The history of infinitesimal geometry, and especially the part dealing with areas and volumes, surfaces and curved solids, is characterized by a particular aspect. After reaching the heights we know from Archimedes’ writings, research came to an abrupt halt for more than a millennium, only to resume in the ninth century with the Arab mathematicians. Over the course of two centuries, thanks to the latter, it reached other peaks before stopping again – no less decisively than in the third century BCE. A new revival occurred in the seventeenth century, and this time the research did not stop again. This is a historical phenomenon that has not been sufficiently emphasized, but which deserves analysis in order to clarify the reasons why research experienced these two beginnings and these two interruptions.

However, an anomaly never comes alone. The impact of Archimedes’ writings in this field, starting in the ninth century, appears under a somewhat paradoxical light. Very little of these writings was known in Arabic – just two treatises in all: On the Measurement of the Circle and On the Sphere and Cylinder. Yet, despite the small number of translated texts, a multiple and high-level research rapidly began. Due to how the Archimedean Corpus was preserved and transmitted, only a modest number of Archimedes’ works were known in Late Antiquity. In the sixth century, Eutocius seems to have known only the two cited above, and the situation in Arabic science was identical. All evidence indicates that the translators did not have the full Archimedean Corpus at their disposal, unlike the works of Euclid or Apollonius. We can even assert without fear of contradiction that Arab mathematicians knew only the two aforementioned treatises from Archimedes on infinitesimal mathematics. This conclusion is drawn from the examination of their works, and confirmed by the twelfth-century mathematician Ibn al-Sarīʾ. They were not aware of On the Quadrature of the Parabola, Conoids and Spheroids, The Spiral Lines, The Method, neither directly nor indirectly. This fact is important because the Archimedean method of integral sums that complemented the method of exhaustion is applied only in Conoids and Spheroids and The Spiral Lines – treatises that Arab mathematicians did not know. Nor were Archimedes’ methods for determining the area of a parabolic sector or the volume of a paraboloid sector known to them.

The question thus reduces to discovering how these two treatises were received in the Arabic tradition – and this will be important in identifying the aspects that characterise the Arab mathematicians belonging to the Archimedean tradition. Meanwhile, those who received and studied them were engaged in research on conic sections; some time later, at least from the Banū Mūsā onwards, they had Apollonius’ Conics at their disposal. These mathematicians were also interested in disciplines that today might be called ‘applied’: astronomy, statics, mechanics and optics. From this interest emerged the development of research on the conics: their optical properties; plotting point by point through geometric transformation; continuous plotting by specially constructed instruments; and research on projective methods. We therefore expect from them the introduction of other methods in addition to those of Archimedes, or the strengthening of techniques used by him but in a fragmentary way. Indeed, these mathematicians, engaged in the study of point transformations and projections, would combine such methods with infinitesimal techniques. They were also aware of the work of their algebraist colleagues, which in some way influenced their research in infinitesimal geometry. We are in the presence of a body of knowledge that would imprint on the concepts and methods of the Arabic authors of the Archimedean tradition and determine the development of research in infinitesimal geometry. We therefore expect to see them not only deepen the understanding of asymptotic behaviours and infinitesimal objects, but also extend the field of research to include sectors of infinitesimal geometry not explicitly treated by the Syracusan mathematician: isoperimetric problems in the plane and in space, solid angle, lunes. It becomes clear, therefore, that these Archimedeans are not, like Eutocius, commentators of Archimedes, but his emulators. Moreover, the number of commentaries and Arabic editions of the two Archimedean treatises on infinitesimal geometry is extremely limited: as far as we know, there are only those by al-Kindī on On the Measurement of the Circle, by al-Māhānī on On the Sphere and Cylinder, and by Nāṣir al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī on both treatises. Let us now briefly and systematically consider the various sectors of this infinitesimal geometry in the mathematics of the classical Islamic period.

The first known Arabic text on Archimedean problems is a commentary by the philosopher and mathematician al-Kindī on the third proposition (approximation of π) of On the Measurement of the Circle, entitled Risālat al-Kindī ilā Yūḥannā ibn Māsawayh fī taqrīb al-dawr min al-watar (Epistle of al-Kindī to Yūḥannā ibn Māsawayh on the Approximation of the Ratio of the Circumference to the Diameter), written before 856. Already in this work, the impact of algebra can be seen. Al-Kindī uses algebraic vocabulary for certain terms and to express ratios between numbers and segments – ratios that no ancient Greek would have admitted. This commentary would also become known in Latin, as suggested by the famous ‘Florence Versions.’ The true renewal of research on Archimedean problems begins with three contemporaries of al-Kindī, the brothers Muḥammad, Aḥmad, and al-Ḥasan, all known as the Banū Mūsā. They are the authors of the celebrated Kitāb Maʿrifat misāḥat al-ashkāl al-basīṭa wa-ʾl-kuriyya (Book on the Measurement of Plane and Spherical Figures), the first work by Arab Archimedeans. Let us focus on this book, which dates from the time of the reception of Archimedes’ work.

A simple glance suffices to understand that it is indeed a book that fits into the Archimedean tradition, yet without taking On the Sphere and Cylinder as a model. In fact, the authors do not follow Archimedes’ approach, even though some fundamental ideas remain the same. In this treatise of eighteen propositions, they address four topics: the measurement of the circle, that of the surface and volume of the sphere, Hero of Alexandria’s formula for the area of a triangle, and, finally, the issue of the two mean proportionals and the trisection of the angle. At the end of the treatise, the Banū Mūsā assess their contribution, writing: “Everything we have described in our book is our own work, except the knowledge of the circumference from the diameter, which is due to Archimedes, and the knowledge of the position of two magnitudes between two others so that [all four] follow the same ratio, which is due to Menelaus, as we mentioned before” (Rashed 1996a, p. 132).

This statement, usually overlooked, instead deserves reflection. Let us briefly return to the study of the Banū Mūsā to understand the meaning of their declaration and at the same time their precise position in the Archimedean tradition. They begin by demonstrating the following proposition: given a circle of circumference $p$ and a segment of length $l$, two cases are possible: if $l < p$, one can inscribe in the circle a polygon of $n$ sides with perimeter $p_n$ such that $l < p_n < p$; if $l > p$, one can circumscribe about the circle a polygon of $n$ sides with perimeter $q_n$ such that $p < q_n < l$. The demonstration of the two cases rests on the existence of a circle of given circumference $p$ and a regular polygon. The authors assume that such a circle exists; for the polygon they rely on Prop. 16 of Book XII of Euclid’s Elements: “Given two circles with the same center, inscribe in the larger circle an equilateral polygon, having an even number of sides, that does not touch the smaller circle.”

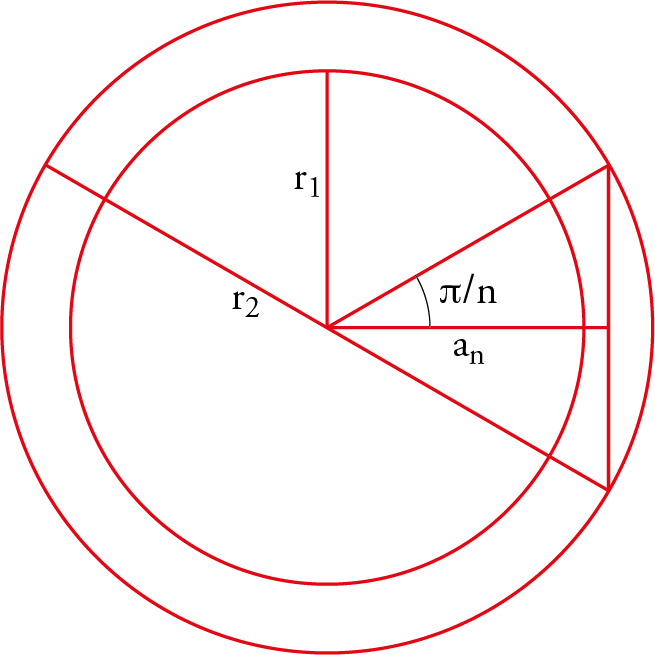

Note that for a regular $n$-gon to satisfy the problem, it is necessary and sufficient that its apothem $a_n$ meets the condition:

\begin{equation} r_1 < a_n < r_2 \Leftrightarrow r_1 < r_2 \cos \frac{\pi}{n} < r_2 \Leftrightarrow \frac{p_1}{p_2} < \cos \frac{\pi}{n} < 1\ \text{,} \end{equation}where $r_1$ and $r_2$ are the radii of the two concentric circles, $p_1$ and $p_2$ their respective circumferences (the existence of the integer $n$ depends on the continuity of the cosine function). However, contrary to what has been asserted, reference to the cited proposition from the Elements is not enough to establish the Banū Mūsā’s proposition; it must be completed by a homothety, a technique known to al-Ḥasan ibn Mūsā.

In the next proposition, the Banū Mūsā prove by contradiction the expression for the area of a circle as the product of the semidiameter by the semicircumference, i.e., $S = r p /2$. Note that to obtain a contradiction they do not compare $S$ with $S’ > S$, nor $S$ with $S’’ < S$, but only $p$ with $p’ > p$ and $p$ with $p’’ < p$, thus comparing lengths.

After thus determining the area of the circle, they turn to the approximation of π using Archimedes’ method, as they themselves affirm, but with some slight modifications. It is evident that the approach of the Banū Mūsā, as outlined above, differs from that of Archimedes in several respects. The first difference concerns precisely the application of the method of exhaustion and of its complementary technique, reductio ad absurdum. We have seen how, contrary to Archimedes, the Banū Mūsā bypass the most delicate point of the method of exhaustion – namely, the passage to the limit (to use our terminology) – by resorting to Prop. 16 of Book XII of the Elements, plus a homothety, a proposition whose demonstration is itself obtained precisely by passing to the limit. As for the reductio ad absurdum, we have seen that they compare lengths, not areas as Archimedes did. Finally, they do not determine the area of the circle by comparison with another figure, that of the right triangle in which one leg equals the radius and the other the circumference, but directly, as the product of two magnitudes. Under these conditions, one understands how their demonstration is shorter than that of Archimedes.

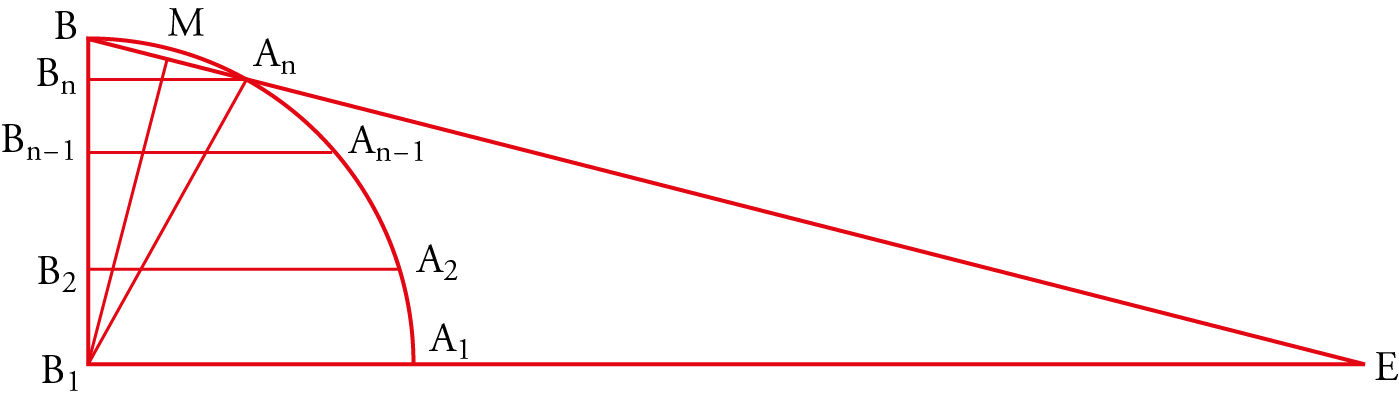

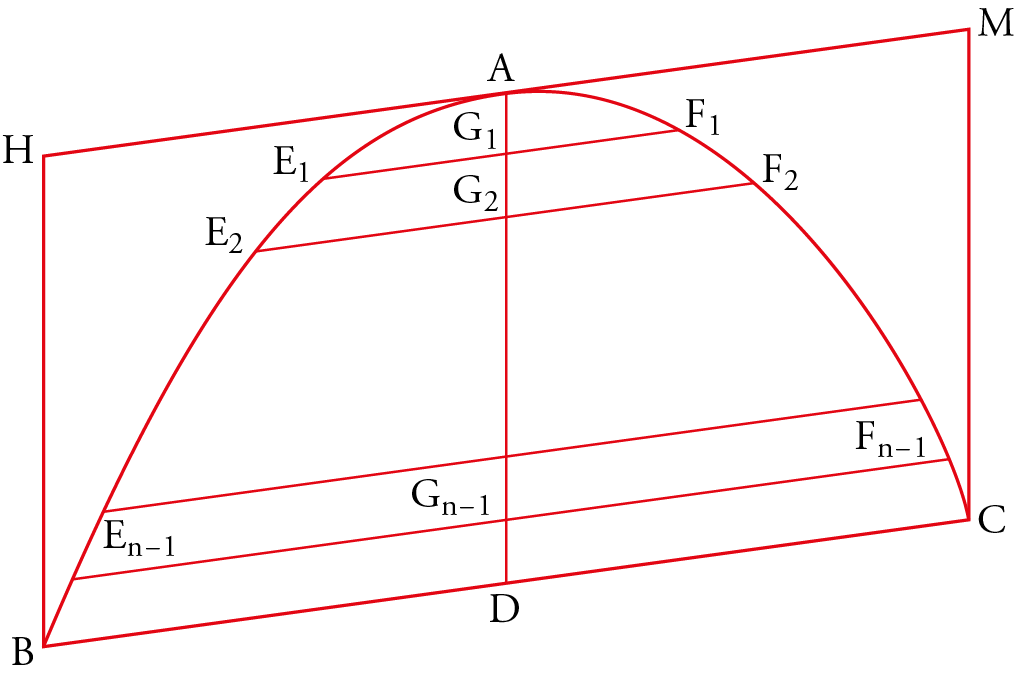

It remains to discover whether the path followed by the Banū Mūsā was chosen deliberately or was imposed by circumstances. To answer this, one must have an idea of the study they conducted on the second topic: the measurement of the surface area and the volume of the sphere. They begin by proving the following proposition (Prop. 11): the lateral surface area of a truncated cone of revolution with parallel bases is given by $S=l(p_1+p_2)/2$, where $l$ is the length of the slant height and $p_1, p_2$ are the perimeters of the two bases. Proposition 12 states that if one divides the quarter of a circle $A_1B$ into $n$ equal arcs by the points $A_2, A_3,\cdots, A_n$, then:

