In Book I of the Metaphysics, Aristotle traces a historical excursus on earlier philosophical doctrines, proposing various criteria for their identification – geographical origin being among the most prominent. Ionian philosophy, represented by the Milesians Thales, Anaximander, and Anaximenes, as well as Heraclitus of Ephesus, was succeeded by Italic philosophy (Pythagoreans, Eleatics, and Empedocles), in line with the shifts in Greek colonial expansion after the fall of Miletus in 494 BCE. Philosophy entered Athens later, with Anaxagoras, who came from the coast of Asia Minor, and Archelaus. However, the figures of the atomists – Leucippus, likely residing in Elea, and Democritus – remain isolated.

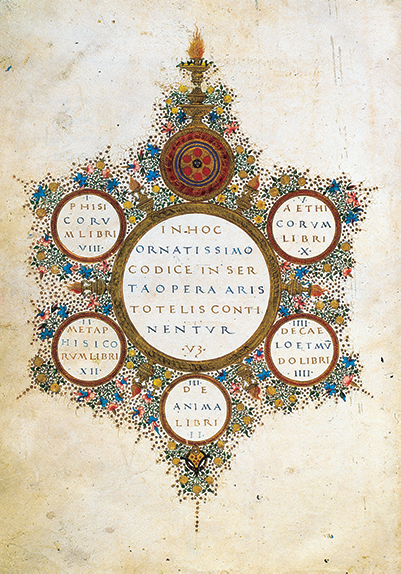

Due to the frequent absence of works definitively attributable to these authors, and the abundance of circulating information among ancient scholars, H. Diels, in the latter half of the nineteenth century, found it expedient to rely on the doxographical tradition dating back to Theophrastus and, ultimately, Aristotle. This led, in the early twentieth century, to the compilation of a systematic edition of the fragments of and about the pre-Socratics, culminating in the 1951 revision by W. Kranz. Although the aim was to consolidate the various lists of authors and doctrines – expanded by later discoveries of quotations and testimonies – the result was a rigid periodization of philosophical history, anchored in the historiographical category of the ‘pre-Socratics.’ By distinguishing explicit quotations from testimonies for each author, the Diels-Kranz edition adopted a dry thematic structure that created a stark contrast between philosophy before and after Socrates, as though a fundamental shift had occurred in content and methodology. Aristotle justified this change by asserting that, following Socrates, knowledge could no longer be advanced without the mediation of conceptual thought (De partibus animalium I, 642a 25; Metaphysica I, 987b 1-6).

In the standard historiographical model, inquiry into Nature was supplanted by inquiry into man and his civic environment, the pólis. While this model tends to characterize pre-Socratic inquiry as naturalistic, such labeling might be incidental – possibly shaped by Aristotle’s selective portrayal of these thinkers. Especially since much of their thought has not survived in its original form but only in the form of isolated theses embedded within others’ arguments. Similarly, the supposed homogeneity among these thinkers – leading to the concept of pre-Socratic ‘schools’ – may stem from the structural logic of fragment anthologies: repeated, conventional titles; geographical and chronological inaccuracies due to doctrinal affinities; and invented journeys, encounters, or discipleships. Biographical data often appear insufficient to contain the conceptual content that insists on surfacing. All of this reinforces the perception that authentic, mature philosophical figures are post-Socratic, enjoying autonomy and originality – either substantiated by extant works or, like Socrates, supported by competent official biographers.

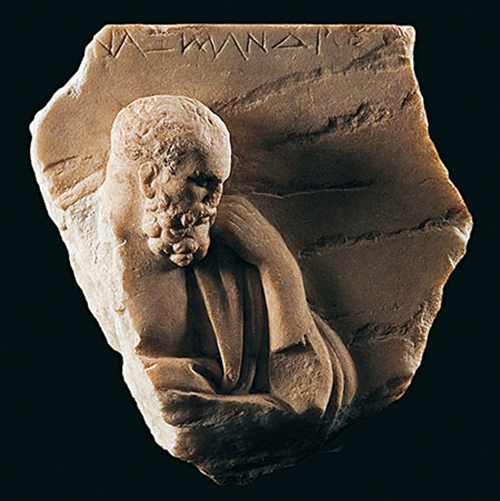

Among those whose legacy is preserved mainly through reputation is Thales (624/623–548/545 BCE), universally called ‘the first’ by doxographers. He is credited with naturalistic investigations conducted without mythological or fatalistic elements. He allegedly posited water as the proto-element, the internal constitutive principle of all things (DK 11 A 1, 3, 12, 13, 23); applied geometry and mathematical calculation to measure the height of pyramids and the distance of ships at sea (DK 11 A 1, 20, 21); and predicted an eclipse (DK 11 A 1, 2, 3, 5, 13c, 17, 18, 19). He is also said to have fallen into a well while walking and observing the stars (DK 11 A 9). This anecdote, reported by many sources starting with Plato (Theaetetus 174a), seems to encapsulate numerous doctrines attributed to him. Astronomical observation was indeed conducted from within wells, where water at the bottom reflected portions of the sky, facilitating the study and measurement of stellar movements – perhaps even the eclipse observation so central to tales about him. Certainly, legends were woven around his figure, and some attributions appear designed to portray him as a foundational figure – such as the one, reported by Diogenes Laertius (likely mid-3rd century CE), which credits him with establishing the calendar by fixing the seasons and dividing the year into 365 days (DK 11 A 1).

As for Anaximander (610–547 BCE), only one significant fragment survives. Simplicius, the source, refers to an infinite Nature (phìsin ápeiron) taken by Anaximander as the first principle, and then quotes: “from whence indeed beings originate, there they also perish according to necessity (katà tò chreón); for they pay to each other the penalty (díkän) and atonement (tísin) for injustice (adikías) according to the order of time (katà tèn toú chrónou táxin)” (DK 12 B 1).

The use of juridical terms has led to the interpretation that time functions as a divine agent marking, within the Infinite, the genesis and dissolution of organized systems. Three doxographers – Plutarch (DK 12 A 10), Hippolytus (DK 12 A 11), and Simplicius (DK 12 A 9) – offer consistent if varied accounts of how this process occurs, what the Infinite consists of, and how beings are structured. Anaximander, placing the eternal and immutable Infinite above any material element, posited that motion arises within it, by which beings are separated. This eternal motion enacts the decree of time, producing the heavens (ouranoús) and their configuration. The first distinction to emerge is that between hot and cold, leading to the arrangement of elements in the Cosmos: an external sphere of flame, then, in concentric rings, the various heavens – those of the Sun, Moon, and stars – and the Earth, around which air wraps like the bark of a tree. The shape of the Earth remains uncertain based on the scant evidence. Yet the bark metaphor suggests the cross-section of a tree trunk, aligning with the fragment that describes the Earth as “resembling the trunk of a column” (DK 12 B 5). Hippolytus (DK 12 A 11), in the cited passage, adds that the Earth has “a curved (gyrón) spherical form, resembling a stone column,” with only one inhabited side; it floats unsupported, equidistant from all points. However, careful lexical analysis of the sources indicates that the terms ‘sphere’ and ‘spherical,’ though frequent, are likely later interpolations – especially by Diogenes Laertius (DK 12 A 1).

Adhering to the description of the Earth as drum-shaped, the discovery attributed to Anaximander of the use of the gnomon (DK 12 A 4) – whose operation presumes a spherical Earth, given the assumption of parallel sun rays – appears incompatible. To resolve this contradiction, it would be sufficient to posit a significantly closer position of the Sun and to adopt the opposite hypothesis: that the sun’s rays reach the Earth’s surface in a divergent manner. This would allow gnomonic data to be interpreted even under the assumption of a flat Earth. In the absence of control texts, scholars have been compelled to rely on interpretation. Some have even proposed that the Earth’s shape was neither flat nor spherical, but concave – such being the meaning of the term gyrós, with which Diels corrected the translated hyrgos.

