored a book on lunar phases that gained him fame but also made him a target of the general distrust directed toward “physicists and meteüroléschai” – those who, literally, “chattered about celestial matters.” Plutarch claims that only Plato’s writings later legitimized the mathémata for a broader audience, though some invention likely colors this account. The so-called Diopithic decree of 438–437 BCE, reported by Plutarch (Pericles 32.2), allegedly banned the teaching of the metéüra or metársia – and the historicity of trials involving intellectuals like Anaxagoras remains debated.

Still, it is hard to deny the presence of widespread suspicion toward such inquiries. Plato’s Apology (26d) alludes to Anaxagoras’ book as a source of controversy. These suspicions ranged from fears of religious subversion and corruption of youth to concerns about the irrelevance of such studies for the civic, ethical, and military roles of the citizen. The more lenient critics focused on their uselessness – a theme debated in the philosophical schools of the fourth century.

At the Academy and the Lyceum, figures such as Thales were ridiculed for neglecting practical matters: the tale of him falling into a well while stargazing appears in Plato’s Theaetetus (174a) and originates in Aesop (fable no. 65). Similarly, Hippocrates of Chios is mocked for his ineptitude in financial affairs (Ethica Eudemia VIII.14, 1247a 15–21). Yet the same Thales, according to Aristotle (Politics I.11, 1259a 5–21), was able – thanks to his astronomical-meteorological insight – to foresee a good olive harvest, seize control of the presses, and make a profit, thus proving that scientific knowledge could yield practical returns.

The heart of the matter, however, lay in the education of the young – a concern already emphasized in Aristophanes’ Clouds, where the corrupting influence of teaching “idle” disciplines is dramatized as leading to the subversion of traditional values, such as respect for one’s parents. A key element in Plato’s portrait of the Sophists, including Hippias, is their targeting of wealthy youths, to whom they taught for a fee. In the Protagoras (311b–312b 4; 315a 3–5), Plato stages a conversation between Socrates and the young Hippocrates, a potential student of Protagoras, in which fee-based instruction aimed at producing professionals – like physicians or sculptors – is sharply contrasted with education pursued for non-professional purposes.

Socrates cites the example of teachers in Athens followed by boys not in order to become specialists, but to receive a general education (paideía) befitting a free man and idiótäs. According to Xenophon (Memorabilia IV.7.2–9), it was Socrates himself who outlined the degree to which an “educated” person should be knowledgeable (émpeiros) in geometry, astronomy, arithmetic, and medicine. Xenophon attributes to Socrates precisely the instrumental view of learning that Aristophanes had expressly rejected. For Xenophon’s Socrates, one should study only what was necessary for practical purposes: surveying land for buying and selling, distinguishing between days, months, and seasons, making calculations, and understanding health. Anything beyond these immediate needs – for example, delving deeply into geometry or studying astronomy to understand stars, planets, and their distances – was to be resolutely avoided.

It is reasonable to assume that a significant portion of Greek society, including the culturally advanced Athenians, shared this restrictive view on education. In both the Antidosis and Panathenaicus, Isocrates maintains that those who pursue astronomy, geometry, and other such mathémata are “less helpful than they promise, but more than others believe.” For most people, these studies amounted to idle speculation and meteürología, seen as irrelevant to practical life. Isocrates accepts this prevailing judgment, arguing that there is little benefit in attaining technical precision in such disciplines unless one intends to teach them professionally.

However, if learning is considered on a different level – apart from immediate utility – these studies serve as a kind of intellectual training. They offer a mental “gymnastics,” cultivating agility and capacity for understanding. This is a purely formal utility, unrelated to the content itself, meant as preparation for the responsibilities, especially political, of adult life. From this perspective, it becomes clear that education in these subjects should be time-limited. Xenophon, unlike Isocrates, imposed not only temporal but also content-based restrictions, warning that both astronomy and geometry could consume a man’s entire life, leaving no room for other useful studies (Memorabilia IV.7.3, 5).

Ultimately, the views of Xenophon and Isocrates would prevail: scientific disciplines were permitted within general education only on the condition that their content be simplified or that instruction focus solely on formal training.