\begin{equation} A_1B_1 + 2\sum_{k=1}^n A_k B_k -B_1E \end{equation} \begin{equation} B_1 M^2< \frac{\ 1\ }{2}\ BA_n(B_1A_1 + 2\sum_{k=1}^n B_k A_k) < B_1B^2 \ \text{.} \end{equation}After computation, [2] and [3] become:

\begin{equation} 2\sum_{k=1}^n \sin k\cdot \frac{\pi}{2n} = \coth{\frac{\pi}{4n}}+1 \end{equation} \begin{equation} \cos^2{\frac{\pi}{4n}}<\cos{\frac{\pi}{4n}}<1 \end{equation}These relations are satisfied for every $n$.

In Proposition 13, they consider a semicircle in which a regular polygonal line with an even number of sides is inscribed. Within it, they draw the inscribed semicircle. By rotation, a hemisphere and a solid of revolution are generated, composed of a cone and various truncated cones, along with another hemisphere inscribed within the solid of revolution and sharing the same center as the first. The Banū Mūsā demonstrate that $2\pi R_1^2 < S < 2\pi R_2^2$, where $R_1$ and $R_2$ are the radii of the inscribed and circumscribed circles, respectively. We observe that the assumptions are those of Proposition 12, and that the demonstration uses Propositions 11 and 12, without employing Prop. 16 of Book XII of the Elements.

They are now able to apply reductio ad absurdum twice: first in Proposition 14 to obtain the lateral surface area of a hemisphere, which is twice that of a great circle, as they say, namely $S=2\pi R^2$; and second, to deduce the volume of the sphere as the product of the semidiameter by one third of the surface area, that is, $(4/3)\pi R^3$.

Here again we find the differences between Archimedes and the Banū Mūsā already noted in the case of the measurement of the circle. The first again concerns the method of exhaustion. This time too, the Banū Mūsā apply Prop. 16 of Book XII of the Elements, together with a homothety, and not Prop. 17 of the same book as has been believed. In fact, they consider a solid inscribed within the hemisphere composed of cones and truncated cones, whose surface lies outside that of a concentric hemisphere contained within the first. Such a solid is obtained from a regular polygonal line inscribed in a great circle of the sphere and not touching the great circle of the second sphere contained within the first (thus again starting from the cited Prop. 16 of Euclid). This procedure allows them to avoid the passage to the limit with the series of sines already mentioned. On the other hand, even here, when it comes to determining the volume of the sphere, the reductio ad absurdum is applied to the lateral surfaces and not to the volumes. Finally, the volume of the sphere is not given, as in Archimedes, in terms of another volume (a cone having as base a great circle of the sphere and as height the radius), but as the product of two magnitudes.

This study by the Banū Mūsā had important effects on mathematics, albeit of varying nature. First of all, in the Arab world, this initial phase – which would be quickly surpassed – had a certain impact on research, but above all on teaching. Beginning with their collaborator Thābit ibn Qurra, and for a century and a half, the study of the measurement of curved surfaces and volumes continued. This tradition rediscovered the method of integral sums, while developing geometric methods to facilitate the application of the method of exhaustion, such as affinity. The measurement of the sphere would later be revisited by Ibn al-Haytham, who used Darboux sums. In the Arabic tradition, the treatise of the Banū Mūsā would survive primarily as a teaching text, as demonstrated by the large number of copies found in manuscript collections, evidently intended for this purpose. In Latin, the situation is entirely different. Translated by Gerard of Cremona, the treatise, together with Archimedes’ On the Measurement of the Circle (translated into Latin from the Arabic version), became the main reference work in Archimedean mathematical research. Among many others, Fibonacci, Jordanus de Nemore, the anonymous author of the Liber de triangulis, and Roger Bacon showed interest in this treatise.

We have noted that modern commentators on this treatise, albeit in excellent works, have been misled in believing that the Banū Mūsā relied solely on Prop. 16 of Book XII of Euclid and especially in claiming that they used the subsequent Prop. 17. This oversight stems from the failure to recognize the explicit use of geometric transformations (homothety), since the contribution of the Banū Mūsā has been examined in light of the old geometry. One need only consult the book by al-Ḥasan ibn Mūsā on the ellipse, entitled Kitāb al-shakl al-mudawwar al-mustatīl (Book on the Elongated Circular Figure), to understand the growing importance in geometry of the study of geometric transformations. It is precisely in this direction that Arabic geometry would increasingly depart from its Greek and Hellenistic origins. This is a fundamental thesis for us, and it requires, among other things, rewriting the history of geometry in that era.

To highlight only what concerns us here, from the very beginning it is observed that the Archimedean tradition in Arabic, in developing an infinitesimal geometry, tends to orient geometric research toward the study of pointwise transformations. The history of this tradition thus appears in a new light, and the position of the Banū Mūsā is redefined. We now turn to this second book, which is, in our view, essential for understanding the first. Al-Ḥasan ibn Mūsā sets out to determine the area of the ellipse and of elliptical sections. We know that he did not yet have an intelligible version of Apollonius’s Conics. His research also aimed to develop the study of conic sections starting from the plane sections of the cylinder. It was only after his death that his brother Aḥmad ibn Mūsā found Eutocius’s edition of the first four books of the Conics, making possible the Arabic translation of the entire seven-book work of Apollonius (the eighth having already been lost in Greek).

In other words, al-Ḥasan ibn Mūsā sought to achieve two objectives: one, so to speak, Archimedean, concerning the measurement of an area bounded by a curve; the other, in the tradition of Apollonius (even if he could not fully know the Conics), concerning the study of the geometric properties of curves. He combines the notions of projection and orthogonal affinity with the application of Prop. 2 of Book XII of the Elements and reductio ad absurdum: it is the first change of direction in Archimedean mathematics.

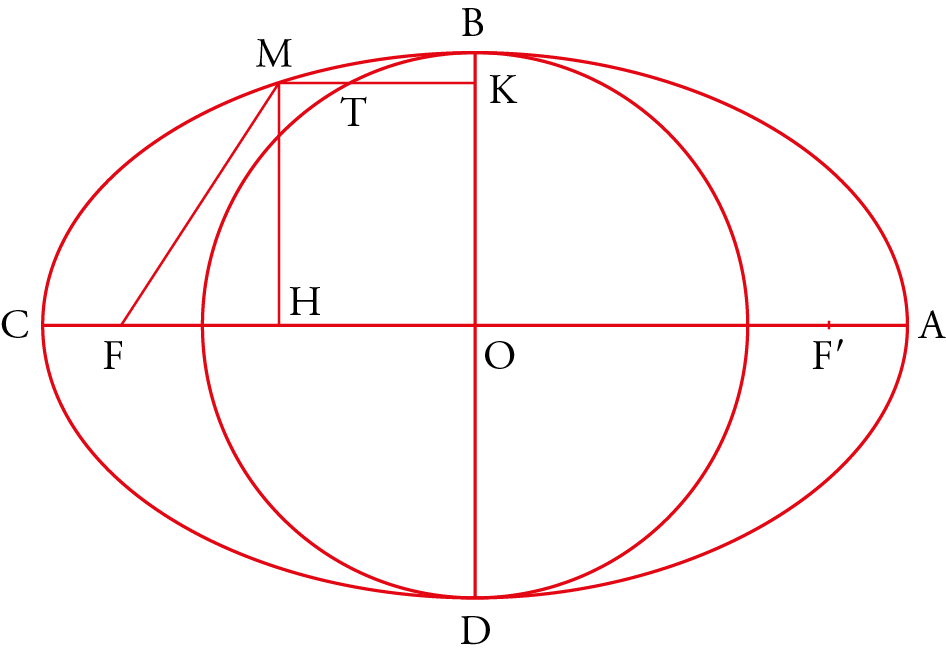

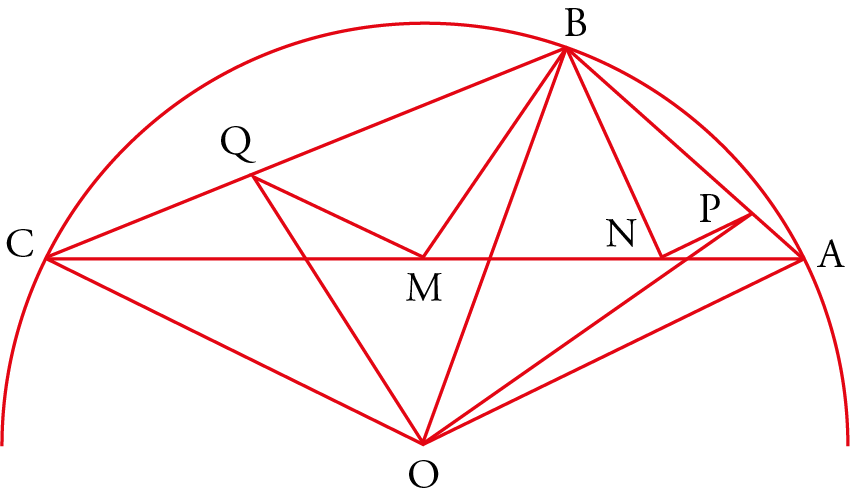

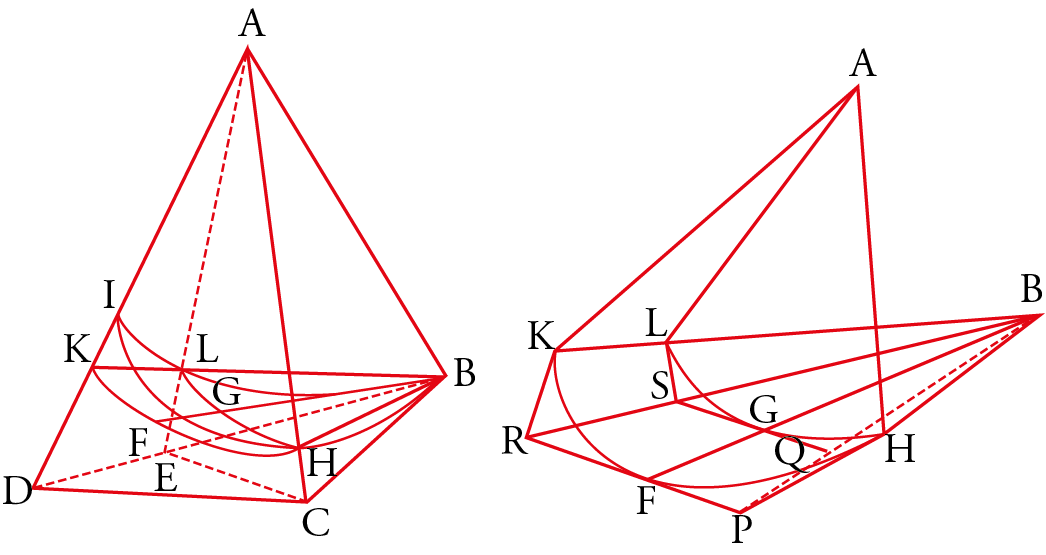

Following Ibn al-Samḥ’s book, which summarizes al-Ḥasan ibn Mūsā’s treatise, the latter’s procedure unfolds as follows: he begins with the “elongated circular figure” (fig. 4) defined by the bifocal property $MF+MF’=2a$, where $2a$ is the major axis, to then establish that the plane section of a cylinder of revolution by a non-base-parallel plane – i.e., an ellipse – shares the same properties as the first figure. He then determines the axis of the ellipse and finally studies the properties of chords, arrows, and so forth.