This hypothesis also impacts the attribution to Anaximander of the first map of the inhabited Earth (DK 12 A 6). The source, cited by Agathemerus, is the geographer Eratosthenes, who claims that Anaximander collaborated with Hecataeus of Miletus to refine the map for practical use. This proposition, however, was met with skepticism by Herodotus, who found the schematic geometrization of the ecumene ineffective for orientation. Indeed, he recounts an episode involving Aristagoras of Miletus and his failed attempt to convince Cleomenes, king of Sparta, to liberate Ionia from Persian rule by using such a map (Histories, V, 36, 49–54). For the representation of territories or journeys, the most reliable tools remained, for a long time, periploi and itineraries composed by logographers. A geographical depiction (pínax) could only become effective through the accumulation and exchange of experience among scholars, and access to a broad corpus of navigational data – information passed down through generations of voyages. This was necessary not only for depicting, but also for verifying geographic knowledge beyond the draftsman’s direct observation.

Such a context was made possible in the Library of Alexandria, where Eratosthenes himself served as director. In contrast, the reclusive Anaximander of Miletus, drawing upon his astronomical knowledge, may have conceived a representation of the entire ecumene as a continuation of his cosmic map – an early global model encompassing the Earth’s regions, the circles of the stars, the Moon, and the Sun, with the aim of enclosing his geometric kósmos within a single image that modernized the mythical ouranós. This hypothesis does not stem from direct Anaximandrian accounts, but rather from a Mesopotamian clay tablet preserved in the British Museum, which depicts a Babylonian mythological cosmos. The transmitter of such representations to the Greek world may have been Pherecydes of Syros, a contemporary of Thales, who located the wedding gift exchange between Zas and Cthonie within a similar cosmographic landscape (DK 7 B 2). The world shown in the Babylonian map exhibits similarities not only with Pherecydes’s conception, but also with that of Anaximander: it is circular, surrounded by the Amaro River, and generally flat, though enclosed by mountain ranges – mythological, inaccessible peaks that obstruct the Sun’s view. This is a concave depiction of the Earth’s surface, implying that Anaximander should not be credited with the discovery of the ecliptic (DK 12 A 5). Rather, his model correctly describes the inclination of the Sun’s diurnal path, which, during the night, would merely move beyond the bounding mountains of the terrestrial disk.

The absence of corroborating Anaximandrian texts is oddly compensated by Anaximenes’s conception of the cosmos, where the stars do not pass beneath the flat, air-supported Earth, but instead revolve around its outer edge – like spinning a cap around one’s head. The Sun, in this view, disappears not by moving to the opposite hemisphere but because its path leads it behind the Earth’s highest elevations (DK 13 A 7 and 14).

Regarding the figure of the third philosopher from Miletus, Anaximenes, neither sufficient nor unequivocal doxographical evidence exists – whether for the dates of his birth and death or for his discipleship, which some sources attribute to Anaximander and others to Parmenides (DK 13 A 1 and 2). Aristotle echoes this uncertainty in De caelo, where he discusses the view held by those who claim that the Earth is flat and shaped like a drum. Their argument is that the Sun, at both rising and setting, appears to be obscured by the Earth along a straight rather than a curved line; for if the Earth were spherical, the line along which it eclipses the Sun should also be curved. However, they fail to consider the distance between the Sun and Earth, and the extent of the Earth’s circumference (De caelo II, 294a 1–7).

Similar difficulties emerge when attempting to define the intellectual profile of Heraclitus (6th–5th century BCE), about whom we possess a substantial number of testimonies, though these in turn give rise to considerable problems. His cryptic and allusive language, which makes his doctrine difficult to access, earned him the epithet ‘the Obscure,’ inviting hermeneutic manipulation in part due to the evocative force of his expression, which many found provocatively stimulating. Unlike with Thales, the complexity of reconstructing Heraclitus’s thought stems paradoxically from the overabundance of fragments. The sources are highly diverse: in addition to standard doxographers such as Plutarch, Aetius (1st–2nd century CE), Sextus Empiricus (c. 140/160–220/230), Hippolytus, and Diogenes Laërtius, we also find witnesses from distinct cultural milieus – such as Marcus Aurelius (121–180) and Clement of Alexandria (c. 145/150–211/217) – a clear indication that his pithy language continued to captivate readers across centuries.

Empedocles (5th century BCE) presents another unresolved case; the surviving texts do not contradict Aristotle’s reports, yet they underscore their incompleteness. While the naturalistic doctrines attributed to him in Aristotelian texts are indeed confirmed in his poem On Nature, Empedocles appears to go much further in another work, On Purifications, where he describes the journey of souls to the underworld, a “covered cavern” (DK 31 B 120), “where Murder and Wrath and other generations of Ruin / Arid Diseases, Decay and the fluids they produce / flow in darkness through Ate’s meadows” (DK 31 B 121). The law governing this realm is different:

It is Necessity’s vaticinium, ancient decree of the gods /

and eternal, sealed by vast oaths: /

if anyone criminally defiles his hands with a crime /

or if anyone by Contention has sinned by swearing a false oath, /

the daemons who have been blessed with a long life /

wander for thirty thousand seasons far from the blessed /

being born in every form of mortal creature over time, /

changing the painful paths of life. /

The rush of the aether indeed thrusts them into the sea, /

the sea tosses them back to the soil of the Earth, the Earth into the rays /

of the shining Sun, which in turn tosses them into the aether’s whirlpools; /

each receives them from another, and all hate them. /

I too am one of these, exiled from the divine and wandering, /

for trusting in raging Contention. (DK 31 B 115)

This doctrine of metempsychosis is inspired by a passage from Hesiod’s Theogony, which describes how a perjured god is excluded from the blessed realm and “lies breathless” upon the waters of the Styx for a year (Theogony 775–806). In Empedocles, however, punishment is no longer breathless but enacted through reincarnation: the divine souls are condemned to inhabit vegetal, animal, and ultimately human bodies. Nor is Empedocles himself exempt from this process; he confesses: “I was once already a boy and a girl, / a shrub, a bird, and a silent fish leaping from the sea” (DK 31 B 117). In this journey through different levels of existence, a form of divine conviviality may occur, at least for some: “Dwelling among the other immortals, eating / no longer of human grief, indestructible.” (DK 31 B 147).

This blissful condition appears as a kind of apprenticeship for elites, but not exclusively: “Eventually, soothsayers, poets, and physicians / and rulers become of the men who dwell on Earth, / whence gods, worthy of reverence, are reborn.” (DK 31 B 146). Such transformation takes place beyond ordinary human life and, since it is among mortals that the gods must be reborn, it suggests an ongoing exchange between realms of existence, as described in On Nature: “Each predominates in turn in the cyclical return, / perishing into and arising from one another in the vicissitudes of fate.” (DK 31 B 26). The sovereignty of Nature’s generative cycle is absolute and extends even to the divine: “And how many immortal forms there are / […] in Wrath they are all divided in form and apart, / but in Harmony they come together and desire one another. / And from these, indeed, all things that were, are, and will be have sprung – / trees, men and women, / animals, birds, and aquatic creatures, / and the long-lived gods, most honored.” (DK 31 B 21)

This vision of divine conviviality as a formative stage for rulers or as a precondition for divine rebirth aligns with Plato’s doctrine of the soul’s immortality – recognized by scholars as an Orphic inheritance developed in the Pythagorean school, absorbed by Empedocles and later echoed in various Platonic dialogues. Aristotle, though surely aware of this doctrinal core, makes only a cursory mention of “Pythagorean myths” in the De anima (I, 407 b20–25). Likewise, in discussing Empedocles, he is careful to omit anything not strictly pertaining to the material transformation of natural entities. Thus, the pre-Socratic’s personality emerges in a mediated but not distorted form, supporting – albeit indirectly – the now-debated yet once widely accepted doxographical hypothesis of a dual literary production: Empedocles as both naturalist and shaman-like sage.

Theophrastus, who excerpted and integrated Aristotle’s chapters on pre-Socratic doctrines for use within the Lyceum. Aristotle is, indeed, the primary source on the pre-Socratics, but at the same time he is an unfaithful one: his interpretation, in attempting to penetrate and make sense of his predecessors’ theses, offers a partial perspective and flattens them chronologically, assimilating them into his own conceptual framework. What Aristotle provides can scarcely be called quotations, and often the personality of each author, as presented in the Aristotelian context, diverges significantly from the portrait inferred from other reliable sources or from the few surviving authentic fragments.