This educational stance intersected with a broader epistemological issue also evident in medicine: who could judge the competence of specialists? This question ties back to the earlier concern – how far must one go in learning these now complex and specialized fields? That only a specialist could judge another in the same domain (e.g., only a physician can assess a physician) was taken as axiomatic. Plato makes this point clearly: only a fellow specialist (homótechnos) can be a true judge (Charmides 171a4–c2; Ion 531d–e).

Nevertheless, elsewhere Plato acknowledges that a non-specialist may competently judge technical work – provided he possesses a superior kind of knowledge: either as a user who understands the function of the product, or as an architéktün who oversees and guides the work of specialists without directly practicing their craft. In the Laws, Plato affirms the general value of mathematical study but confines the pursuit of precise knowledge (akríbeia) to a few specialists (VII, 818a1–7). Similarly, in Politics (VIII.2, 1337a–b), Aristotle echoes this view.

Also in the Laws, Plato identifies polymathía – not mathematical ignorance – as the greater evil (VII, 819a3–6). This theme is developed further in a dialogue attributed to Plato but likely composed within the Academy, the Anterastaí, which argues that philosophy cannot consist in polymathía, even if confined to the téchnai deemed appropriate for a free man. It is not enough to avoid specialist-level precision, or to ensure learning does not crowd out other pursuits, as Xenophon had advised. The goal is to “follow the speech of the craftsman (dämiourgós) better than others present,” and to contribute meaningfully to the discourse – thereby demonstrating a superior understanding of technical knowledge without being a practitioner oneself.

These constraints address the objection that one person cannot master even two téchnai simultaneously – but not the objection that a polymath-philosopher resembles a pentathlete, always outperformed by specialists in each event (135b–136d). Intriguingly, in the early imperial period, Thrasyllus identified the anonymous interlocutor who advocated this philosophical polymathía with Democritus, a “true pentathlete” of philosophy and science (Diogenes Laertius IX.37).

In every case, this figure represents the ideal of the cultured free man, someone who acquires general knowledge of the sciences without becoming a specialist. This is the figure of the pepaideuménos – the educated man – who also appears in Aristotle’s writings. Alongside the practitioner, who exercises a craft, and the architéktün, who supervises it, Aristotle introduces, especially when discussing candidates for public office, a third type: one who possesses broad cultural knowledge of “virtually all the téchnai,” and who can thus pass sound judgment (krínein) on the words and actions of specialists – just as well as the specialists themselves (Politics III.11, 1281b 38–1282a 12).

From De Partibus Animalium (I.1, 639a1–16), we may infer that this judgment does not concern the truth of the content, which remains the specialist’s domain, but rather the logic and structure of the demonstration. In this respect, the pepaideuménos in Aristotle has been likened to the dialectician.

The issue of the relationship between scientific disciplines first emerged internally, within each of them, as a matter of methodological necessity. Later, in classical Greece, it developed further as these disciplines were gradually integrated into the broader framework of general paideía. This gave rise to the question of whether the various disciplines should simply be placed side by side – unified only by an overarching educational or cultural aim, as seen in the perspectives of Xenophon, Isocrates, and others – or whether there existed conceptual and methodological interconnections among them.

In Plato’s depiction, Hippias presents the various disciplines as discrete portions of a unified body of knowledge, without indicating any internal connections among them. The first to raise the issue explicitly were again the physicians – not only to define their relationship with other fields of knowledge, but also to establish clear boundaries from what they regarded as speculative or unfounded knowledge. The association between physician and soothsayer, for example, must have been long-standing, as both professions shared a predictive dimension based on the interpretation of signs. Aeschylus already refers, in mythological terms, to the figure of the iatrómantis, the physician-seer (Supplices 260–270).

Some Hippocratic physicians sought to distance medicine from divination and magical practices. The best-known case is the author of De morbo sacro, but even Sophocles deemed it inappropriate for a true physician to engage in therapy through incantations (Ajax 581–2). At the same time, other Hippocratic texts, drawing on ancient notions of the relationship between disease, climate, and seasonal variation (Iliad XXII, 30–31; Pindar, Pythian III, 47–50), asserted that knowledge of celestial, meteorological, and climatic phenomena was essential to medical theory and practice.