The outline of his deductive reasoning shows that the first six propositions concern the elongated circular figure – its vertices, center, diameters, chords, axis, the inscribed circle having the minor axis as diameter, and the circumscribed circle having the major axis as diameter. The next five propositions concern the ellipse as a plane section and its identification with the previous curve. Then follows a group of eight propositions dealing with the measurement of the area of the ellipse. Let us consider these groups in summary.

In the penultimate proposition of the first group (Prop. 5), one reads: if one associates to a point M of the elongated circular figure the point $T$ of the inscribed circle having the same ordinate ($MT$ is orthogonal to $BD$ at point $K$), it holds that: $MK^2=KT^2 + ¼(OA^2-MF^2)^2$ which, in the coordinate system $y=MK, y=MH$, with $AC=2a, BD=2b, F_1F_2=2c, KT=X$, and $MF=a-(cx/a)$ (relation previously established), can be rewritten as

\begin{equation} x^2-\frac{c^2}{a^2}\ x^2+y^2=b^2 \end{equation}(dividing by $b^2$ yields the equation of the ellipse). Prop. 6 concerns the orthogonal affinity relative to the minor axis:

\begin{equation} \frac{MK}{TK}=\frac{OA}{OB}\Leftrightarrow \left[\frac{x}{X}=\frac{a}{b}\right] \text{;} \end{equation}from this, and from the previous equation, one obtains:

\begin{equation} x^2\left(1 - \frac{c^2}{a^2} \right) = X^2 = b^2 - y^2 \Leftrightarrow b^2 x^2 = a^2 X^2 \text{,} \end{equation}which yields:

\begin{equation} \frac{x}{X}=\frac{a}{b}\ \text{,} \end{equation}an orthogonal affinity with axis $BD$, ratio $a/b>1$, in which the elongated circular figure $ABCD$ is the image of the circle of diameter $BD$ (this affinity is a dilation).

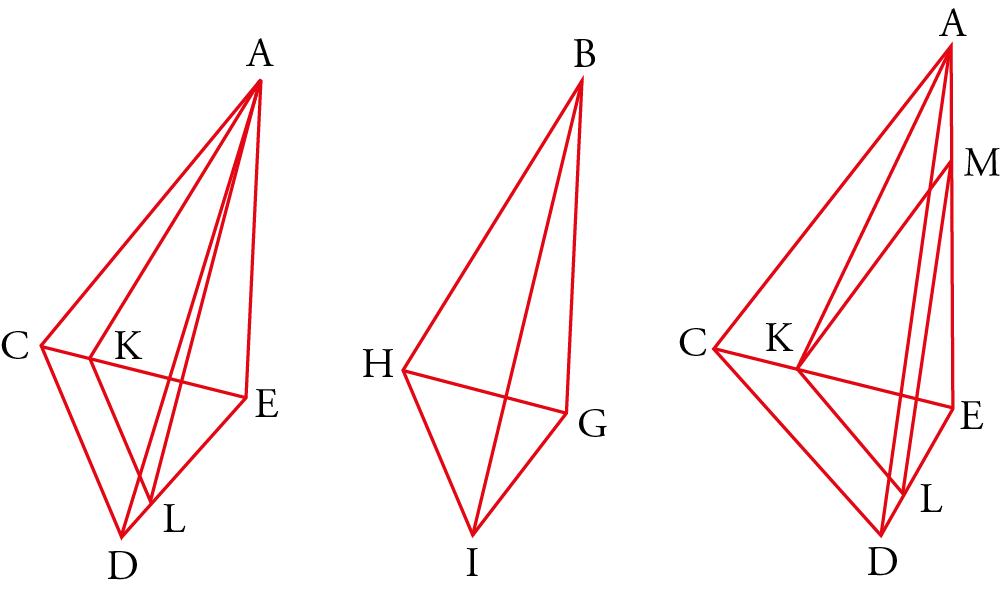

In the second group of propositions, devoted to the ellipse as a plane section of the right cylinder, al-Ḥasan ibn Mūsā, after recalling the property that the section of a right circular cylinder by a plane cutting the axis and not parallel to the base is an ellipse with center on the axis, considers a family of curves that deform continuously from the circle to the ellipse. He then studies the orthogonal affinity relative to the minor axis (Prop. 7): let an ellipse $ADBG$ and an inscribed circle $EDZG$ (fig. 5) be given; if a line parallel to $AB$ intersects $GD$ at $H$, the circle at $K$, and the ellipse at $T$, then:

\begin{equation} \frac{HT}{HK}=\frac{AB}{GD}=\frac{a}{b}\ \text{.} \end{equation}In the course of the demonstration, he considers the ellipse $ADBG$ as the flipped version of the ellipse $DLG$ obtained by rotating $ADBG$ around $DG$ on the plane perpendicular at $N$ to the axis of the cylinder. The circle $DEG$ is the cylindrical projection of the ellipse $DLG$ onto this same plane.

In Prop. 8 he studies the orthogonal affinity relative to the major axis. The ellipse is considered in this case as the image of the circumscribed circle in an orthogonal affinity of ratio $a/b$ (a contraction). In other terms, and in analytic language unknown to al-Ḥasan ibn Mūsā, if in an orthogonal reference the ellipse $ \mathscr{E}$ and the circles $ \mathscr{C}_1$ and $ \mathscr{C}_2$ are defined as follows $a>b$

\begin{align} \mathscr{E}=\left[(x,y)\ , \frac{x^2}{a^2}+\frac{y^2}{b^2}=1\right]\ ,\notag\\ \mathscr{C}_1=\left[(X,Y)\ , X^2+Y^2=b^2\right]\ ,\notag\\ \mathscr{C}_2=\left[(X,Y)\ , X^2+Y^2=a^2\right]\ \text{;} \end{align}and if $\psi$ and $\varphi$ denote the dilation and contraction already seen, then:

\begin{align} \mathscr{E}=\psi(\mathscr{C}_1)\ ,\quad\text{with}\ \psi\ :\ (X,Y)\rightarrow(x.y)\ :\begin{cases}x=\frac{a}{b}\ X\\y=Y\ ,\end{cases}\notag\\ \mathscr{E}=\varphi(\mathscr{C}_2)\ ,\quad\text{with}\ \varphi\ :\ (X,Y)\rightarrow(x.y)\ :\begin{cases}x=X\\ y=\frac{b}{a}\ Y\ . \end{cases} \end{align}At this point, he demonstrates that the two figures, the elongated circle and the ellipse, are superposable point by point (Prop. 9). These are the conceptual tools he then uses to determine the area of the ellipse. First, he shows by means of a dilation that the ratio between the area of a polygon inscribed in the ellipse and that of a polygon inscribed in the circle inscribed in the ellipse is equal to the ratio between the major and minor axes. He then specifies these results to obtain π ab as the area of the ellipse.

This, in brief, is the method of al-Ḥasan ibn Mūsā, a path that sheds light both on the earlier book of the Banū Mūsā and on the results of their Archimedean heirs. The use of a homothety in the book of the Banū Mūsā is entirely natural; the recourse to pointwise transformations by their successors, such as Thābit ibn Qurra, his grandson Ibrāhīm ibn Sinān, and many others, originates with the Banū Mūsā themselves. Their profile is thus transformed: no longer a pale reflection of Archimedes’ commentators, but rather mathematicians who, in order to inaugurate a new tradition, begin by revisiting the old one. Their heirs, mathematicians of genius, would soon go even further, thereby paradoxically veiling their importance and role. Historians of mathematics have addressed this by attributing to their successors – especially Thābit ibn Qurra – some of their inventions, conflating two aspects that are in fact quite distinct: that which was transmitted by Latin mathematics and that which is found in Arabic mathematics.

As we have seen, at the very moment when two texts by Archimedes were being translated, the mathematicians of the 9th century were seeking their own paths to achieve the same results, or others entirely new. This quest for new paths is not limited among the Banū Mūsā and their successors to Archimedean teaching, but also appears in their work in mechanics and astronomy. Indeed, the same tendency can be observed in other mathematical disciplines: arithmetic, number theory, algebra, trigonometry, projective methods, etc., and in other scientific fields such as optics with al-Kindī and statics with Thābit ibn Qurra. This new scientific spirit that took shape in the 9th century – within the tradition of Hellenistic science but with great freedom from it, the freedom to invent, to critique, and to draw from other sources, such as Indian sources – explains at least in part a phenomenon that continues to surprise: the massive, repeated, and ever faster translation of the ancient heritage.

The contemporaries and heirs of the Banū Mūsā would very actively continue research in this field. One of their collaborators, Thābit ibn Qurra (826-901), would make a substantial contribution. He would write three treatises: one devoted to the area of a parabolic segment, a second to the volume of a paraboloid of revolution, and the third to the sections and lateral area of the cylinder. These works would serve as new points of departure for other mathematicians, who aimed to reduce the number of lemmas and to improve the methods. The measurement of the parabola would be taken up again, for example, by al-Māhānī, by Ibrāhīm ibn Sinān, and by Ibn Sahl, while that of the paraboloid would be further developed by al-Qūhī and later by Ibn al-Haytham. All this demonstrates the foundational role played by the writings of Thābit ibn Qurra in this topic, as in many others.

In the first treatise, Kitāb fī misāḥat qiṭʿ al-maʿrūj alladhī yusammā al-mukāfiʾ (Book on the Measurement of the Segment of a Cone Called Parabola), in which he aims to determine the area of a parabolic segment, Thābit ibn Qurra – who was unaware of Archimedes’ study on the subject – proves twenty-one results. The first ones concern the sum of various arithmetic progressions; for example, he demonstrates that:

\begin{align} 2\sum_{k=1}^nk^2= \frac{\ 1\ }{2}\sum_{k=1}^n(2k-1)^2+n^2+\frac{n}{2}\ \text{;} \notag\\\sum_{k=1}^n(2k-1)^2=\frac{4n^3}{3}-\frac{n}{3}\ \text{;}\cdots \end{align}After eleven arithmetic lemmas, he states four lemmas concerning sequences of segments, which he uses to study bounding arguments. In Lemma 14 he proves that: if $a$ and $b$ are two segments with a known ratio $a/b$, then there exists a positive integer n such that the sequence $(u_k)_{1\le k\le n}$ of the first $n$ odd numbers starting from 1, and the sequence $(v_k)_{1\le k\le n}$ of the first $n$ even numbers starting from 2, satisfy the following relation:

\begin{equation} \frac{n}{v_n\cdot\displaystyle\sum_{k=1}^nu_k}<\frac{a}{b} \end{equation}With this result, he introduces an approximation which he uses in the next lemma to achieve the subdivision of segments. The lemma states: let $AB$ and $H$ be two segments, and let $a$ and $b$ be two segments with a given ratio $a/b$. For any $n$, one has: (a) there exists a partition $(A_k)_{0\le k\le n}$, $k = 0, 1, …, n$, with $A_0=A$, $A_n =B$, such that

\begin{equation} \frac{A_k\ A_{k+1}}{A_{k+1}\ A_{k+2}}=\frac{u_{k+1}}{u_{k+2}}\quad \text{for}\quad\ 0\le k\le n-2\ \text{,} \end{equation}where $(u_k)_{1\le k\le n}$ is the sequence of odd numbers starting from 1; (b) there exists a sequence of segments $(H_j)_{1\le j\le n}$, $j=1, 2, \cdots, n$, with $H_n=H$, such that

\begin{equation} \frac{H_j}{H_{j+1}}=\frac{v_j}{v_{j+1}}\quad \text{for}\quad\ 1\le j\le n-1\ \text{,} \end{equation}with $(v_j)_{1\le j\le n}$ the sequence of even numbers starting from 2. If $n$ satisfies the earlier relation (14), then:

\begin{equation} \frac{n\ A_0\ A_1\cdot \displaystyle\frac{H_1}{2}}{AB\cdot H}< \frac{a}{b} \ \text{.} \end{equation}The proof rests on the subdivision of a given segment into a sequence of segments proportional to a given sequence, and on the generalization of Lemma 14, which introduces the approximation of segment sequences and thus the generalization of the upper bound of a sequence of segment ratios.