In effect, Aristotle reconstructed the history of philosophical thought using his own conceptual and linguistic categories. According to some scholars, his goal was to construct a historical narrative by presenting the most widely held opinions – opinions whose discussion could, through subtle dialectical maneuvering, lend support to his own positions. This approach ultimately had the effect of situating his predecessors and himself on a shared platform of philosophical debate, which, while not conducive to a historically accurate reading of earlier thought, likely enabled the initial identification of a philosophical tradition.

One would be hard pressed to find a rationale for grouping together the humorous anecdotes about Thales, the mysticism of the Pythagorean brotherhood, the enigmatic eloquence of Heraclitus, and the poetic inspiration of Parmenides on the topic of Being within a coherent doctrinal continuum – let alone to discern within them the roots of an emerging naturalistic interest. Yet Aristotle remains an indispensable interlocutor in our engagement with the pre-Socratics. His naturalistic perspective laid the groundwork for a complex discussion of cosmological issues, a task that Plato had not achieved with the same degree of systematization, by framing them within a specific ontological domain that can be defined as ‘nature’. Within this framework, Aristotle deployed categories such as ‘natural’ and ‘naturalism’, and he sketched out a methodological path for investigating the material causes of natural phenomena. It should be emphasized, however, that the naturalistic connotation attributed to this tradition of thought – which would become highly influential in later historiography – is in fact incidental. It is instrumental to the scope of inquiry developed in the Physics and Metaphysics, and it does not reappear in other works such as De anima.

Aristotle frames the cosmological question in its earliest formulation at Miletus as follows:

[...] on the question of whether there is one principle or many, and how many, and of what kind, there is no agreement. Thales, the initiator of this type of inquiry, maintained that it is water (hence his claim that the Earth floats on water), and perhaps this opinion was inspired by the observation that all things are nourished by moisture [...]. Indeed, some believe that even the most ancient thinkers – those who lived long before the present generation and were the first to speak in theological terms – held this view of Nature: for they represented Ocean and Tethys as the parents of becoming, and the oath of the gods as sworn by water [...]. Whether this view of Nature is truly primitive and ancient is uncertain; however, Thales is said to have expressed something of this sort concerning the first cause. As for Hippas, [...] Anaximenes and Diogenes, on the other hand, posited air as prior to water and as the fundamental principle of simple bodies.” (Metaphysica I, 983 b20-984a 7)

In Metaphysics, Aristotle thus refers to Thales as the first to identify water as the principle (arché), and immediately juxtaposes his account with myth. He notes that those who spoke in mythical terms had indicated the same principle when they “represented Ocean and Tethys as the parents of becoming (tæs genéseüs patéras)” (ibid., 983b 30-31). This reference to myth pertains to those who, remaining within that cultural and linguistic framework, claim to discern in ancient tales the same material entities now increasingly discussed in philosophical contexts. It is, in short, one interpretative path among many adopted by those who engage with myth, without precluding alternative readings. Aristotle’s intention, however, is to develop an inquiry grounded in naturalistic themes. The idealized sequence of developments and oppositions among the Milesians eventually outlines a concept of progress in naturalistic investigation – a model dear to Aristotle’s own philosophical project. His effort to interpret this ‘scattered’ and fragmentary body of knowledge aims to confer upon it a sense of completeness by integrating it into a unified research field. The passages on Thales in Metaphysics Book I illustrate this approach well: for instance, the claim that the Earth floats on water is presented, explained, and justified entirely through Aristotelian deductions.

Why, then, given this need for integration, does Aristotle begin with Thales rather than with more familiar figures such as Parmenides or Heraclitus, whose works and doctrines were better known? One answer might be that he sought to anchor his account in a recognized tradition of authority. Consequently, he could begin only with one of the Seven Sages, regarded as the putative founders of all that was esteemed and institutionalized in Greek culture. An alternative explanation involves Hippias, the sophist renowned for his prodigious memory, who had already compiled lists of notable events and figures and who, according to Diogenes Laërtius (DK 86 B 7), transmitted a thesis attributed to Thales. Hippias was also well known to Plato, who made him a character in his dialogues. It is speculated that one of Hippias’s catalogs may have served as a reference for Aristotle’s philosophical genealogy; if so, Aristotle’s role would shift from being the initiator of doxography to one of its more systematic continuators.

The close comparative reading of the pre-Socratics inevitably involves the application of inappropriate categories. Thus, Thales is designated as the archägós (the originator) of philosophy; Anaximenes and Diogenes maintain that air is málist’archén (‘more principle’) than water. One suspects that Aristotle’s goal is to present these thinkers as necessary stages culminating in his own naturalistic theory of the four causes – three of which, he claims, were already known to the pre-Socratics. The justifications for choosing one element over another, for instance, are Aristotelian interpolations, as is the very attribution of the term arché – all clear signs of a deliberate conceptual translation. To interpret Thales’s claim that the Earth floats on water, Aristotle proposes a comparison with myth and deduces a functional equivalence between the Ocean/Tethys pair and water itself, both conceived as the origin of becoming. In the reference to primal substances – a theme characteristic of Eastern cosmologies – Thales does not go beyond identifying water as a support. For this reason, Aristotle feels justified in applying the technical term arché to Thales’s water. To ensure that the appeal to the infinite does not undermine the search for a principle, Aristotle introduces Anaximander’s solution, in which the infinite (apeiron) is itself the principle (arché), insofar as it contains and envelops all (Physica III, 203b3).

Thus, applying the term arché to Thales’s cosmological thesis allows Aristotle to align the Milesian doctrines with other cosmologies, thereby enabling comparison between otherwise incommensurable principles. Taken in themselves – whether ‘water,’ ‘air,’ ‘infinite,’ or ‘number’ – these principles share nothing. The possibility of critical comparison arises only by translating them into a common conceptual category.

It has already been noted that, despite the various biases attributed to Aristotle, he must be credited with the intellectual honesty of acknowledging a philosophical development divergent from the path he ultimately pursued. Perhaps it is the very nature of the philosophical debate inaugurated by Plato – one to which the Stagirite remains deeply indebted – that prevents him from ignoring such fascinating antagonists: the “very ancient ones” who preferred to speak of Oceanus, of his union with Thetis, or, as certain philosophers did, of Love.

It seems to me that each of them tells us a myth, as if we were children. One [Pherecydes of Syros] says that there are three entities and that sometimes they clash with one another, while at other times, becoming friends, they engage in nuptials and bear children. Another [Archelaus] says there are two – the wet and the dry, or the hot and the cold – and that they cohabit and join in marriage. Our Eleatic lineage, however, which begins with Xenophanes and even earlier, convinced that what is called ‘all things’ is one being, recounts its myths accordingly. But some Muses of Ionia [Heraclitus], and later of Sicily [Empedocles], believed that the soundest position lay in combining both theses, asserting that being is both multiple and one, held together by hatred and love. ‘Opposition unites,’ say those of more elevated tone [Heraclitus], while the gentler ones [Empedocles] soften the tension of this perpetual condition and assert that the whole is at times unified and harmonious through the work of Aphrodite, and at other times multiple and at war with itself due to discord. (Sophist, 242 d–243 a)

Thus, Plato, following Hippias, weaves bold homological connections between philosophers and poets, a strategy he also employs in the Protagoras and Theaetetus to suggest that Heraclitus’ paradoxical discourse resonates not only with the Sophists but, through the complicity of Orpheus and Hesiod, even with Homer – despite Heraclitus’ explicit opposition to him.

Aristotle, too, in the Metaphysics, evokes the lineage of theological poets, notably Hesiod, though he remains focused on a specific thematic confrontation: the identity and distinction between principles governing corruptible and incorruptible things.