This view is succinctly expressed in De aëre, aquis, locis, where the author claims that “astronomy contributes no little to medicine” – the earliest known usage of the term ‘astronomy’ alongside its appearance in Clouds. A similar focus on calendars and meteorological patterns is found in the Prognosticus, which underscores the difficulty of calculating critical days, since even the months and the year could not be expressed in whole days. Likewise, Epidemics I.23 stresses the need to consider celestial phenomena and their specific manifestations in each locality to understand the distinct characteristics of diseases.

This expansion of medicine into adjacent areas of inquiry – ones that, strictly speaking, lay outside its immediate domain – could lead, if taken to the extreme, to the view that medicine should be grounded in a general understanding of human nature, or even of the universe. This position is explicitly rejected by the author of On Ancient medicine, who asserts that medicine cannot be founded on general theses, or ‘hypotheses,’ which are only appropriate to the study of metéüra and “things underground,” that is, phenomena opaque to direct perception (1.1–3; 20.1–2). In this way, a decisive boundary is drawn, asserting the autonomy of medicine as a discipline based on specialized knowledge, immune to external contamination. In this respect, the pluralism characteristic of ancient medicine is reaffirmed.

The issue of interconnections, however, did not remain confined to medicine. The earliest maps, beginning with the one attributed to Anaximander, must have involved geometric figures and concepts. Ancient sources often describe figures such as Meton or Enopides of Chios – credited with certain geometric discoveries – as having pursued geometry to solve astronomical problems. Indeed, the link between geometry (especially spherical geometry) and astronomy remained a fixture of ancient mathematical thought, reaching a climax in the work of Eudoxus of Cnidus. His theory of homocentric spheres, developed to account for the planets’ circular and seemingly irregular motions around the Earth, exemplifies this synergy.

Similarly, the realization that certain arithmetic problems – such as the incommensurability of magnitudes – could not be solved numerically but only geometrically, drew attention to both the distinctions and commonalities between arithmetic and geometry. A case in point is Hippocrates of Chios’ reformulation of the problem of cube duplication: since a numerical solution was unavailable due to the limitations of Greek numeration, he reframed it geometrically, as the search for two mean proportionals in continuous proportion.

Plato refers to Theodorus of Cyrene as “the geometer,” while also crediting him with teaching not only geometry but also astronomy, harmony, and arithmetic (Theaetetus 145c 7–d 3; 161e 4–7; 164e 7–165a 3). These same competencies are attributed to his student Theaetetus (145a 1–9). Thus, by the fourth century BCE, the case of Hippias no longer appeared exceptional: the mathematical disciplines increasingly formed a coherent whole.

At an indeterminate point in the early fourth century, the Pythagorean Archytas of Tarentum referred to a group of individuals who devoted themselves to the mathémata, achieving clarity in their knowledge of stellar motion, celestial phenomena, planar and spherical geometry, arithmetic, and music. “These disciplines (mathémata) seem to be sisters,” Archytas declared, “because they concern the two very first forms of being, which are themselves sisters” (DK 47 B 1). Although the authenticity of this fragment has long been debated, recent scholarship has leaned in its favor, even if the exact meaning of the ‘forms’ in question remains uncertain, and thus the precise nature of the relationships among the disciplines remains opaque.

In any case, it is well established that the fields listed by Archytas were not regarded as the domain of different specialists, but rather as objects of inquiry for a single community of scholars. It is unclear whether these were the individuals designated in Pythagorean circles as ‘mathematicians,’ as opposed to the ‘acusmatics’ – those who merely listened to the teachings.

At the beginning of another fragment attributed to Archytas – whose authenticity, like others, has also been questioned (DK 47 B 4) – it is stated that logistics, in relation to wisdom, appears to be far superior to other téchnai, as it is capable of addressing geometrical matters more clearly than geometry itself. Today, we generally interpret logistics as the technique of calculation using natural numbers. If this were Archytas’ intended meaning, it would be difficult to understand how he could have maintained the superiority of geometry over arithmetic, given the Pythagorean discovery of incommensurable magnitudes.