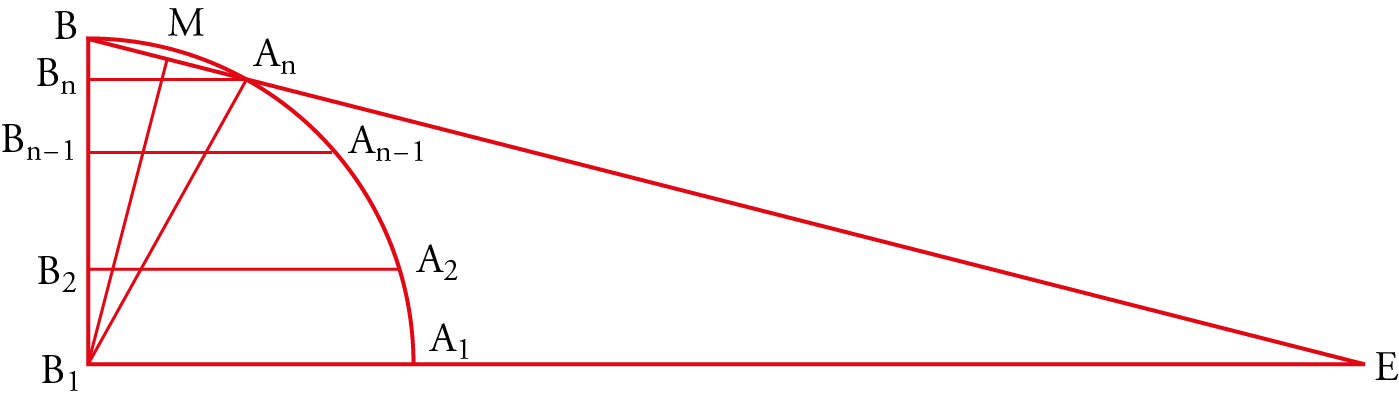

After the fifteen lemmas – eleven arithmetic and four related to sequences of segments – Thābit ibn Qurra tackles the calculation of the area of a parabolic segment. To this end, he proves four propositions. The examination of the lemmas and these propositions shows that he had a precise and rigorous understanding of the concept of the least upper bound (supremum) of a sequence of squares of real numbers and of its uniqueness. To characterize the supremum, he uses the following property.

Let $BAC$ be a parabolic segment with diameter $AD$, and let $S$ be the area of the parallelogram with base $BC$ associated with the parabola. Then, for every$\epsilon>0$, there exists a subdivision $A$, $G_1, G_2, \cdots, G_{n-1}, D$ of the diameter $AD$ such that the difference between the area of $BAC$ and the area of the polygon $BE_{n-1} \cdots E_2E_1AF_1F_2\cdots F_{n-1}C$ is less than $\epsilon$. He rigorously proves that the least upper bound of the areas of the polygons obtained is 2/3 of the area of $BHMC$, and he finally arrives at the following theorem: the area of the parabola is infinite, but the area of any segment is equal to 2/3 of the area of the parallelogram associated with the segment.

Let $\mathscr {S}$ be the area of the parabolic segment $\mathscr {P}$ and $\mathscr {S}$ the area of the associated parallelogram. If $(2/3)S \ne \mathscr {S}$, two cases arise. In the first case, $\mathscr {S}>(2/3)S$. Let $\epsilon >0$ such that

\begin{equation} \mathscr{S}-\frac{\ 2\ }{3}\ S=\epsilon \ \text{.} \end{equation}By Prop. 18, for this $\epsilon$ there exists $N$ such that, for $n>N$, the polygon $\mathscr {P}_n$ of the area $S_n$ satisfies:

\begin{equation} \mathscr{S}- S_n<\epsilon \ . \end{equation}From the above (18) and (19), $\lbrack (2/3)S+\epsilon\rbrack S_n$, so $(2/3)S < S_n $. But by Prop. 17, $(2/3) S > S_n$, which is a contradiction. In the second case, $\mathscr{S}< (2/3)S $. Let $\epsilon > 0$ such that

\begin{equation} \frac{\ 2\ }{3}\ S- \mathscr{S}=\epsilon \text{.} \end{equation}By Prop. 19, for this $\epsilon$ there exists $N$ such that, for $n>N$, the polygon $\mathscr {P}_n$ of area $S_n$ satisfies:

\begin{equation} \frac{\ 2\ }{3}\ S- S_n<\epsilon \ . \end{equation}Hence, by (20) and (21), \( [ \mathscr{S} + \epsilon ] - S_n < \epsilon \), or \( \mathscr{S} < S_n \). But \( \mathscr{P}_n \) is inscribed in \( \mathscr{P} \). This gives a contradiction. Hence, \( \frac{2}{3} S = \mathscr{S} \).

This theorem is equivalent to demonstrating the uniqueness of the least upper bound and essentially relies on the properties of the supremum. Indeed, we wish to demonstrate that $(2/3)S=\mathscr{S}$, knowing that:

\begin{equation} \mathscr{S}=\text{sup}(S_n)_{\scriptscriptstyle n\scriptscriptstyle\ge\scriptscriptstyle1} \end{equation} \begin{equation} \frac{\ 2\ }{3}\ S=\text{sup}(S_n)_{\scriptscriptstyle n\scriptscriptstyle\ge\scriptscriptstyle1} \end{equation}

By reductio ad absurdum, assume $\mathscr{S}\ne(2/3)S$. Two cases arise. In the first, if $\mathscr{S}> (2/3)S$, then there exists $\epsilon>0$ such that $\mathscr{S}= (2/3)S+\epsilon$. But since $\mathscr{S}$ is the least upper bound of the $S_n$, there exists an $S_n$ such that $S_n>\mathscr{S}-\epsilon$, so $(2/3)S < S_n$ – a contradiction, since $(2/3)S$ is also an upper bound of the $S_n$.

In the second case, if \( \mathscr{S} < \frac{2}{3} S \), then there exists \( \epsilon > 0 \) such that \( \frac{2}{3} S = \mathscr{S} + \epsilon \). But \( \frac{2}{3} S \) is the least upper bound of the \( S_n \), so there exists \( S_n \) such that \( S_n > \frac{2}{3} S - \epsilon \), hence \( \mathscr{S} < S_n \); absurd, since by (22) \( \mathscr{S} \) is an upper bound of the \( S_n \).

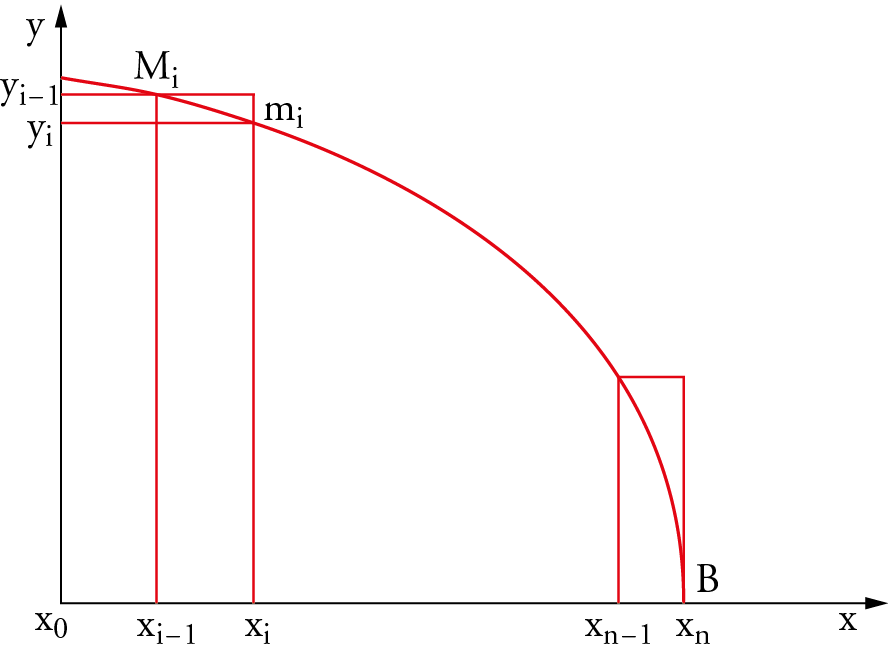

We do not claim that Thābit ibn Qurra, any more than his predecessors or successors until the 18th century, defined the concept of least upper bound. However, it does appear that he used the properties of the supremum as a guiding idea in the measurement of convex sets. In Ibn Qurra’s procedure one can in fact recognize the fundamental idea underlying the Riemann integral. Indeed, in the special case where the considered diameter is the axis of the parabola, the procedure is equivalent to considering a subdivision $\sigma = AG_1G_2\cdots G_{n-1}$ of the diameter $AD$, taking the sum

\begin{equation} S_{\sigma}=\sum_{i=1}^n(AG_i-AG_{i-1})\ \frac{G_{i-1}F_{i-1}+G_iF_i}{2} \end{equation}and proving that, for every $\epsilon >0$, there exists a subdivision s such that the difference between the area $ACD$ and $S_{\sigma}$ is less than $\epsilon$, and finally proving that $S_{\sigma}$ converges to this area.

Translating the above into the language of analysis: let $x_i$ be the abscissa of $G_i$ and let $y = f(x)$ be the equation of the parabola. $S_{\sigma}$ can then be written as:

\begin{equation} S_{\sigma}=\sum_{i=1}^n(x_i-x_{i-1})\ \frac{f(x_{i-1}f_{i-1}+f(x_i)}{2}\ ; \end{equation}but since

\begin{equation} f(x_{i-1})\le\ \frac{f(x_{i-1})+f(x_i)}{2}\ \le f(x_i)\ ; \end{equation}is a value assumed by $f$ at some point $x_i$ in the interval $[x_{i-1}, x_i]$, and since $f$ is continuous, it follows that

\begin{equation} \frac{f(x_{i-1})+f(x_i)}{2} \end{equation}is a value that $f$ takes at the point $\xi_i$ in the interval $x_{i-1}, x_i$. But $S_{\sigma}$ can then be written in the form

\begin{equation} S_{\sigma}=\sum_{i=1}^n(x_i-x_{i-1})\ f(\xi _i)\ ;\quad x_{i-1}\le \xi_i \le x_i \ \text{,} \end{equation}which is precisely the sum used in the definition of the Riemann integral of a function $f$. Lastly, observe that Ibn Qurra’s quadrature, given the definition of the parabola, is equivalent to calculating the integral $\int_0^a \sqrt{px}\, dx$. As the modern historian Adolf P. Youschkevitch wrote:

“Thanks to this procedure, Ibn Qurra revives the method of calculating integral sums, which had fallen into oblivion. Moreover, with this very method, Ibn Qurra effectively calculates for the first time an integral $\int_0^a x^n\, dx$ for a fractional exponent $n$, here $\int_0^a x^{1/2}\, dx$. In doing so, again for the first time, he subdivides the interval of integration into unequal parts. With a similar procedure, which consists in subdividing the x-axis into segments forming a geometric series, Pierre Fermat, in the mid-17th century, would address the quadrature of curves $y=x^{m/n}$ with $(m,\,n) \ne 1$.” (1976, p. 43)

After calculating the area of the parabola, Ṯābit ibn Qurra addresses the volume of a paraboloid of revolution in his Maqāla fī misāḥat al-mujassamāt al-mukāfiʾa (Treatise on the measurement of paraboloids). This involves a transition from plane geometry to solid geometry, and for this purpose he establishes thirty-six propositions divided into various groups. He ultimately demonstrates the following theorem: the volume v of a parabolic dome $ABC$ with axis $BD$ is half the volume $V$ of the cylinder with height $h$ and circular base with diameter $AC$:

\begin{equation} v= \frac{\ 1\ }{2}\ V=\frac{\ 1\ }{2}\ \pi h\ \frac{AC^2}{4}\ \text{.} \end{equation}The procedure is analogous to that used for determining the area of a parabolic sector. It involves dividing the diameter of a parabolic sector into segments proportional to the sequence of odd numbers. The points on the parabola corresponding to this division then have abscissas proportional to the squares of integers and ordinates proportional to the integers themselves. These points determine:

| in the plane | in space |

|---|---|

| 1. a polygon inscribed in the parabola and decomposed into trapezoids | 1. a solid of revolution inscribed in the paraboloid and decomposed into cone-like solids |

| 2. Let $s$, be the area of the parabola | 2. Let $v$, the volume of the paraboloid |

| 3. $S$, the area of the associated parallelogram | 3. $V$, the volume of the associated cylinder |

| 4. $s_i$, the area of a trapezoid | 4. $v_i$, the volume of a cone-like solid |

He shows that, given $\epsilon>0$, one can find an $N$ such that for all $n>N$, the following holds:

\begin{align} &\frac{2}{3}S-\sum_{i=1}^ns_i<\epsilon\ \text{(props. 17, 19)} && \frac{V}{2}-\sum_{i=1}^nv_i<\epsilon\ \text{(props. 32, 35)} \notag \\ &s-\sum_{i=1}^ns_i<\epsilon\ \text{(prop. 18)} && v- \sum_{i=1}^nv_i<\epsilon\ \text{(props. 33, 34)} \end{align}In other words, he demonstrates:

\begin{align} &\frac{2}{3}S=\text{sup}\sum_{i=1}^ns_i && \frac{V}{2}=\text{sup}\sum_{i=1}^nv_i \notag \\ &s=\text{sup}\sum_{i=1}^ns_i && v=\text{sup}\sum_{i=1}^nv_i \end{align}Through reductio ad absurdum, he proves the uniqueness of the supremum in both cases:

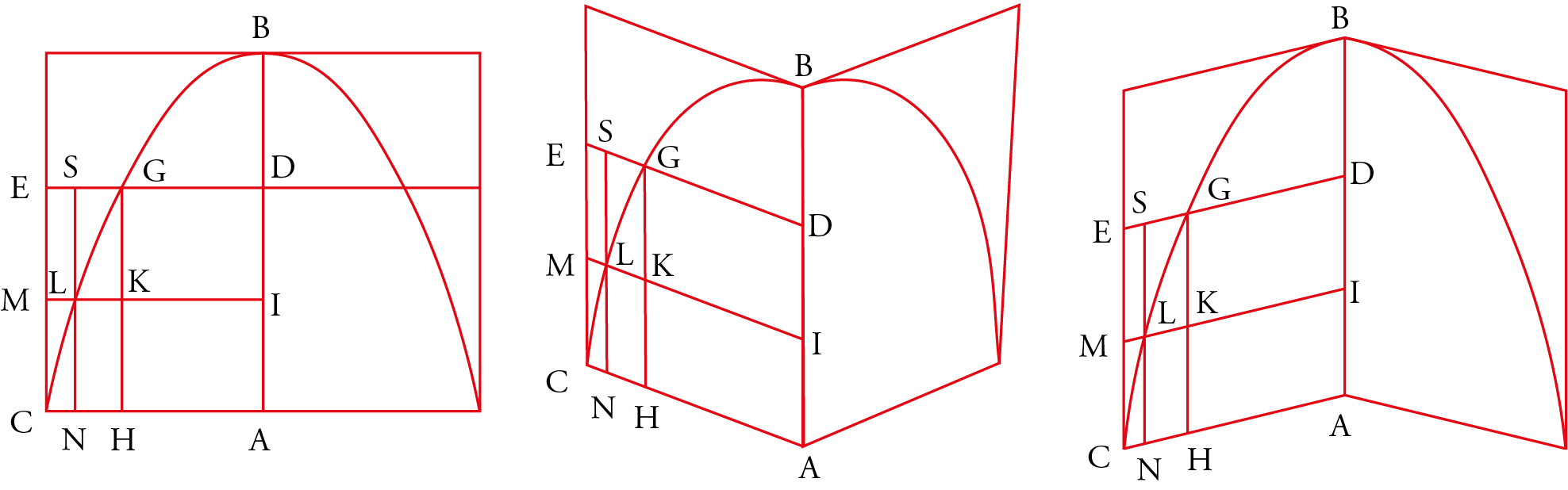

\begin{align} &s=\frac{2}{3}\ S\ \text{(prop. 20)}&& v=\frac{V}{2}\ \text{(prop. 36)} \end{align}Ṯābit ibn Qurra’s contributions in this field extend further. He composed a fundamental book, Kitāb fī quṭūʿ al-usṭuwāna wa-basīṭihā (Book on the sections of the cylinder and its lateral surface), in which he studies the various plane sections of a right and an oblique cylinder, determines the area of the ellipse and its sectors, discusses maximal and minimal cylinder sections and their axes, and finally determines the area of the lateral surface portion bounded by two plane sections. Like the previous two treatises, this one not only left a mark on the history of infinitesimal geometry, but is also one of the most important texts in all of geometry. Indeed, by addressing the study of geometric pointwise transformations, it directs geometric research in a new direction and in doing so fertilizes algebra. Traces of this influence are found in the works of, among others, Ibrāhīm ibn Sinān, Ibn Sahl, al-Qūhī, Ibn al-Haytham, and Sharaf al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī.

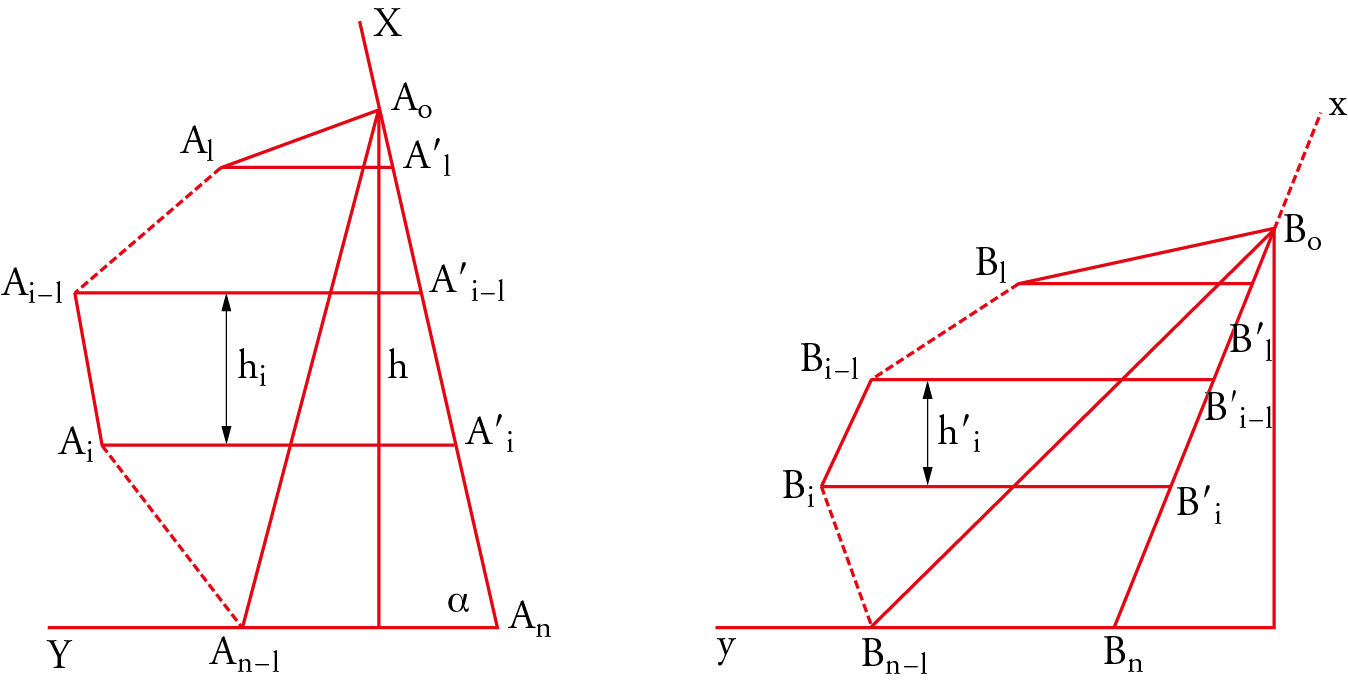

It is impossible to report here all the results and demonstrations of this rich and profound treatise. To fix ideas, let us mention just two propositions. In prop. 14, Ṯābit shows that if $S$ is the area of the ellipse $\mathscr{E}$ with semi-axes $a$ and $b$, and $\Sigma$ is the area of the circle $E$ with radius $r=\sqrt{ab}$, then $S=\Sigma$. The symbolic translation of his demonstration uses the following notation: $S$, area of the ellipse $\mathscr{E}$; $S_n$, area of $P_n$ inscribed in $\mathscr{E}$; $\Sigma$, area of the equivalent circle $E$; $\Sigma_n$, area of $\Pi_n$ inscribed in E; $S’$, area of the circumscribed circle $\mathscr{C}$; $S’_n$, area of $P’_n$ inscribed in $\mathscr{C}$. Suppose $S\ne\Sigma$. There are two cases. First, if $S>\Sigma$, then $S=\Sigma+\epsilon$. Let $P_n$ be a $2_{n+1}$-gon inscribed in $\mathscr{E}$, derived from $P_{n-1}$ by doubling its vertices through diametric cuts. $P_1$ is the rhombus defined by the ellipse’s vertices. If $S_n$ is the area of $P_n$, then successively:

\begin{align} &S_1>\frac{\ 1\ }{2}S\Rightarrow S-S_1< \frac{\ 1\ }{2} S \notag \\ &S_2-S_1>\frac{\ 1\ }{2} (S-S_1)\Rightarrow S-S_2<\frac{\ 1\ }{2^2} S \notag \\ &\cdots \notag \\ & S_n-S_{n-1}>\frac{\ 1\ }{2} (S-S_{n-1})\Rightarrow S-S_n< \frac{\ 1\ }{2^n}S \end{align}then, for $\epsilon$ given by $S=\Sigma+\epsilon$, there exists a positive integer $n$ such that $(1+2^n)S<\epsilon$, implying $S-S_n<\epsilon$ and $S_n>\Sigma$. Now consider the circle $\mathscr{C}$ and polygon $P’_n$ derived from $\mathscr{C}$ and $P_n$ via an orthogonal affinity with ratio $a/b$. Let $S’_n$ be the area of $P’_n$ and $S’$ the area of $\mathscr{C}$. We then have:

\begin{equation} \frac{S_n}{S'_n}=\frac{b}{a}=\frac{ab}{a^2}=\frac{\Sigma}{S'}\ \text{;} \end{equation}but since $S_n>\Sigma$ , it follows $S’_n>S’$, which is impossible. In the second case, if $S<\Sigma$ we similarly obtain a contradiction:

\begin{equation} \frac{\Sigma}{S'}=\frac{S}{S'-\epsilon'} \ \text{.} \end{equation}By taking again the circle $\mathscr{C}$ and the previous polygons $P’_n$, one obtains successively:

\begin{align} &S'-S'_1<\frac{\ 1\ }{2}\ S' \notag \\ &S'-S'_2<\frac{\ 1\ }{2^2}\ S' \notag \\ &\cdots \notag \\ &S'-S'_n<\frac{\ 1\ }{2^n}\ S'\ \text{;} \end{align}Then, for $\epsilon’$ defined as in (35), there exists a positive integer $n$ such that $(1/2^n)S’<\epsilon’$, hence:

\begin{equation} S'-S'_n<\epsilon' \ \text{.} \end{equation}If $P_n$ is the polygon inscribed in $\mathscr{E}$ corresponding to $P’_n$ under the orthogonal affinity of ratio $b/a$, then:

\begin{equation} \frac{S_n}{S'_n}=\frac{\Sigma}{S'}=\frac{S}{S'-\epsilon'}\ \text{.} \end{equation}But from (37), it follows that $S’_n>S’-\epsilon’$, which is absurd. After examining both cases, one therefore concludes $S=\Sigma$.

We pass from the ellipse $\mathscr{E}$ to the circle $\mathscr{C}$ with an orthogonal dilation $f$ of ratio $k_1 = a/b$, and from the circle $\mathscr{C}$ of radius $a$ to the circle $E$ of radius $r$ such that $r^2=ab$, with a homothety $h$ of ratio $k_2=r/a=\sqrt{ab}/a=\sqrt{b/a}$. Thus, $E=h\circ f(\mathscr{E})$; the transformation $h\circ f$ preserves area, since $K_1\cdot k^2_2 =1$. The aim of prop. 14 is precisely to demonstrate this property for the ellipse $\mathscr{E}$.

Using the previous notation, Thābit employs the equalities $\Sigma/S’=b/a=k^2_2$, and shows that $S_n/S’_n=b/a=1/k_1$ for every $n$, from which:

\begin{equation} S=\Sigma\Leftrightarrow\frac{S}{S'}=\frac{\Sigma}{S'}\Leftrightarrow\frac{S}{S'}=\frac{S_n}{S'_n}\ \text{.} \end{equation}His method consists of two steps. In the first, assuming $S_n / S’_n < S / S’$ , we get:

\begin{equation} \frac{S_n}{S'_n}=\frac{S-\epsilon_1}{S'}\ \text{.} \end{equation}One shows that there exists \( P_n \subset \mathscr{E} \) such that \( S^{\prime}-\epsilon_1 < S^{\prime}_n < S^{\prime} \); but \( f(P_n) = P^{\prime}_n \subset \mathscr{E} \) satisfies (40), from which \( S^{\prime}_n > S^{\prime} \), which is impossible.

In the second step, assuming $S_n/S’_n > S/S’$, we get:

\begin{equation} \frac{S_n}{S'_n}=\frac{S}{S'-\epsilon_2}\ \text{.} \end{equation}One shows that there exists \( P'_n \subset \mathscr{E} \) such that \( S^{\prime} - \epsilon_2 < S^{\prime}_n < S^{\prime} \); but \( f^{-1}(P'_n) = P_n \subset \mathscr{E} \) satisfies (41), from which \( S_n > S \), which is impossible. Thus, it is demonstrated that:

\begin{equation} \frac{S}{S'}=\frac{S_n}{S'_n}\ \text{.} \end{equation}

Hence, starting from the property of orthogonal affinity whereby the ratio of the areas$S’_n$ and $S_n$ of the two homologous polygons $P_n$ and $P’_n$ is equal to the affinity ratio $a/b$, for any $n$, Thābit deduces that the same holds for the area $S$ of the ellipse $\mathscr{E}$ and the area $S’$ of the circle $\mathscr{C}$. This amounts to saying that the ratio is preserved in the passage to the limit:

\begin{equation} \frac{S_n}{S'_n}=\frac{b}{a}\quad\text{and}\quad\frac{S}{S'}=\frac{\text{lim}\ S_n}{\text{lim}\ S'_n}=\text{lim}\ \frac{S_n}{S'_n}=\frac{b}{a}\ \text{.} \end{equation}Luca Valerio (1552-1618) will take such statements as the basis for his method (De centro gravitatis solidorum libri tres, Book II, props. I–III), a method which does not involve integral sums.