Those like Hesiod and all the theologians concerned themselves only with saying what seemed plausible to them, caring little for us. They asserted that the rulers were gods and that they were descended from gods, and they claimed that those who did not partake of nectar and ambrosia became mortal. Clearly, they knew what these names meant; yet the action of these causes they described in a way that is beyond our grasp. (Metaphysica III, 1000a 9–15)

The issue thus concerns the lost semantic transparency of entities like ‘nectar’ and ‘ambrosia’ – terms to which poetic tradition assigned names, but whose functions are no longer comprehensible, now buried in metaphor. This, according to Aristotle, is the inheritance of the poetic mode of speech, which tends toward personification:

The ancient poets approached the idea that the good develops as nature advances, insofar as they declared that rule and order were not held by the first – such as Night, Chaos, or Oceanus – but by Zeus; although, they happened upon these views by ascribing mutability to those who govern. Others among them, who speak in a mixed style and not wholly in mythical terms – like Pherecydes and some others – identified the first principle with what is best. So too did the Magi and some later sages, like Empedocles and Anaxagoras, who posited, respectively, Love and Intellect as the principle. (Metaphysica XIV, 1091b 4–13)

We can thus infer that not all within the theological tradition conformed to poetic convention; some – like Pherecydes and the Magi – developed forms of reasoning that blended lógos and mýthos, akin to that of the more advanced pre-Socratics.

Aristotle’s reconstruction of the differences among early thinkers – summarized in the first part of Table I – culminates in highlighting the closeness between Empedocles and the poetic-magical tradition. Plato had already hinted at this, but Aristotle now foregrounds it as an alternative doctrinal lineage.

Based on textual evidence, the proposed link between Hesiod, Parmenides, and Empedocles appears less implausible. Even in the diversity of their poems – whether theogonic, cosmogonic, or cosmological – certain recurring motifs and deep continuities emerge. Although the teeming pantheon described by Hesiod’s Muse, with its genealogy of gods, is absent from the other two works, Empedocles’ poem repeats the same convulsive dynamic of generation. In Hesiod’s narrative, the transition from Uranus to Cronus to Zeus illustrates the difficulty of power (dínamis) in establishing itself as a principle of order, being confused with the spontaneous force of generation. In Empedocles, generation likewise fails to produce natural order: its initial forms are disordered and chaotic. Parmenides, in contrast, treats any ordered coming-into-being as a problem of discourse entirely separate from that of being itself. Yet in all three texts, the acquisition of knowledge about this total vision of the cosmos and its generative-regulative principles presupposes a perspective that transcends human experience. This is achieved through a journey – a rapture beyond the physical limits of the world – made possible by the intervention of goddesses. Such a revelatory conversation with divinity is affirmed by both Hesiod (Theogony 32, 38) and Empedocles (DK 31 B 21, 9), who recount what was, is, and will be for mortals. Parmenides, however, fully immersed in the goddess’ revelatory discourse, adopts her ‘timelessness’: she reveals the totality of being, while rejecting the inadequacy of mortal language that denotes being through past and future tenses – when only the present would suffice.

Nonetheless, Empedocles, though making the opposite lexical choice (DK 31 B 16, 14, 31; B 8, 9), is equally aware of the gap between languages. He accepts the imprecision of mortal speech as a necessary tool to communicate what he has learned elsewhere, by other means – perhaps in another life.

And yet, across all these differing registers, Eros remains constant. Aristotle, Plato before him, and Plutarch centuries later (De facie in orbe lunae XII, 926d; DK 31 B 27) all note this. Curiously, Eros is the only deity that Hesiod describes solely in terms of function – as the cause of generative bonds, without itself being generative. In this role, it reappears unchanged in the works of both Empedocles and Parmenides, who grant less and less space to mythical personification.

Within Aristotle’s classification, it is Parmenides who appears to lose his identity – not because he cannot be placed, but because he could occupy more than one position. Aristotle mentions him alongside Hesiod, which might tempt us to align him with the poet-theologians; yet his thesis on the unity of being, introduced in Physics Book I, would just as rightly place him among the monists, in the first category on the left (see Box 1). If we follow instead what Aristotle writes in the Metaphysics, then the most appropriate placement for the leader of the Eleatics would be with Empedocles, among those who advocate a duality of causes of being. This ambiguity must be resolved by considering Aristotle’s conviction that Eleatic doctrine posed a serious obstacle to any inquiry into Nature. Hence, Parmenides and his followers are addressed at the very outset of the Physics: “Although they do not concern Nature, they happen to raise difficulties of a physical order, so it is good to speak of them equally, even if briefly” (Physica I, 185a 17-20). The paralyzing theses concerning the absolute immobility of being, typically attributed to Parmenides, are ascribed by Aristotle instead to Melissus of Samos and to Zeno’s dialectical prowess.

Parmenides himself is implicated only for the errors to which he led his less discerning followers; unlike them, Aristotle suggests, he proposed an escape route: “Compelled to attend to the phenomena, and believing – by reason – that the One exists, but – by sensation – that the many exist, Parmenides returns to positing two causes and two principles, heat and cold, likened to fire and earth. He then assigns heat to the side of being, and cold to that of non-being.” (Metaphysica I, 986b 31–987a 2) Thus, in a surprising turn, Aristotle reduces Parmenides to the status of a naturalist – perhaps even a pluralist.

This reading stands in open contrast with Parmenides’ own fragments, particularly given Aristotle’s attribution of non-being to one of the two principles. Yet the contradiction can be reconciled. Reconstructing Aristotle’s account, we find that he credits Parmenides with the most radical rejection of non-being, grounded in a rigorous linguistic absolutism; yet, he praises him for showing greater wisdom than his followers by reintroducing the sensory world through a dualistic schema – one of which, paradoxically, involves non-being. It is striking that Aristotle, usually so critical of Eleatic thought, refrains here from accusing Parmenides of blatant self-contradiction. What restrains him is likely the awareness that this is not a contradiction internal to Parmenides’ thought, but rather a product of Aristotle’s own interpretive superimposition. As with Thales, Aristotle extracts what is useful for philosophical debate, projecting his own terminology onto the text. The ‘non-being’ he refers to in interpreting Parmenides is not absolute non-being, but a technically defined absence relevant to his analysis of change and becoming.

Plato, too, presents a particular version of Parmenides: the philosopher of strict conceptual doctrine, champion of the immobility of being – an image aligned with how his students perceived him. Yet this image clashes with the poetic fervor with which Parmenides narrates his divine abduction and his encounter with the goddess who reveals the truth to him, as preserved in Simplicius’ commentary on the Physics, another key source on the pre-Socratics. The goddess brings him to a crossroads, from which one path leads to the contemplation of being, of which nothing can be said but: “It is now, all together, one, continuous. For what origin would you seek for it? How and whence its arising? Of non-being I will not allow you either to say or to think. For you can neither say nor think what is not.” (DK 28 B 8, 9-13)

Parmenides becomes the recipient of a blinding philosophical truth, which concerns not only the nature of totality, but also the proper way to know and speak about it. From the language of being – that is, the language of truth – are erased all negations that no longer apply to substance, space, or time: thus, differences, transformations, motion and displacement, generation and corruption, temporal markers, and all manifestations of multiplicity are excluded. These belong instead to the brotõn dóxai – the opinions of mortals.

With Parmenides, we reach the end of the Milesian quest for a principle (arché) conceived temporally as the primordial element from which all beings arise. There is no generation, for there is no time in which being could not be; there are no entities, because the whole is continuous; there is no beginning, because the whole is; nor can it be said that the whole has existed from all time, since that would imply the passage of time. “Remaining identical in the same state, it abides in itself, and so it remains immobile; for Necessity holds it fast in the bonds of a limit that encircles it on all sides – it is necessary that being be not incomplete.” (DK 28 B 8, 33–36)

Nothing can be affirmed by the philosopher except through the contemplation of the perfection of totality, which has a form: “Since there is an ultimate limit, it is complete on all sides, like the bulk of a well-rounded sphere, equally balanced from the center in all directions.” (DK 28 B 8, 46–48) The full sphere of being corresponds to the most categorical affirmation of its necessity.