This primacy of geometry is recognized by Plutarch (Quaestiones conviviales VIII.2.1, 718e; DK 44 A 7a), who attributes to Philolaus of Croton – another Pythagorean, predating Archytas – the statement that “geometry is the principle and metropolis of the others (probably the mathémata).” This can be understood as either establishing geometry as the model for the other mathematical disciplines or as identifying it as the foundational core from which they all stem, like colonies from a mother city.

However, it is also possible that Archytas, by logistics, meant not simply numerical computation, but rather the domain of lógoi – that is, of ratios – and thus a theory of proportions. This would explain how logistics could realize the full potential of geometric problem-solving and serve as the conceptual bridge uniting the disciplines listed in Fragment 1, since ratios and proportions also feature prominently in arithmetic, music, and astronomy.

It is worth noting that, according to Diogenes Laërtius (VIII.83), Archytas was also the first to systematically investigate mechanics using mathematical principles, thereby extending mathematical knowledge to include mechanics as well.

This accumulation of competencies across various fields seems to stand in contrast to the principle – repeatedly stated by Plato and Aristotle – that each person is best suited to master only one art. In the case of the mathematical sciences – and, according to Aristotle, also in natural philosophy – both thinkers ultimately made exceptions, accepting the idea that a single individual could achieve proficiency in multiple disciplines.

However, the division between productive-manual crafts and theoretical sciences remained firmly in place: what was held to be necessary in the realm of manual labor did not extend to the theoretical sphere. These exceptions rested on another dichotomy as well – that between professional, remunerated knowledge and knowledge pursued either disinterestedly or for educational purposes. The sciences, in this view, could coexist and complement one another within a general paideía, the precursor to what would later be termed enkìklios paideía.

The key issue thus became identifying the criteria that would justify and regulate this coexistence. From the analysis of actual or desired relationships among the scientific disciplines arose the earliest attempts at a classification of the sciences.

It is at this point that Plato’s Republic, especially Books VI and VII, becomes central. There, Plato outlines the five major mathémata to be practiced (gymnázein) by the future rulers of the city: arithmetic and calculation, plane geometry, stereometry, astronomy, and music. His discourse is prescriptive rather than descriptive; it opposes not only popular opinion, but also the prevailing attitudes and practices of contemporary mathematicians.

Within this normative framework, Plato also addresses the interrelatedness of the sciences: “Just as the eyes were made for astronomy, so the ears were made for harmonic motion; and these sciences (epistæmai) are sisters (adelphaí), as the Pythagoreans say” (Respublica VII, 530d 6–9). This passage is often linked to the aforementioned fragment of Archytas, though some commentators reject the connection, citing two main differences: (1) Plato names only astronomy and harmonics as ‘sisters,’ whereas Archytas also includes arithmetic, geometry, and possibly stereometry (which he refers to as spherical); and (2) the sequence in which the disciplines appear differs.

With respect to the first point, another passage in the Republic (VI, 511b 1–2) features Glaucon, Plato’s brother, referring to geometry and “the arts that are its sisters,” suggesting a more widespread notion. In general, Plato seems to view all five disciplines as mutually related. As for the sequence, it is not, in itself, sufficient to deny the possibility that Plato had Archytas in mind – especially since we do not know what ordering principle Archytas followed.

This does not mean that Plato’s view is reducible to that of Archytas; the differences between them must be located elsewhere. One such distinction appears in Republic VII, 530b–531b, where Plato criticizes the Pythagoreans for wasting time on sensible things in their investigations. Crucially, Plato does not establish a hierarchy among the mathematical sciences in the manner of Philolaus or Archytas. Instead, he posits a hierarchy between the ensemble of the five disciplines and dialectic, which is described as their ‘summit’ and ‘crown’ (534e 2–3).