The same result is found in prop. 4 of Archimedes’ Conoids and Spheroids, a text that was unknown to the mathematicians of the time, including c. The comparison between Archimedes’ method and Thābit’s is doubly instructive: it enhances our appreciation of the ninth-century mathematician's contribution and helps us better understand the extent of knowledge about the Archimedean corpus in that era.

In Proposition 31, Thābit demonstrates that the lateral area $\Sigma$ of a portion of an oblique cylinder bounded between two right sections is $\Sigma=pl$, where $p$ is the length of a minimal ellipse and $l$ the length of the generating segment between the two sections. Let $\mathscr{E}$ be one of the sections, $K$ its center, and $2a$ the major axis. Let us distinguish again two cases.

In the first case, if \( \Sigma < pl \), there exists \( g \), with \( g < p \), such that \( \Sigma = gl \). Let \( h \) be such that \( g < h < p \); there exists an area \( \epsilon \) such that \( \Sigma + \epsilon = hl \), hence \( \epsilon = l(h - g) \). One constructs the ellipse \( \mathscr{E}_1 = \varphi(\mathscr{E}) \), where \( \varphi \) is the homothety centered at \( K \) with ratio \( a_1 / a \) such that \( 1 > a_1 / a > h / p \); by Proposition 26, the length \( p_1 \) satisfies \( p_1 / p = a_1 / a \), from which \( p_1 / p > h / p \), and thus \( p_1 > h \).

Let $P_n$ be a polygon inscribed in $\mathscr{E}$ and not touching $\mathscr{E}_1$, $P’_n$ its projection onto the other base, and $p_n$ the perimeter. If $\Sigma_n$ is the lateral area of the prism with bases $P_n$ and $P’_n$, then $\Sigma_n=p_n l$; but $p_n>p_1>h$, from which $\Sigma_n>hl$, and thus:

\begin{equation} \Sigma_n=\Sigma+\epsilon \ \text{.} \end{equation}a) If $\epsilon/2\ge s$, since the areas $s$ and $s′$ of the two bases—which are minimal ellipses—are equal, one has $\epsilon \ge s+s’$, from which $\Sigma_n>\Sigma+s+s’$. The lateral area of the prism inscribed in the cylinder would be greater than the total area, which is absurd.

b) If $\epsilon/2< s$, then a condition is imposed on $a_1$, namely $a_1^2/a^2>[s+(\epsilon/2)]/2$; but if $s_1$ is the area of $\mathscr{E}_1$, then $s_1/s=a_1^2/a^2$, from which $s-s_1<\epsilon/2$. If $s_n$ is the area of $P_n$ and $s’_n$ that of $P’_n$, one has $S_n=s’_n$, $s>s_n>s_1$, $s-s_n<\epsilon/2$ and $\epsilon>(s-s_n)+(s’-s’_n)$. From (44) one obtains $\Sigma_n>\Sigma+(s-s_n)+(s’-s’_n)$, which is absurd. From both (a) and (b) a contradiction is reached; therefore $\Sigma\ge pl$.

Let us now consider the second case: if $\Sigma>pl$, there exists $g$, with $g>pg$, such that $\Sigma=gl$. Let $h$ be such that $p

If \( p_1 \) is the length of \( \mathscr{E}_1 \), then \( \frac{p_1}{p} = \frac{a_1}{a} \), from which it follows that \( p_1 < h \). Inscribe in \( \mathscr{E}_1 \) a polygon \( P_n \) having no points in common with \( \mathscr{E} \); using the same notations as in the first part, we have \( \Sigma_n = p_n l \); but since \( h > p_1 > p_n \), it follows that \( \Sigma_n < hl \), and therefore:

However, since \( s_1/s = a_1^2 / a^2 \), then \( s_1 < s + (\epsilon / 2) \); that is \( s_1 - s > s_n - s \), from which \( s_n - s < \epsilon / 2 \). By convexity we know that \( \Sigma_n + (s_n - s) + (s^{\prime}_n - s^{\prime}) > \Sigma \), hence \( \Sigma_n + \epsilon > \Sigma \), contradicting (46). After examining both cases, one concludes therefore that \( \Sigma = pl \).

We observe that the only surface areas considered up to that time were those of the right cylinder, the right cone, and the sphere (Archimedes, On the Sphere and the Cylinder). Thābit is the first to study the area of the oblique cylinder, which will be expressed in modern mathematics by an elliptic integral (the length $p$ of the base ellipse). This proposition marks a step towards determining the lateral area of a portion of an oblique cylinder bounded between two planes, whether parallel or not. This is precisely what Thābit establishes in the following propositions.

With the contributions of the Banū Mūsā and Thābit ibn Qurra, research in infinitesimal geometry rested on solid foundations and had made notable progress. These mathematicians provided important experiences from which a new beginning could emerge: the era of the heirs begins. These experiences are not limited to the theorems demonstrated – although they are numerous – but also include new methods and the rediscovery of older ones. We have seen the development of two types of methods. Already with al-Ḥasan ibn Mūsā and his brothers Muḥammad and Aḥmad, and with Thābit ibn Qurra in his last treatise, we have observed the emergence of methods based on geometric transformations.

On the other hand, we have seen that Thābit ibn Qurra reintroduces the concept of integral summation, certainly already present in Archimedes but absent in the treatises translated into Arabic. However, a thorough study of the two Archimedean texts translated into Arabic – On the Measurement of the Circle and On the Sphere and Cylinder – could have put a mathematician of Thābit ibn Qurra’s caliber on the path to this rediscovery. Furthermore, his integral summations are more general than those of Archimedes: the intervals he takes in the subdivisions are not necessarily equal. In his study of the paraboloid, where he also proceeds by integral summations, he does not consider cylinders of equal height, as Archimedes did, but rather a cone and frustums of cones whose heights are in the ratio of successive odd natural numbers (starting from 1). It was therefore foreseeable that in the following period, during which mathematical research intensified and developed rapidly, mathematicians would seek to improve their predecessors' demonstrations and to develop both the methods of integral summation and of geometric transformations.

The first to advance in this direction was al-Māhānī (d. ca. 880). He resumed the measurement of the parabola to provide a much shorter demonstration than that of Thābit ibn Qurra. Unfortunately, al-Māhānī’s text is unavailable – though it may still exist – so we cannot form a precise idea of it. The second heir was the grandson of Thābit ibn Qurra, Ibrāhīm ibn Sinān (296-335/908-946). A brilliant mathematician with a brief life, he stated that he could not accept that al-Māhānī “had conducted a more advanced study than that of my grandfather without any of us surpassing him.” He thus sought to provide a shorter demonstration not only than that of his grandfather, which, as we have said, required twenty lemmas, but also than that of al-Māhānī.

Ibrāhīm ibn Sinān therefore wrote the Kitāb fī misāḥat al-qiṭāʿ al-mukāfiʾ (On the Measurement of the Parabola), a brief treatise particularly concise and elegant. The central idea of his text, which he is keen to demonstrate from the outset, is that an affine transformation preserves the proportionality of areas. With that, only two lemmas and a single proposition are needed to complete the study.

then the following proportionality holds between the areas of triangles and the areas of polygons:

In the proof, he uses the transformation $T$ defined in the statement. This is an affine transformation, and he demonstrates that it preserves the ratio of areas in both the case of triangles and of polygons.

The second lemma reads as follows: the ratio between the areas of two parabolic segments is equal to the ratio between the areas of their associated triangles. In it, Ibn Sinān demonstrates that an affine transformation preserves the ratio between the area of a parabolic segment and that of an associated triangle, as well as the ratio between their homologous elements. The underlying property is, in fact, the invariance of area ratios (even for curvilinear figures) under affine transformations. To this end, he uses Archimedes’ axiom to demonstrate that it is possible to inscribe in a parabolic segment a polygon whose area differs, by as little as desired, from that of the parabola.

Once this is established, calculating the ratio between the area of a parabolic segment and its associated triangle no longer requires infinitesimal procedures, but only the observation that this ratio does not depend on the specific segment considered. This is precisely what he demonstrates in the following proposition: the area of a parabolic segment is equal to 4/3 the area of its associated triangle. Ibn Sinān’s strategy for improving his grandfather’s demonstration and reducing the number of propositions from twenty to three relies on the combination of affine transformations and infinitesimal methods.

Al-Qūhī (second half of the 10th century) also reduces the 36 propositions established by Thābit ibn Qurra for calculating the volume of a paraboloid of revolution to three. However, while Ibn Sinān follows the geometric approach – the method of transformations – present in Thābit ibn Qurra’s work, al-Qūhī follows the other path, also present in Thābit’s work, which leads him to rediscover the integral summations found in the works of Archimedes that were unknown to Arabic mathematicians.

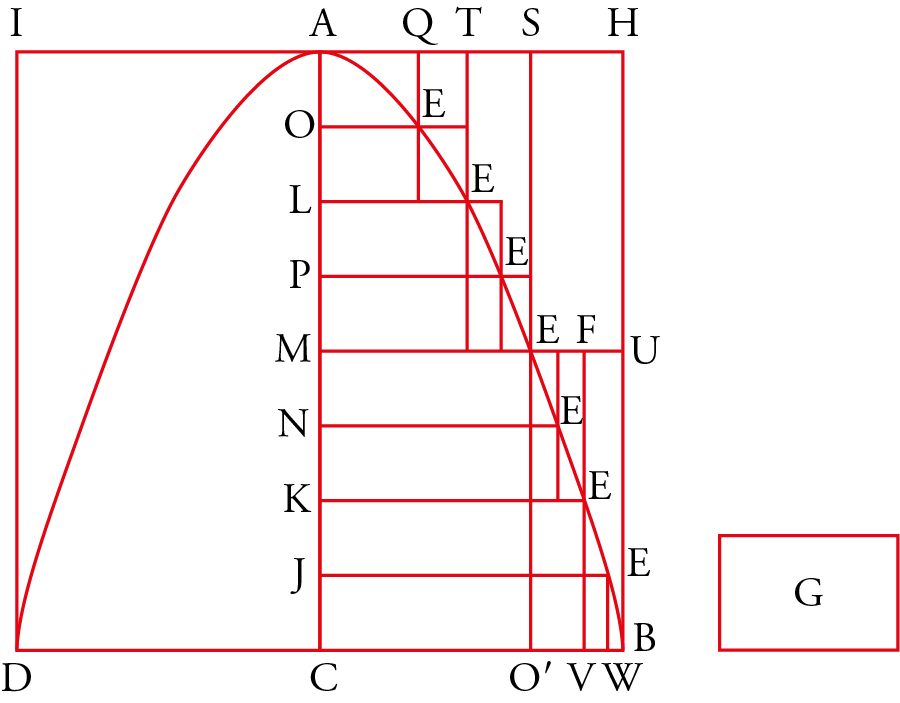

For the paraboloid of revolution, Archimedes considered cylinders of equal height, whereas Thābit ibn Qurra used adjacent frustums of cones, whose bases create a subdivision of the parabola’s diameter that generates the paraboloid. The segments of this subdivision are proportional to the odd natural numbers starting from 1, and the heights correspond to the segments in this subdivision. Al-Qūhī, in his effort to reduce the number of propositions demonstrated by Thābit, independently rediscovered integral summations as they appear in Archimedes. His method, in fact, differs from Archimedes’ only in a few details, particularly when demonstrating that the difference between inscribed and circumscribed cylinders can be made arbitrarily small. Here are the statements of his three propositions.