Yet there is also the other path – the one that mortals followed when they began to speak of being as not-being (DK 28 B 8, 57–58). This is a fact that even the goddess cannot deny or prevent. If, on the first path, we encounter Plato dialoguing with Parmenides, on the second we find Aristotle, intent on shaping his own interpretation of Parmenides. Humans, marked by their use of differentiating names, speak of ethereal fire on one hand and lightless night on the other: thus, a cosmic ordering (diákosmon) accessible to the human mind comes into being (DK 28 B 8, 64). The goddess prepares to reveal this to her disciple Parmenides in a brief but notable outline of spherical astronomy, in which the Sun, stars, and Moon define their orbits around the Earth (DK 28 B 10, 5–7) – knowledge belonging to mortals, which Aristotle attempts to systematize. Yet even here, he omits certain crucial indications. In the language of mortals, names are used to designate things believed to be distinct – for instance, calling one thing darkness and another light – as if a real boundary could separate them. However: “Everything is full together of light and invisible darkness, equal to one another, for neither is there anything with the one nor with the other.” (DK 28 B 9, 3–4)

The language of mortals must therefore be employed with full awareness of its relativity: its distinctions do not capture the true nature of things. The world seen in its totality – viewed cosmologically, from the standpoint that, on the goddess’s advice, man adopts to reconcile the perception of multiplicity with the unity of truth – appears as a mixture of light and shadow. The distinction is illusory: in the uninterrupted motion of the Sun and Moon, there is now light, now darkness, with no perceptible boundary or difference. The sphere, offering no tangible limits, favors instead a seamless blending of one into the other. Perceptual differences experienced by humans beneath the vault of heaven are valid only within the limited horizon of the observer. This implies that the discourse on the truth of being does not belong to the philosopher as such, nor is it humanly graspable: Parmenides receives a revealed truth.

This element might lead us to see Parmenides not only as heir to Hesiod, but also as someone with literary roots: the structure of his poem reflects the tradition of the proem in the aoidic epic, of which the Homeric example is most familiar. While the poem introduces a grammatical innovation – the substantive use of the infinitive (e.g., ‘thinking,’ ‘being’) – which enables the abstraction of language, it also preserves Homeric diction, including vivid and even visceral metaphors. The term brotoí, for instance, used for mortals, derives from brótos, meaning ‘blood.’ A bifurcation similar to that faced by Parmenides appears in the Odyssey, in the episode recounting the fate of Oedipus (Odyssey XI, 271–280), where the relative knowledge of humans is contrasted with the absolute knowledge of the gods. On one side is human understanding: laborious, fragmentary, incomplete, and stretched over time. On the other is the totality of phenomena viewed outside the human framework, beyond time – a perspective accessible only to the gods and, by their grace, to exceptional individuals such as the aoidoi (bards).

Do we betray Parmenides by excluding him from this tradition and instead designating him a philosopher, as Plato desired, or a physicist, following Aristotle? It is, in fact, the followers of the Eleatic master who demand a figure embodying a rigorously defined dogma – one to be either followed or refuted in debate. For Aristotle, this uncompromising faction poses a threat:

Some actually believed that (p) what exists is necessarily one and immobile; and that there is no void. But motion is not possible without a distinct void; (q) nor is multiplicity possible without something to divide things. And there is no difference, according to them, between saying that the whole is not continuous but composed of contiguous bodies, and saying that there is multiplicity, not unity and void. For if the whole is entirely divisible, then there is no unity and, therefore, no multiplicity, but the totality is empty. By contrast, asserting that divisibility stops at a certain point is a fiction; for (r) up to what limit is it divisible, and why does one part behave in this way – remaining full – while the other is divisible? Moreover, (s) in any case, movement must be denied. On the basis of these reasonings they (t), surpassing sensation and scorning it, as if it were necessary to adhere only to reason, declare that the whole is one and immobile. (De generatione et corruptione I, 325a 2–15)

The positions attributed to Melissus (p) can be distinguished from those of Zeno (q, r), while the final assertions (s, t) are shared by the entire Eleatic school. According to Aristotle, the impenetrability of the Italic school lies not only in its disdainful rejection of other doctrines – reflecting the climate of open rivalry with Heraclitus – but also in its total indifference toward empirical observation. This renders it alien to the context of scientific discussion and links it instead to the past, to a cultural tradition rooted in that exclusive relationship with Truth which characterized the practice of the aoidoi (bards). “These men spoke thus, and for these reasons they seemed to speak of Truth. But from the standpoint of reason, these things may seem to occur; when one considers the facts, however, it seems almost madness to give credence to them.” (De generatione et corruptione I, 325a 16–19)

Among such ‘madness’ are the paradoxes produced by Zeno, who, by exploiting the infinite divisibility of time and space, argued that an arrow could never reach its target or that Achilles could never overtake the tortoise. The goal, here, is to deny the existence of motion and, consequently, the validity of any theory devised to explain how motion occurs. Despite his characteristic irony, Aristotle does not take these arguments lightly. He consistently regarded Zeno’s dialectical techniques with respect. Indeed, in Book IV of the Physics, Aristotle devotes significant attention to refuting the Zenonian paradoxes, and across the rest of the work he elaborates a theory of time aimed at preserving the intelligibility of the world of phenomena, governed by becoming and change.

The case of the Pythagoreans presents a distinct problem due to what Aristotle describes as a departure from naturalistic inquiry. Unlike the Milesian physiológoi, “they do not derive principles and elements from sensible things, since mathematical entities are motionless – except in the case of those involved in astronomy [...] They articulate causes and principles that are adequate to reach even the highest beings, and are more suited to these than to reasoning about Nature.” (Metaphysica I, 989b 31–990a 7) For Aristotle, the reason for this deviation from the naturalistic path lies in the incompatibility of mathematics with everything subject to generation and corruption. Mathematical principles are not derived from observing the transformation of sensible things, nor can they account for motion.

According to Aristotle, the Pythagorean project began with a bold analogy: numbers stood in relation to mathematical principles as mathematical principles stood in relation to all beings. If one then added that the even and the odd were the principles of all numbers, the conclusion followed that “the elements of numbers were the elements of all beings.” (ibid. 986a 1–2) Once a continuum was envisioned linking principles, elements, and the table of opposites, the physical world ceased to be investigated for its own sake and became merely a reflection of the mathematical world. The result was that the reigning numerical harmonies were taken as governing principles of the cosmos. Where such correspondences failed, “they hastened to bridge the gaps with additions, in order to render their treatment consistent.” (ibid. 986a 6)

To preserve the alignment between mathematics and reality, the Pythagoreans strove to conform the latter to the former. For example, “since it seemed that the number ten is perfect and encompasses the whole nature of numbers, they claimed that ten celestial bodies move in the heavens. And since only nine are visible, they invented a tenth – the anti-Earth.” (ibid. 986a 6–11) The arbitrariness of the anti-Earth hypothesis – introduced solely for theoretical symmetry – is the principal issue addressed in Chapter 13 of De caelo Book II. Yet that work also reveals more. Unlike Plato in the Republic, who in recounting the myth of Er invoked the Pythagorean musical analogy with the octahedron – relating the eight strings of the lyre to the distances between the nine celestial bodies – Aristotle turns his attention to what he sees as the most problematic core of Pythagorean astronomy: their rejection of geocentrism.

For they claim that fire is located at the center, and that the Earth is one of the stars and revolves in a circle around that center, thereby producing day and night. They also posit another Earth opposite this one, to which they give the name ‘anti-Earth’; for they seek reasons and causes not in relation to observable facts, but by forcibly subordinating phenomena to their own assumptions, attempting thereby to harmonize and integrate them into a coherent system. (De caelo II, 293a 21–27)

Despite the debate over what constitutes a legitimate object of observation, Aristotle does not fail to provide an accurate account of the theoretical alternatives – opposed, but equally valid – in explaining the alternation of day and night. Whether the heavens rotate around a motionless Earth or the Earth orbits a central fire, the observable effect is the same: “Nothing prevents, in their view, that even if we do not dwell at the center of the world, the phenomena might still appear just as they would if the Earth were at the center.” (De caelo II, 293b 26–29) From this comparison with the Metaphysics, another question arises: how could the Pythagoreans support both movements? It is likely that the motion of the heavens, in its entirety, was considered so slow as to be imperceptible or irrelevant to diurnal alternation, while being responsible instead for long-term astronomical phenomena – such as the precession of the equinoxes.