Concerning the five disciplines, Plato writes that we often call them epistæmai – sciences – merely by convention (éthos) (533d 4–5), though it would be more accurate to refer to them as homología – agreement or convention – since they do not question or justify their first principles, but take them as self-evident (533c 1–5). This is the earliest known passage in which the term epistémä is applied to mathematics, though its context is pedagogical.

For Plato, as for Isocrates, mathematics serves as a form of mental training. Unlike Isocrates, however, Plato also considers it content-wise preparatory for dialectic, guiding the soul toward intelligible reality. Against traditional instruction, he proposes a new model in which these disciplines are cultivated as preparation for philosophical inquiry. This pedagogical aim applies both to each individual discipline and to the set as a whole. For example, one should study logistics “not as a layman (idiütikõs), but in such a way as to come, by reasoning, to contemplate the nature of number – not for buying and selling” (VII, 525c 1–3).

Elsewhere, Plato clarifies that the goal of studying all these sciences is to uncover their interrelations, their koinünían and syngéneian – their shared community and kinship (531c 9–d 4). Those in their twenties who have passed prior pedagogical stages are reintroduced to these disciplines, which they had learned earlier in bulk, “so that they may gain a comprehensive vision of the kinship among them” (537b 8–c 3). This confirms that, like Archytas, Plato conceived of all these sciences as related, though the recognition of their interconnectedness was not assumed, but presented as a goal of advanced education.

That this notion of scientific propaedeutics had cultural resonance is suggested by a parody from the New Comedy poet Nicomachus, who listed astronomy, geometry, medicine, and number as preparatory subjects – for cooking (Athenaeus VII, 290e–291d).

One final question remains: why did Plato arrange these disciplines in this particular order? The answer may lie in pedagogical concerns – beginning with the easiest subjects and proceeding to the most difficult – or perhaps in deeper structural reasons. Arithmetic and logistics come first because they constitute the common foundation “of which all téchnai, all intellectual processes, all sciences make use, and which everyone must learn first” (Respublica VII, 522c 1–3; Philebus 55d 1–56c 4). This suggests a precise correspondence between the objective structure of knowledge and the order of learning.

After arithmetic comes geometry, though Plato does not explicitly justify the sequence. He does, however, specify that stereometry – the geometry of solid figures – must follow plane geometry, as the third dimension logically succeeds the second (528b 1–3). Astronomy, as the “motion of solids” (528d 11–e 1), must then build on stereometry; here, Plato may have drawn inspiration from the geometrical astronomy of Eudoxus.

There still remains the question of the relationship between astronomy and harmony, particularly in light of the influence the Pythagoreans may have exerted on Plato. In the Republic, it is not explicitly stated that the study of harmonic relations depends upon, or is grounded in, the study of astronomy. Rather, what Plato suggests is a parallelism between the two domains: “just as the eyes were made for astronomy, so the ears were made for harmonic motion.” In this passage, the term ‘sisters’ should be interpreted literally: these are not sciences derivable from one another, but rather stand side by side, occupying parallel planes as siblings. Both, in fact, deal with a form of motion, each serving as the antístrophon – the complementary or counterpoint – of the other, the “responses” (Respublica 530c 11–d 10). Furthermore, both are called upon to seek out numerical relationships not within the sensory phenomena that reach the eyes and ears, but rather in the numerical ratios that underlie them (531b 7–c 4).

From this perspective, it could be argued that underlying both astronomy and harmonic science is the more fundamental science of numbers and proportions. This conceptual foundation would justify not only the priority assigned to arithmetic within the mathematical curriculum, but also the elevation of astronomy – and, by analogy, harmony – to the status of the most complex and culminating sciences within the hierarchy of mathematical knowledge.

Along these lines is the Epinomis, a dialogue already attributed in antiquity to Philip of Opus, a student of Plato. After distinguishing true and proper sciences (epistaí) from the arts deemed unworthy of a free citizen – such as divination and medicine – the dialogue asserts that true wisdom is secured solely through the knowledge of number. Number, it argues, derives its origin from astronomical observation, but at the same time constitutes one of the preliminary mathémata, together with geometry and stereometry (on which the study of rhythm and harmony depends), leading to the culmination of knowledge represented by mathematical astronomy. As already argued in the Republic, the study of the various disciplines is meant to reveal the existence of a natural bond (desmós) linking them all (991d 8–992a 1).