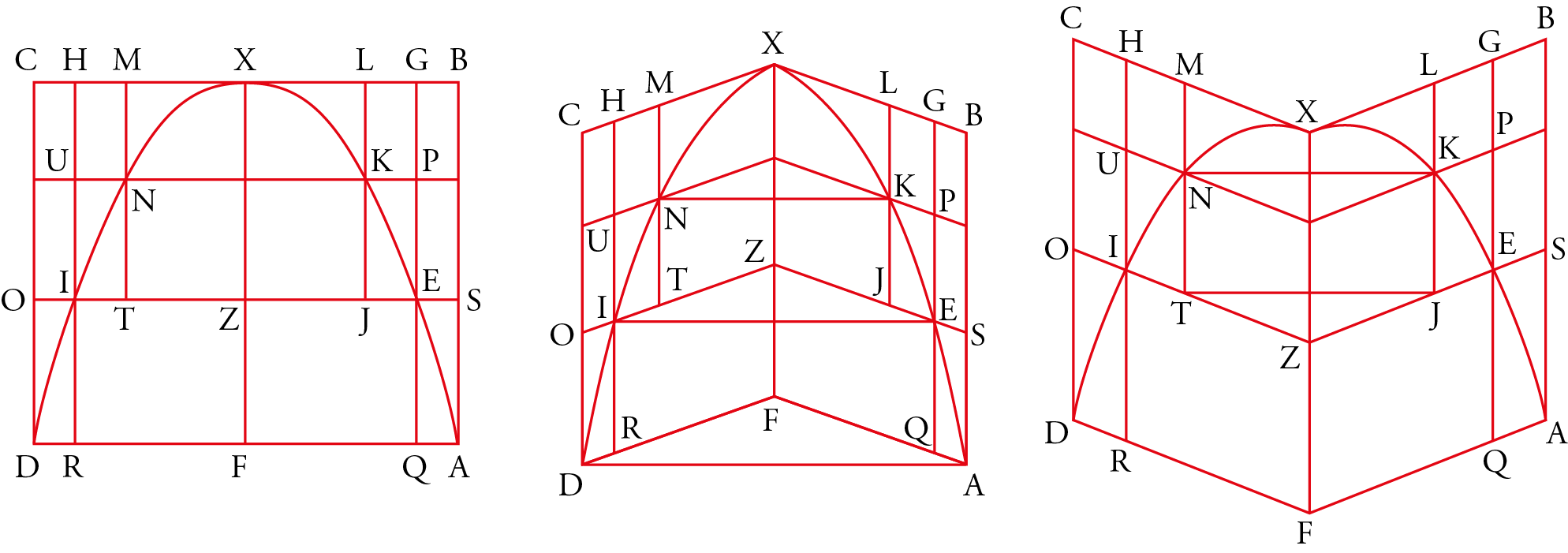

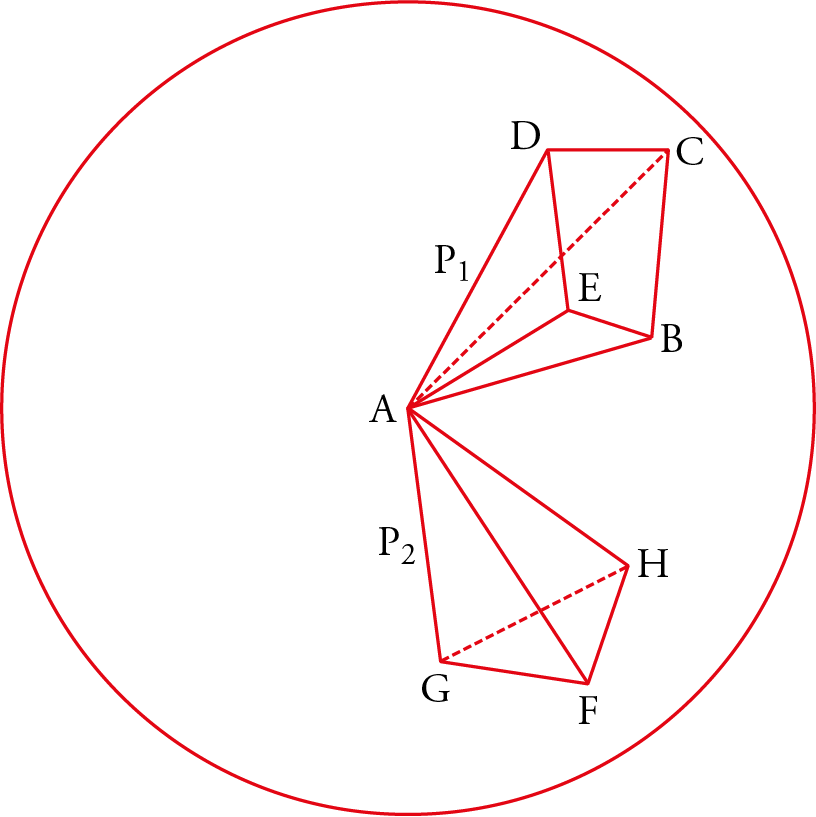

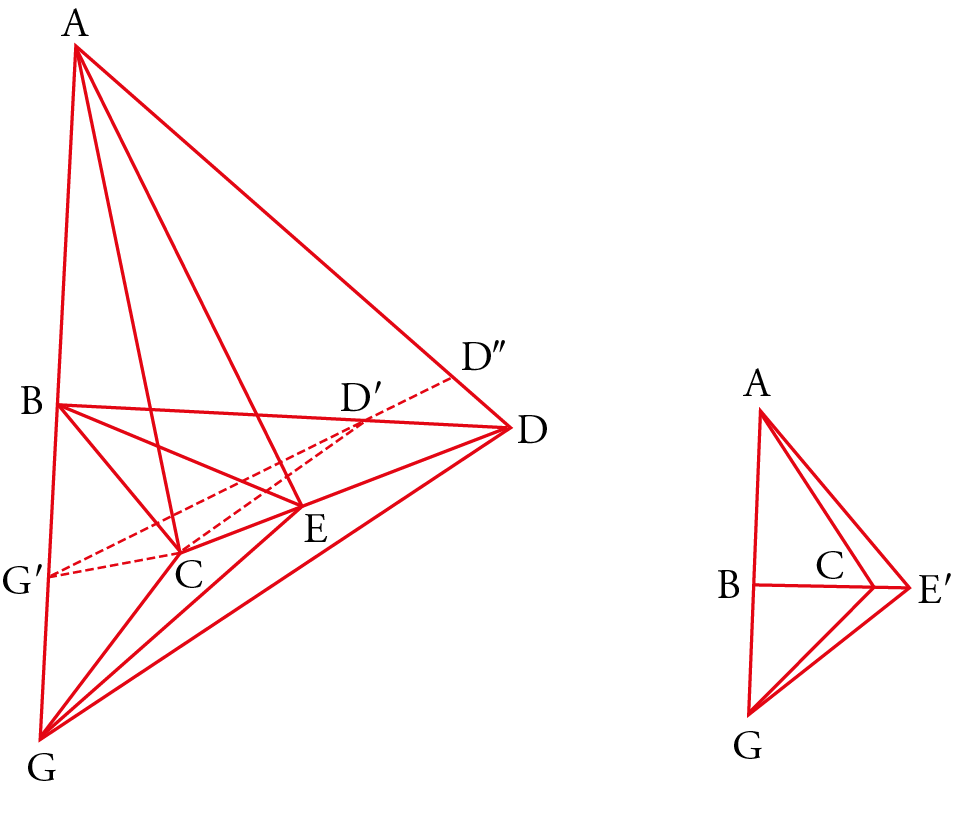

Proposition 1 is as follows. Given a paraboloid with axis $XF$ (fig. 12) and any subdivision with points of abscissa $(b_i)_{0 \le i \le n}$ and $b_0=0$, $b_n=XF$, let $(I_i)_{2 \le i \le n}$ be the volumes of the inscribed cylinders and $(C_i)_{1 \le i \le n}$ the volumes of the circumscribed cylinders associated with this subdivision, and let $V$ be the volume of the cylinder associated with the paraboloid. For all positive integers $n$, the following inequality holds:

Proposition 2 is as follows. Given a segment of a paraboloid between two arbitrary ordered surfaces, let $I$ and $C$ be the volumes of the inscribed and circumscribed cylinders, respectively. If this segment is cut by a surface equidistant from the two previous ones, we obtain two inscribed cylinders with volumes $I_1$ and $I_2$, and two homologous circumscribed cylinders with volumes $C_1$ and $C_2$. Then:

where $C-I$ is the volume of the ring $HGEC$, $C_1 - I_1$ the volume of the ring $NLMC$, and $C_2 - I_2$ the volume of the ring $LKGS$ (fig. 13). The proof of this proposition is as follows: starting with the subdivision of axis $XF$ with points of abscissa $(b_i)_{0 \le i \le n}$, with $(I_i)_{1 \le i \le n}$, $(C_i)_{1 \le i \le n}$, and $I_1 = 0$ as the volumes of the homologous cylinders, and then considering the sequence $(c_j)_{0 \le j \le 2n}$, with $c_0 = b_0$, $c_{2n} = b_n$, and $c_{2i+1} = (b_i + b_{i+1})/2$, and $(I^{\prime}_j)_{1 \le j \le 2n}$, $(C^{\prime}_j)_{1 \le j \le 2n}$ the volumes of the corresponding homologous cylinders associated with this new subdivision, the following relation holds:

In the third proposition, it is shown that if $P$ is the volume of a portion of a paraboloid and $V$ that of the associated cylinder, then $P = V/2$. Denoting by $(I_i^q)_{1 \le i \le n \cdot 2^q}$ and $(C_i^q)_{1 \le i \le n \cdot 2^q}$ the volumes of the cylinders associated with the subdivision, it follows from the previous proposition that:

for fixed $n$ and any positive integer $q$. This allows al-Qūhī, thanks to an extension of Proposition 1 from Book X of Euclid’s Elements, to assert that from a certain number of operations onwards:

or, in other terms, he shows that for every $\epsilon>0$, there exists an $N$ such that for every $q>N$, inequality (53) holds. But then:

and therefore:

Now, if $P = (V/2) + \epsilon$, it follows that $V/2 < \sum_{i=1}^{n \cdot 2^q} I_i^q$, which is impossible by Proposition 1. If instead $P = (V/2) - \epsilon$, one reasons similarly, since:

which implies:

and again, this is impossible in light of Proposition 1. Hence, we must conclude that $P=V/2$.

Al-Qūhī’s demonstration is quite swift, thanks to Proposition 1, which directly compares the sums of inscribed and circumscribed cylinders to the volume of the large cylinder, without needing to compute these sums explicitly, as Archimedes does by reducing the calculation to an arithmetic progression. The proof of this proposition is based on the inequalities $u_i - u_{i-1} < 2C_i$ and $u_i - u_{i-1} > 2I_i$, obtained by considering generic cylinders like $QGHR$ and $SBCO$ (fig. 12), which are neither inscribed nor circumscribed and thus are not given a priori.

Proposition 2 establishes that if the subdivision is refined by halving each interval, the excess of circumscribed over inscribed cylinders is halved. It plays the same role as Proposition 19 of Archimedes’ On Conoids and Spheroids.

Al-Qūhī’s method, through its use of integral summations, resembles that of Archimedes, though the application is somewhat different. It is as if al-Qūhī had independently rediscovered the use of integral sums.

Building upon the work of the Banū Mūsā and especially Thābit ibn Qurra, Ibn Sīnān follows a line of research that effectively combines geometric transformations and infinitesimal techniques, while al-Qūhī independently rediscovers, with the improvements we have seen, the methods of integral summation. In doing so, they not only offer their successors a new research perspective in infinitesimal geometry but also provide them with additional tools. These successors will not hesitate to revisit the problems addressed by their predecessors, adding new ones in the process.

The first to take this path appears to have been Ibn Sahl. He returned once again to the quadrature of the parabola; unfortunately, his treatise is still lost. However, based on his prominence among the mathematicians of the time, the various contributions we have reconstructed, and his familiarity with the work of al-Qūhī, we can surmise that he employed integral summation. This conjecture seems quite plausible not only for the reasons mentioned but also because Ibn al-Haytham (d. after 1040), his successor, revisits the measurement of the sphere and the paraboloid without referencing that of the parabola – as if that task had already been accomplished using the same method. It would fall to Ibn al-Haytham to bring this tradition, initiated a century and a half earlier, to its peak. With him, as we shall see, the calculation of curved surfaces and volumes reaches a level comparable to that found in other regions at the dawn of the seventeenth century.

He revisits the proof of the volume of the paraboloid of revolution, but he does not stop there: he also determines the volume of the paraboloid generated by the rotation of a parabola around an ordinate. Furthermore, he applies the same method to calculate the volume of the sphere. Before briefly presenting his method, we must recall a fundamental aspect of this mathematician's work, who was also a physicist and astronomer. While his predecessors, such as al-Qūhī, addressed the problem of infinitesimal determinations for curved surfaces and volumes – and while they also returned to the question of the center of gravity of such figures – Ibn al-Haytham would engage with the full spectrum of problems raised in this field: infinitesimal determinations, centers of gravity, isoperimetric problems, and solid angles. He also devoted attention to another topic, at least indirectly related to these: the study of lunes. Furthermore, in the course of these investigations and others, he encountered genuine differential problems. It is as if he intended to traverse the majority of the regions that would later constitute the continent of analysis.

Ibn al-Haytham’s treatise Maqāla fī misāḥat al-mujassam al-mukāfiʾ (On the Measurement of the Paraboloid) is structurally simple yet significant. In the introduction, in which he references the work of his predecessors Thābit ibn Qurra and al-Qūhī, he criticizes the former for “having followed a path lacking in structure and having limited his explanations to a long and laborious process” (p. 208), and the latter simply for having written a treatise that “contains only the proof for the measurement of one type of paraboloid” (ibid.). This introduction, which frames the work, is followed by an initial section devoted entirely to the arithmetic lemmas required for the demonstrations. He then addresses the sections on the paraboloid of revolution and the second type of paraboloid, concluding with a discussion of the method applied in this chapter.