Aristotle, however, is not concerned with these subtleties. His aim is to highlight the theoretical prejudices that led the Pythagoreans to prefer a center of the cosmos inhabited by fire – identified, in their system, as the “watchpost of Zeus.” Yet this risks obscuring the reasons behind the anti-Earth hypothesis, reasons that Aristotle himself is well aware of: “They claim that [the Earth] moves in a circle around the center, and not only it, but also the anti-Earth [...] This is why lunar eclipses are more frequent than solar ones.” (ibid. II, 293b 19–24) Thus, as Aristotle tacitly admits, what appears to be an unfounded astronomical hypothesis stems in fact from observation: the greater frequency of lunar eclipses. This would suggest not only the existence of the anti-Earth, but possibly even other celestial bodies interposed between the Moon and the central fire.

In Aristotle’s reconstruction of Heraclitus’ thought, the philosopher’s use of oracular and religious language – rich in paradoxes, oxymorons, and apparent contradictions – does not appear to have particularly impressed him, except in brief but pointed references to Heraclitus’ rhetorical techniques and tactical use of contradiction (Rhetorica III, 1407b 11; Metaphysica IV, 1012a 25–1012b 32).

To understand Aristotle’s stance toward the Ephesian thinker, one must consider the clear opposition to the Eleatics that Plato attributed to Heraclitus:

But is not this very problem the one already passed down to us by the ancients, who, cloaking it in poetry to keep it from the common eye, declared that the origin of all things – Ocean and Tethys – were two ever-flowing rivers, and that nothing stands still? While the moderns, wiser than they, now state the same idea openly, so that even the cobblers might hear it and cease believing that some things rest while others move, realizing instead that all things are in motion – and thus they would rightly revere such philosophers. Unless I forget, O Theodorus, that others have proved the opposite, asserting, ‘Motionless, the universe has a name,’ and likewise all that Melissus and Parmenides argued, claiming that the whole is one and unmoving, since it has no space in which to move. (Theaetetus, 180d–e)

Aristotle seems to adopt Plato’s framing of Parmenides as isolated from subsequent developments:

To assert that all things are motionless, and to try to prove it by refuting sensation, is a kind of mental spasm. This view calls into question not merely one domain, but everything: not just the natural world, but all sciences and the opinions they depend on, since all rely on the assumption of motion. Just as, in mathematics, discussions of principles do not concern the mathematician per se, so, in other domains, what was just noted does not concern the natural philosopher. For Nature has been posited as a principle of motion. Even to say that everything is in motion may be false, but it is a lesser kind of falsehood – a methodological one: for in the study of physics, Nature has been defined as the principle of both motion and rest, and motion itself has been recognized as a property of Nature. (Physica VIII, 253a 32–253b 6)

Heraclitus’ doctrine, thus integrated into the lógos of Nature that Aristotle is constructing, no longer stands as a polar opposite to Parmenidean rationalism; rather, it helps temper its extremes. Beneath Heraclitean assertions lies an entire current of pre-Socratic thought which – starting even from Eleatic premises – recognized motion as an intrinsic manifestation of Nature, not its negation. Hence, there can be no science of Nature that does not begin with the study of natural motion. To affirm with Heraclitus that “all things are born or flow” is not to deny them a substratum, but to assert instead that there is “a single substance underlying them all.” (De caelo III, 298b 30)

While Heraclitus is only briefly mentioned among the cosmologists – primarily for his thesis on fire – he receives more attentive consideration when Aristotle’s inquiry into Nature becomes deeper and more technical. In Book I of De partibus animalium, Aristotle perhaps implicitly counters the Pythagorean tendency to restrict philosophy to the study of divine things by asserting that:

Even among beings that are not immediately appealing to the senses, Nature – through the structure it gives them – offers great joy to those who understand their causes; these are the true philosophers.” (De partibus animalium I, 645a 7–10) Shortly thereafter, Aristotle recounts an anecdote that captures Heraclitus’ philosophical posture: “Heraclitus, it is said, spoke to some foreigners who had come to visit him, but who, on entering and seeing him warming himself by a kitchen stove, hesitated. He invited them in without reserve, saying: ‘Even here, too, there are gods.’ Thus one must not be repelled by the investigation of any living being, since there is something natural and beautiful in each of them. (ibid., 645a 17–23)

Aristotle’s aim — as the case of Heraclitus illustrates — is not simply to reinterpret the doctrines of earlier thinkers for his own purposes, but also, drawing on the conceptual framework developed by Socrates and Plato, to reforge a link with the ancient tradition of naturalistic knowledge. His aim is to restore its logical foundations, argumentative coherence, and ontological correspondences, all of which had been undermined by the Parmenidean-Platonic crisis:

The reason our predecessors did not arrive at this mode of explanation is that they did not know the essence of the thing. Democritus was the first to touch upon the question – not because he deemed it necessary for natural science, but because the things themselves compelled him to do so. In Socrates’ time, this research progressed, but investigations into Nature were neglected, and philosophers turned their studies to practical virtue and politics. (De partibus animalium I, 642a24–31)

The case of Thales is exemplary: after stating his material arché, together with the corollary about the Earth’s buoyancy on water, Aristotle proceeds to find parallels in natural phenomena. He supplements the doctrine with his own considerations on the generative power of moisture, infers a probable causal law from it, and extrapolates broader concepts applicable elsewhere. These operations imply a level of abstraction – both in thought and language – that was unknown to the Milesians. Once retranslated and systematized in this manner, the doctrines of the early naturalists become plausible and, though partial, their results are to be both utilized and surpassed.

Aristotle’s intention is not to present himself as the final destination of this intellectual journey, but to indicate the direction in which further work should proceed, and to clarify the appropriate stance to adopt in relation to prior doctrines:

No theory about the world can assert itself in total independence from its predecessors; it must somehow encompass them, explaining what they had explained, if only by resolving what they could not. (Metaphysica II, 993a 31–b 11)

The competitive climate introduced by the Eleatics had already established that one’s position could only be justified after demonstrating the impossibility of alternative views. In this way, however, the entire field of phenomena – and the corresponding explanations offered by other theories – risked being irretrievably lost. This is why Aristotle holds that the natural science researcher must cultivate a form of historical consciousness, even if it is not organized according to the standards of historiography: it serves to relativize one’s own results by situating them within a shared context of inquiry. Such awareness enables a more comprehensive understanding of both the knowledge already developed and that which remains to be discovered.

Therefore, it is not only necessary to translate each assertion into terms that resonate with others, but also to work through the generalization of categories. Only under these conditions do comparisons become possible – comparisons that relate the partial results of individual thinkers to the overarching achievements of collective research. This brings us back to the use of the term arché, to which must now be added others such as kínēsis (motion), aitíai (causes), enantía (opposites), and hypokeímenon (substrate). These terms lead us toward a fuller definition of phýsis.

The significance of Aristotle’s unified discourse on the pre-Socratics becomes even clearer when it is read within another context – namely, that of his natural investigations – where the language, more precise when dealing with particulars, outlines the general issues more briskly, getting directly to the point:

The ancients, who were the first to philosophize about Nature, directed their inquiry to the material principle and cause of the same kind, asking what it was and how the Universe came to be from it, and what was the driving principle – for instance, hatred, or love, or intelligence, or spontaneity (toú automátou). The material substratum must necessarily possess a certain nature: for example, hot, as in fire; cold, as in earth; one light, the other heavy. Thus they conceived even the formation of the Cosmos. Similarly, they explained the formation of animals and plants. (De partibus animalium I, 640b 5-12)

In this context, the preliminary account of antecedents is condensed: one speaks of the substratum (hypokeímenon), which already functions as a material principle (hìlä); one refers to the moving principle and to the formation of the Cosmos. What is most significant, however, is the field-specific comparison of each individual thesis or notion. In this framework, each part of the animal can be identified and its function recognized by comparing it with descriptions provided by various pre-Socratic thinkers.