Speusippus, Plato’s successor as head of the Academy, appears to have shared this concern; according to Diogenes Laertius (IV.2), he was the first to investigate what the mathémata had in common in order to establish mutual kinship among them. While this assertion of priority lacks solid foundation, it does attest to the centrality of the issue within the Academy. In the Hellenistic age, Eratosthenes of Cyrene identified the bond mentioned in the Epinomis with the theory of proportions, while the Neoplatonist Proclus preferred to see it in the axioms or principles common to all mathematical sciences. Proclus’s interpretation, however, presupposes the Aristotelian theory of science as demonstrative knowledge – whose most brilliant expression is found in Euclid’s Elements – and indeed, Aristotle may be viewed as the final link in a fourth-century BCE discussion concerning the interrelations among the sciences.

Aristotle acknowledges the autonomy acquired by the individual sciences and, in the Posterior Analytics, states that each science builds its demonstrations upon its own principles, appropriate to the kind of entities it studies. Hence, the prohibition against one science intruding into the domain of another – the principle Aristotle calls metábasis eis állo génos. This means, for example, that it is not permissible to prove geometrical propositions using arithmetic, or vice versa (Posterior Analytics I.7, 75a 36–39). Similarly, a clear line separates mathematical disciplines from physics: mathematics abstracts certain properties of bodies without regard for their physical aspects, while physics must concern itself with phìsis, which always acts with an end in view (Physics II, 193b 22–35; De Partibus Animalium I.1, 641b 11–12).

Nevertheless, Aristotle’s own writings include procedures that seem to contravene these prohibitions. He undertakes interdisciplinary investigations – for instance, in De Motu Animalium, where he shows how the motion of the heavens is a general condition for animal motion, and conversely, how studying animal motion can correct certain mathematical assumptions found in De Caelo. Biological inquiries, falling within what Aristotle calls ‘physics’ or the science of nature, may thus intersect with astronomical studies; but this serves a heuristic purpose and does not violate the general principle of disciplinary distinction. In this spirit, Aristotle argues that the physicist may investigate the general principles and causes of health and disease – on which both natural philosophers and philosophically inclined physicians converge (De Sensu et Sensibili 436a 27–b1; De Respiratione 480b 22–30).

Aristotle also recognizes a hierarchy among the mathematical sciences, determined by their respective degrees of exactness (akríbeia). He offers several criteria for this: for example, whether a science deals not only with observed data but also with causes, or whether it begins from fewer assumptions – as with arithmetic, compared to geometry, which must assume the “position” of the entities it considers (Posterior Analytics I.27, 87a 31–37). These criteria of exactness do not fully coincide with the Platonic criterion from the Philebus, which emphasizes a science’s relative distance from the sensible world. Nonetheless, Aristotle sometimes describes the hierarchy among sciences as a relation of subordination: some disciplines, such as optics, harmonics, and astronomy, are “more physical” than geometry or arithmetic. Thus, geometry studies a physical line in abstraction, not as physical, while optics studies it as physical (Physics II.2, 194a 7–12). Optics, then, takes certain geometrical propositions as premises for its own demonstrations. The same holds for the relationship between harmonics and arithmetic, or between mechanics and stereometry.

Optics, harmonics, and mechanics may be regarded as sciences that ascertain phenomena, whereas their corresponding higher-level sciences – geometry, arithmetic, and stereometry – are sciences that demonstrate the causes of those phenomena (Posterior Analytics I.9, 76a 22–25; I.13, 78b 34–79a 6). These subordinate relationships occur not only within mathematics but also in connections between mathematical disciplines and inquiries belonging to physics or medicine. For example, medicine observes that circular wounds heal more slowly, but it is the geometer who, by studying the ratio between area and perimeter, explains why. One must therefore speak of triads of disciplines, each comprising an observational, a demonstrative, and a higher-level explanatory science. For instance, while the physicist identifies the phenomenon of the rainbow, it is the optician’s task to provide a theoretical explanation (Posterior Analytics I.7, 76a 10–16); in fact, Aristotle’s Meteorology offers a geometrically structured account of the rainbow. A similar triadic relationship holds between acoustics (the study of physical sounds), harmonics, and arithmetic. These Aristotelian reflections clearly indicate that by the second half of the fourth century BCE, a well-structured complex of sciences had developed – one in which problems of disciplinary boundaries and mutual relationships were actively addressed.