In such a climate, the positions of Thales and Anaximander are promptly interpreted in light of plausible physiological processes:

They say, for example, that because of the flow of water the stomach and every receptacle of waste are formed, or that due to the passage of inhaled air, the nostrils open.” (De partibus animalium I, 640b 12-15) These two elements, “are the matter of bodies, and from such bodies, all of them explain the constitution of Nature.” (ibid. 640b 16-17) That is, the action of a particular element in the functioning of the human body can be taken as a model for the behavior of all beings governed by natural principles. Yet in the human body, more than fire or earth, there are other elements that sustain life: “If man and animals are natural beings, as are their parts, then one must deal with flesh, bones, and blood. (ibid. 640b 17-19)

For Aristotle, it is necessary to move beyond the naive abstractions of the pre-Socratics to engage directly with the realities under investigation: “These statements are therefore overly simplistic, like a carpenter talking about a wooden hand. It is in this way that physiologists also describe the genesis and causes of bodily configurations: as if they had been manufactured by certain forces.” (ibid. 641a 5-9) This curious parallel leads directly to an argument dear to Aristotle: he momentarily adopts the image of the cosmic craftsman, a metaphor the pre-Socratics themselves employ when likening the Cosmos to an ordered artifact: “As a carpenter might speak of an axe or a drill, so they speak of air and earth; except that the carpenter would speak more accurately: for it would not suffice for him to say merely that as a result of a blow with his tool, now a cavity, now a flat surface appeared. He would also explain why he struck the blow and with what end in view; he would give the cause.” (ibid. 641a 9-13)

The cause in question is, of course, the final cause – that for the sake of which the individual parts of an animal exist in their completed form. The point Aristotle insists upon is the necessity of the final cause in explaining the existent. His invitation to the physiológoi is to embrace the analogy with artifacts: even in the case of a bed, it is easy to say that a design was used, but one must understand how that design came to determine each of the bed’s component parts. Thus, “it is necessary to state the proper determinations of the animal, describing what it is, which it is, and each of its parts.” (ibid. 641a 15-17) The statements of many cosmologists remain overly general, as if the search for causes concerned natural phenomena in the abstract: “The science of Nature cannot concern itself with any object derived from abstraction, since Nature does everything for the sake of an end.” (ibid. 641b 10-12)

Yet the end in question does not pertain to Nature as a whole, and it is a linguistic misstep to speak of a final cause in this sense. Indeed, télos suffers from the same overgeneralization that affects other terms such as arché. Only by analogy can one say that every existent form realizes a purpose. In both the Physics and the Metaphysics, Aristotle, though more elaborate in his discussion, is unequivocal: the unity of the final cause, even in Nature, is only analogical. This end is not one indicated by the order of all that exists, nor does it authorize the assertion of a unique final cause – an issue Aristotle is not immediately concerned with. Rather, appealing to an analogical unity means that each living being first actualizes its form for the sake of its own survival, and secondly ensures the continuation of its species, according to internal evolutionary rhythms that occur consistently in Nature. Therefore, “one should not harbor a childish distaste for the study of the lowliest living creatures: in all natural realities there is something marvelous [...] It is not by chance but by purpose that Nature’s works exist, and this is especially true: and the end for which they were constructed or formed belongs to the domain of the beautiful.” (ibid. 645a 15-26)

The beautiful mentioned here is that which arises from the wonder experienced upon discovering how each living thing fulfills its purpose – a contemplation that is gratifying in itself.

A distinct treatment is reserved for the three physiológoi – Anaxagoras, Empedocles, and Democritus – whom Aristotle consistently associates with one another, applying the same criteria seen elsewhere. They are discussed broadly in the Physics, De generatione et corruptione, and De caelo, and more specifically in the biological treatises De generatione animalium and De partibus animalium. It is here that the method of dialectical opposition proves most fruitful: through the interplay of pairings and contrasts, the thought of these three thinkers is examined in depth, and all possible lines of naturalistic investigation are explored.

In the Physics, Anaxagoras is assigned an intermediate position, while the unifying feature among the three is their shared theory of matter as composed of micro-constituents. Aristotle’s motivation for engaging directly with this debate is clearly stated in the Metaphysics: “Rather than resorting to Anaxagoras’ ‘all things together,’ or the mixture of Empedocles, or the formula of Democritus, it is better to say that they were all things together in potentiality, but not in actuality. Therefore, those philosophers had some notion of matter.” (Metaphysica XII, 1069b 19-20) These are complex theories of Nature. They no longer assume a static underlying substance with only superficial phenomenal variation; rather, they propose a radical distinction between macro-phenomena – constituting the reality we perceive – and micro-elements, which explain both their permanence and their transformations. In the comparison among these three authors, a fundamental difference emerges between what must be explained (the phenomenal world) and what explains it (the arrangement of elements), accounting both for the becoming of the manifold and the stability of the same. The real issue, in fact, is not simply the production of difference, but the persistence of identity across time: how can a species retain its form while generating ever-new individuals? The one/many dichotomy resurfaces within each species. Something must account for the potentially infinite generation of individuals, while something else must guarantee the preservation of form. This leads to a robust sense of causal theory – though, as we shall see, not quite as robust as Aristotle would prefer.

In the Physics, juxtaposing Anaxagoras and Empedocles reveals two distinct ways of resolving the one/many relation via the separation of opposites. For Anaxagoras, this separation occurs once and for all; for Empedocles, it happens rhythmically. Anaxagoras posits that fire, air, water, and earth derive from homeomeries, substances that retain their qualitative identity even when divided into parts. Empedocles, on the other hand, considers these same elements to be the simple bodies from which all other substances derive (Physica I, 187a 20; 188a 15). Yet both thinkers situate qualitative differences at the micro-level (De generatione et corruptione I, 314a 14; 314b 2; Metaphysica I, 984a 8-16). In contrast, when Anaxagoras is set against Democritus (Physica III, 203a 20-b 2), the key difference lies in whether elements are distinguished by quality or by quantity. Anaxagoras regards homeomers as qualitatively identical to the substances they compose; Democritus posits an undifferentiated substance, with differences arising only from size and spatial arrangement. What they share, however, is the assumption of an infinite number of elements, each capable of producing effects without limit – this in opposition to Empedocles.

Aristotle frequently revisits comparisons among these three physiológoi in order to draw out new and increasingly nuanced insights. For example: “If it is to be supposed that at one point nothing was in motion, then necessarily there are two options: either as Anaxagoras says, who held that everything was together and at rest from time immemorial until Mind introduced motion and separation; or as Empedocles maintains, that movement and rest return alternately in a cyclical pattern.” (Physica VIII, 250b 23-27) The key new element in this passage is motion: both pre-Socratics agree that it must be generated, but they differ on how. Anaxagoras sees motion as arising from a material infinity following temporal stasis; Empedocles envisions it as part of a rhythmic cycle. This already suggests that Democritus does not hold that motion is generated – we will find confirmation of this in the analysis of the atomist's theses.