Giuseppe Cambiano

References

- Burkert 1972: Burkert, Walter. Lore and Science in Ancient Pythagoreanism. Cambridge (Mass.): Harvard University Press, 1972. (Engl. rev. ed. of: Weisheit und Wissenschaft. Studien zu Pythagoras, Philolaus und Platon. Nürnberg: H. Carl, 1962).

- Cambiano 1971: Cambiano, Giuseppe. Platone e le tecniche. Torino: Einaudi, 1971. (Nuova ed. riv. e aggiornata: Roma-Bari: Laterza, 1991).

- Cavallo 1988: Cavallo, Gugliemo (ed.). Le biblioteche nel mondo antico e medievale. Roma-Bari: Laterza, 1988.

- Derenne 1930: Derenne, Eudore. Les procès d’impiété intentés aux philosophes à Athènes au Ve et au IVe siècles avant J.-C. Liège: Imprimerie H. Vaillant-Carmanne; Paris: Champion, 1930.

- Detienne 1967: Detienne, Marcel. Les maîtres de vérité dans la Grèce archaïque. Paris: F. Maspero, 1967.

- — 1988: Les savoirs de l’écriture en Grèce ancienne. Villeneuve-d’Ascq: Presses Universitaires de Lille, 1988.

- Dicks 1970: Dicks, D.R. Early Greek Astronomy to Aristotle. London: Thames & Hudson, 1970.

- Edelstein 1967: Edelstein, Ludwig. Ancient Medicine: Selected Papers. Edited by Owsei Temkin and Clarice Lilian Temkin. Baltimore (Md.): The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1967.

- van der Eijk 1995: van der Eijk, Philip J., H.F.J. Horstmanshoff, and P.H. Schrijvers (eds.). Ancient Medicine in Its Socio-Cultural Context: Papers Read at the Congress Held at Leiden University, 13–15 April 1992. Amsterdam-Atlanta: Rodopi, 1995. 2 vols.

- Gladigow 1965: Gladigow, Burkhard. Sophia und Kosmos: Untersuchungen zur Frühgeschichte von Sophos und Sophie. Hildesheim: G. Olms, 1965.

- Hadot 1984: Hadot, Ilsetraut. Arts libéraux et philosophie dans la pensée antique. Paris: Études augustiniennes, 1984.

- Havelock 1963: Havelock, Eric Alfred. Preface to Plato. Cambridge (Mass.): Belknap Press, Harvard University Press, 1963.

- Kudlien 1967: Kudlien, Fridolf. Der Beginn des medizinischen Denkens bei den Griechen: Von Homer bis Hippokrates. Zürich-Stuttgart: Artemis Verlag, 1967.

- — 1968: Die Sklaven in der griechischen Medizin der klassischen und hellenistischen Zeit. Wiesbaden: Steiner, 1968.

- Lloyd 1966: Lloyd, Geoffrey Ernest Richard. Polarity and Analogy: Two Types of Argumentation in Early Greek Thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1966.

- — 1979: Magic, Reason, and Experience: Studies in the Origin and Development of Greek Science. Cambridge-New York: Cambridge University Press, 1979.

- — 1987: The Revolutions of Wisdom: Studies in the Claims and Practice of Ancient Greek Science. Berkeley (Calif.): University of California Press, 1987.

- — 1991: Methods and Problems in Greek Science. Cambridge-New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

- Snell 1924: Snell, Bruno. Die Ausdrücke für den Begriff des Wissens in der vorplatonischen Philosophie. Berlin: Weidmann, 1924.

- Vernant 1974: Vernant, Jean-Pierre [et al.]. Divination et rationalité. Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1974.