Another subject of discussion highlighted in the Physics, through contrast among various thinkers, is that two of them – Anaxagoras and Democritus – postulate infinity (Physica III, 203a 20): “Anaxagoras speaks absurdly of immobile infinity. For he says that the infinite is firmly fixed in itself, because it is always within itself and nothing surrounds it.” (ibid. 205b 2–4) Aristotle later resumes his treatment of Anaxagoras from where he had left off: “He believes that, since all things were together and at rest from time immemorial, Intellect imposed motion and separation.” (ibid. VIII, 250b 24–26) The shadow of Anaximander looms large here, as he is invoked at the very moment the theme of infinity is introduced: “I deny that there is infinity as a principle, even though it seems to be so for all other things, as ‘encompassing and containing all.’ [...] And they say that this is divine – ‘immortal and ageless’ – as affirmed by Anaximander and most of the physiológoi.” (ibid. III, 203b 10–15)

In De caelo, Anaxagorean doctrines are introduced by contrast with those of Empedocles. According to Anaxagoras, the bodies we consider simple are in fact composites: “Air and fire are mixtures of these [the homeomers] and of all other ‘seeds’: each is in fact an aggregation of all the invisible homeomers. Therefore, everything is generated from these.” (De caelo III, 302b 1–4) Earth, water, and fire testify to their capacity for transformation, which means that they contain all the substances into which they might convert. In the aggregation, these components are not discernible due to their minuteness (the homeomers), but at the macroscopic level, it becomes evident that division into parts does not dissolve their qualitative identity. Air, likewise, is not an element and is not empty. On the contrary, it is full of all things; for this reason, it may be credited with the capacity to support the world: “Anaximenes, Anaxagoras, and Democritus claim that the cause of the Earth’s immobility is its flatness. It does not sever the air beneath it but lies atop it, just as we see flat objects do.” (ibid. II, 294b 14–16)

There is a suspicion that Aristotle is deliberately archaising the thought of the pre-Socratic, alternately associating him with Anaximander and then with Anaximenes. In truth, Aristotle seems to believe that Anaxagoras – while attempting to explain how the separation of homeomers from the undivided, unlimited whole occurs – approached the threshold of a theory of transcendent causality remarkably close to Aristotle’s own. Yet he failed to cross it, due to the primitive nature of his framework: “Anaxagoras uses Intellect as a kind of stopgap to account for the emergence of cosmic order. When he is unable to state the necessary cause of a phenomenon, he brings in Intellect; but in other cases, he attributes what happens to causes other than Intellect.” (Metaphysica I, 985a 18–21)

Better to take principles that are few and finite, as Empedocles does” (Physica I, 189a 15–16): with these words, the thought of the philosopher from Agrigento is introduced, though he notably lacks the transcendent cause suggested by Anaxagoras. The examination of the pre-Socratic takes place in two texts. The first is the Metaphysics, in which the affirmation of a principle as the cause of the destruction of all things – namely, Strife – would appear to be a firm and clear point. Yet it is precisely this principle which, according to Empedocles, generates all things by separation, with the sole exception of divinity. Aristotle quotes: “From it all things that were, are, and shall be came into being: trees and men and women, beasts and birds and fish nourished in water, and long-lived gods bloomed from it. (Metaphysica III, 1000a 29–32) He then resumes his critical assessment:

For if there had been no Strife among things, all would have remained one, as he says. For when all things were one, ‘Strife stood last’. But one consequence of Empedocles’ theory is that the most blessed god knows less than any other, because he knows nothing. Indeed, he does not possess Strife, and knowledge arises between like and like. [...] It was stated at the outset, and it is evident, that for him Strife ends up being the cause of destruction no less than of being; and likewise, Love is not a principle of being either, since by restoring everything to the One, it annihilates all other things. At the same time, Empedocles does not name the cause of this change, but simply says it happens by nature; and if the change is deemed necessary, he does not explain the cause of that necessity. (ibid. 1000b 9–17)

This critique targets the universal, cosmic role of the principles of Love and Strife, accusing Empedocles of inconsistency. Two principles are posited to account for the generation and dissolution of things: Love as the principle that holds elements together by blending their parts, and Strife as the principle of disintegration. But a reversal follows: coming into being – if a “whole together” is posited at the origin – can only result from Strife, which causes separation; Love, then, would be what resists the generation of distinct elements. Thus, each principle ends up playing two opposing roles.

“Empedocles employs these causes more than Anaxagoras, but still inadequately, and he does not use them consistently. For in his account, Love often divides and Strife unites: when the Whole is divided into the elements by Strife, fire and each of the other elements aggregate into unity; but when all the other elements converge toward unity through Love, the parts of each element are again separated.” (ibid. I, 985a 21–29)

Aristotle had already suggested that the confusion attributed to Empedocles’ system stems from terminological imprecision: the distinction between movement toward or away from the One is relative, since the One itself is not clearly defined, and thus the qualitative contrast between the two opposing motions is mischaracterized. That Empedocles wrote in verse gives Aristotle a pretext for intervening and reinterpreting his doctrine in his own terms: “Empedocles was therefore the first to introduce the principle of motion as divided into two causes, positing not one but opposing principles of motion, and he deserves credit for articulating the most accurate theory of matter, consisting of four elements.” (ibid. 985a 29–33)

With De generatione et corruptione, the focus shifts from cosmology to the core of the naturalistic problem. For Empedocles, it is difficult to explain generation according to nature: “All things that are naturally generated arise in the same way either always or for the most part, while those that occur outside this uniformity are due to chance or fortune. What then causes a man to come from a man, either always or most of the time, and wheat from wheat and not from an olive tree? Should we say that bone is generated when the elements are compounded in a certain way? Indeed, nothing is generated from a chance composition of the elements, as Empedocles himself acknowledges; some rational proportion is required.” (De generatione et corruptione II, 333b 4–11)

Again, Aristotle’s critical hammer falls, pointing out a paradoxical inconsistency: Empedocles speaks of natural elements and outlines a generative process based on their action, yet “he says nothing about Nature” (ibid. II, 333b 18). While there may be broad agreement on the theory of elements – except for Empedocles’ emphasis on the primacy of fire – he fails to identify the cause of constancy in nature. Aristotle, by contrast, attributes this to the stability of the proportions among the elements: “And when this is not due to proportion but to chance, the name applied is not proportion but chance; for it is possible for the mixture to occur fortuitously.” (ibid. 333b 15–16) In Aristotle’s view, it would be pointless to refer to elements or principles if their behavior were not governed by consistent criteria. Only under such conditions could Empedocles have properly articulated a concept of Nature: “What, then, is the cause of this [of natural events]? It is certainly not fire or earth; nor is it Love or Strife: the one causes union, the other division.” (ibid. 333b 11–13) Empedocles breaks his silence on the matter only to speak of “a mixing and changing of the things mixed” (ibid. 333b 14–15). The charge is one of excessive simplicity in his account of Nature; the inability to distinguish random or violent motions from natural ones – even at the level of elements – is taken as proof.

In the Physics, Aristotle observes that: “For Empedocles, air is not always placed highest, but only by chance. In his cosmogony he says, ‘Sometimes it rushes in this way, often otherwise,’ and he claims that the parts of animals are mostly generated by chance.” (Physica II, 196a 20–24) Yet for a similar claim regarding another element in De generatione et corruptione, Aristotle draws a more forceful conclusion: “Strife separated them, but ether was not driven upward by Strife; rather, sometimes he says it is driven by something like chance [...]; at other times he says it is the nature of fire to be carried upwards [...] And simultaneously, he also claims that the current cosmic order under the rule of Strife is the same as it was under the rule of Love.” (De generatione et corruptione II, 334a 2–8)

Aristotle’s negative judgment hinges on terminological imprecision, which, in his view, leads Empedocles to affirm chance instead of nature.

If the foundations of atomistic physics are at odds with Aristotle’s thinking, how can he then share its quality? “Leucippus and Democritus explained most methodically and gave the most universal explanation, since they took as a principle that which is so by nature” (ibid., 324b 35–325a 2). Aristotle’s praise, therefore, goes to the atomists for taking as the principle of Nature that which is inalienable from it. If one has fully understood the meaning of the appeal to Heraclitus, the cause is motion. One must, however, understand how Democritus and Leucippus somehow managed to reintroduce this phenomenon into the philosophical scene after the Eleatic crisis. In the pages of the Metaphysics, Aristotle shows how the operation was performed by conveniently maneuvering the very assertions of the Eleatic school: “Leucippus and his disciple Democritus hold that the elements are the Full and the Void – calling the one ‘what is’ and the other ‘what is not.’” (Metaphysica I, 985b 4–6) Interesting at this point is the connotation of non-being, i.e., emptiness: “They say that being is nothing more than non-being because neither is the body anything more than emptiness.” (ibid., 985b 8–9)

The reasoning carried out in De Generatione et corruptione runs in a parallel fashion, starting from the assumption of the Eleatics that “from what is truly one cannot generate a multiplicity, nor, from what is truly multiple, a one” (ibid., I, 325a 34–36). Leucippus and Democritus believed that they possessed a solution by positing the existence of some elements “which, in accordance with sensation, destroyed neither generation, nor corruption, nor movement, nor multiplicity of things” (ibid., 325a 24–25).