He begins by demonstrating a general rule, via finite recurrence, for the calculation of the sums of the first $n$ integers raised to an arbitrary power iii. The rule is expressed as:

which allows him to establish an inequality necessary for the entire procedure:

The proof of this lemma is exceedingly long, yet it demonstrates both the depth of arithmetic investigation in this field and his mathematical virtuosity.

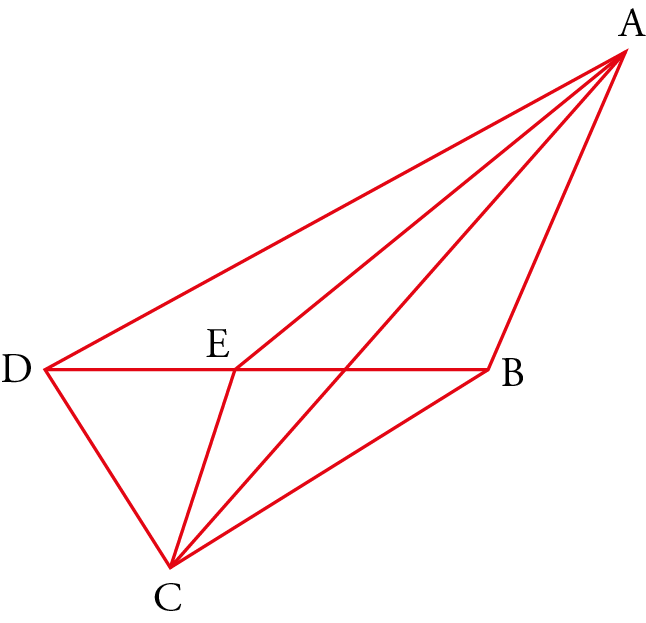

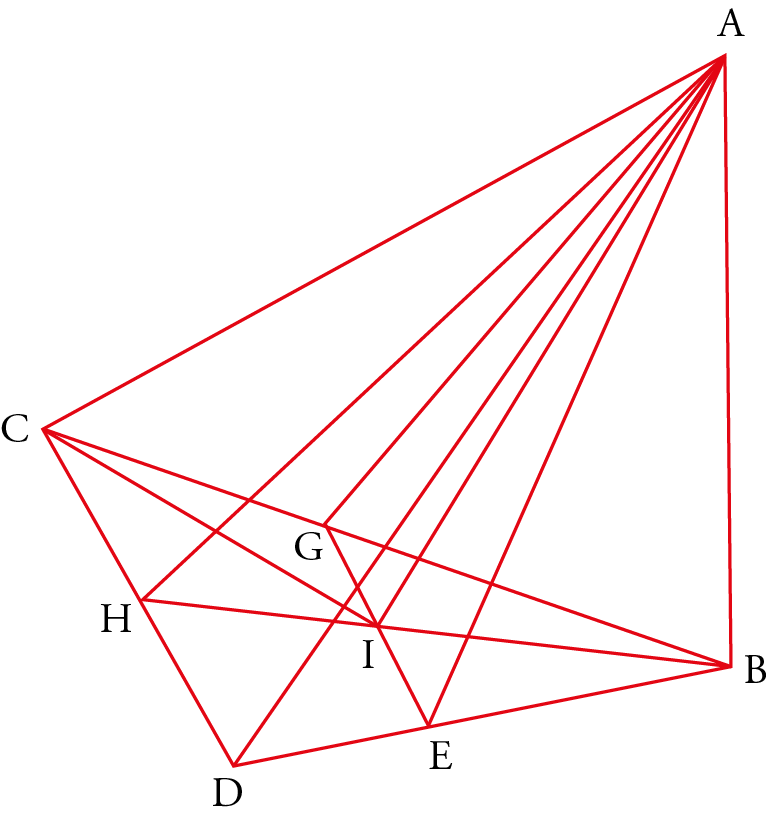

Ibn al-Haytham then proceeds to determine the volume of the paraboloid of revolution. He considers three cases, depending on whether the angle $\angle ACB$ is right, acute, or obtuse. Let us examine the first case in detail, following the author's process. If $V$ is the volume of the circumscribed cylinder and $v$ that of the paraboloid, the goal is to prove that $v = V/2$. Proceeding by contradiction, let us first suppose that $v > V/2$, i.e., $v - (V/2) = \epsilon$. Let $M$ be the midpoint of segment $AC$, and let line $MU$, parallel to $BC$, intersect the parabola at $E$ and line $BH$ at $U$. Let line $SEO^{\prime}$, parallel to $AC$, intersect $BC$ at $O^{\prime}$ and $AH$ at $S$. Denoting by $[EC]$ the solid generated by the rotation of surface $MCO^{\prime}E$, and analogously for the other solids, we have:

By iterating the construction from point $L$, the midpoint of $AM$, and then from point $K$, the midpoint of $MC$, we obtain:

therefore,

By iterating the construction at points $O$, $P$, $N$, and $J$ – the midpoints of segments $AL$, $LM$, $MK$, and $KC$ respectively – the sum of the eight solids will be equal to half of expression (62), that is, $\frac{\ 1\ }{8}V$. The procedure continues in the same fashion, that is, by subtracting solids of type (60) and (62) from the circumscribed cylinder. We thereby successively remove from $V$:

After a finite number of steps, we necessarily arrive at a remainder less than $\epsilon$, according to Lemma 1 of Book X of Euclid’s Elements (or Ibn al-Haytham’s theorem).

Let us suppose that the subdivision of the figure corresponds to the point at which the remainder is smaller than $\epsilon$. Let $V_n$ be the volume of the solids remaining after n$n$ steps; then $V_n < \epsilon$, and let $v_nv$ be the volume of the portion of these solids contained within the paraboloid. We have $v_n < V_n$ and thus $v_n < \epsilon$; by hypothesis, $v-v_n > \frac{\ 1\ }{2}V$. But by the properties of the parabola, we know:

which yields $CB^2 = 2EM^2$. Similarly:

which again results in $JE_j^2 + OE_o^2 = CB^2 = 2EM^2$. Analogously, we find $KE_k^2 + LE_l^2 = CB^2 = 2EM^2$, and so on. Denoting the points on the parabola as $E_0 = A, E_1, E_2, \cdots, E_n = B$ (with $n=2^m$) corresponding to points on the axis $F_0 = A, \cdots, F_{n/2} = M, \cdots, F_n = C$, we obtain:

and hence:

Let $S_i = \pi (\overline{E_iF_i})^2$ be the areas of the disks of radius $E_iF_i$ for $(1 \le i \le n-1)$, and let $S_n$ be the area of the disk of radius $E_nF_n = BC$. Then:

Let $W_i$ be the volume of the cylinders with base $S_i$ and height $h = \frac{\ 1\ }{n}AC$, and $W_n$ the volume of the cylinder with base $S_n$ and height $h$. Then:

Now,

since $V = nW_n$, so $\sum_{i=1}^{n-1} W_i < \frac{\ 1\ }{2}V$. But we also have $\sum_{i=1}^{n-1} W_i = v-v_n > \frac{\ 1\ }{2}V$, which is impossible. Therefore, $v \le \frac{\ 1\ }{2}V$.

Next, suppose that $v < \frac{\ 1\ }{2}V$, that is $v + \epsilon = \frac{\ 1\ }{2}V$, and proceed as before. We again remove half of the volume of the cylinder, then half of the remainder, until the remaining volume $V_n$ is less than an arbitrarily small $\epsilon$. Let $u_n$ be the portion of $V_n$ external to the paraboloid. Then $u_n < V_n < \epsilon$, and so $v + u_n < \frac{\ 1\ }{2}V$. But:

Also, $\sum_{i=1}^{n-1} W_i = \sum_{i=1}^{n} W_i - W_n$, so:

Hence, $\sum_{i=1}^n W_i > \frac{\ 1\ }{2}V$, which is again impossible. Therefore, $v \ge \frac{\ 1\ }{2}V$.

Thus, we have shown that $v = \frac{\ 1\ }{2}V$ in the case where $\angle ACB$ is a right angle. Ibn al-Haytham addresses the other two cases, where $\angle ACB < \pi/2$ and $\angle ACB > \pi/2$, by applying an affine transformation: oblique axes are converted into rectangular axes. More precisely, he maps each point of the figure in either of the two cases to the corresponding point in the first case, using the preservation of relationships within the figures. This is therefore a method that combines integral summation and the method of exhaustion, supported by a solid arithmetic foundation.

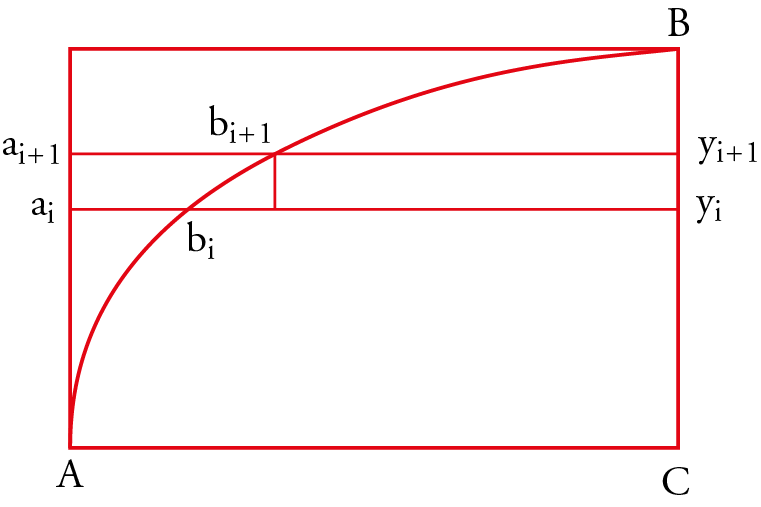

Ibn al-Haytham’s method becomes particularly evident in his treatment of the second kind of paraboloid – namely, that obtained by rotating a parabola around an ordinate. To better highlight the nature of his approach, let us describe his study using a different notation. Consider the paraboloid generated by rotating the sector $ABC$ of the parabola $x = ky^2$ about the ordinate $BC$. Let $AC=c$ and $BC=b$. Let $\sigma_n = (y_i)_{0 \le i \le 2m}$ with $2m=n$, a subdivision of the interval $[0, b]$ with step $h=b/n$. Let $M_i$ be the points on the parabola with ordinate $y_i$ and abscissa $x_i$, and define $r_i = c - x_i$ for $0 \le i \le 2^m = n$. It follows that $r_i = k(b^2 - y_i^2) = kh^2(n^2 - i^2)$. Denoting by $I_n$ and $C_n$ the volumes of the inscribed and circumscribed cylinders, we have:

and by inequality (59):

where $V = \pi k^2 b^4 \cdot b$ is the volume of the circumscribed cylinder. Still using a modern formalism not present in Ibn al-Haytham’s original, we can express the calculation as follows. Since the function $g(y) = ky^2$ is continuous on $[0, b]$, denoting the volume of the paraboloid by $v(p)$, we have:

that is:

thus:

yielding:

where $V$ is again the volume of the circumscribed cylinder.

Finally, Ibn al-Haytham investigates the behavior of solids approximating the paraboloid from the outside as the number of subdivision points increases. He essentially addresses the problem of the variation in the ratio between the inner and outer infinitesimal solids approximating the paraboloid. While in the case of the first kind of paraboloid both solids have the same volume, this is not the case for those of the second kind. Denoting the volumes of the inner and outer approximating solids by $v_n$ and $u_n$ respectively, he proves that:

Let $u(m)$ and $W(m)$ be the corresponding values at the $m$-th subdivision (with $n = 2^m$). He demonstrates that:

hence the ratio increases with finer subdivisions. This reflects a clearly infinitesimal orientation and, to some extent, a theory of functions. The goal is explicit: to understand the asymptotic behavior of mathematical objects by studying their variation.

Following the treatise on paraboloids, Ibn al-Haytham addresses the volume of the sphere in another treatise titled Qawl fī misāḥat al-kura (On the Measurement of the Sphere), in which he applies the same method. He begins similarly, by introducing the necessary arithmetic lemmas. He first recalls:

and establishes the inequality:

Using the same method as before, he proves that the volume of the sphere equals two-thirds that of the circumscribed cylinder. Let us now examine the integral approach underpinning this method. To determine the volume of revolution about a given axis, he considers inscribed and circumscribed cylindrical slices whose axis coincides with that of the solid of revolution. This yields lower and upper approximations of the volume using integral sums (Darboux sums) corresponding to the function that generates the solid.

For example, in the case of the sphere:

where the function $f$ is monotonic and:

for $x_{i-1} \le x \le x_i$, with $m_i$ and $M_i$ being values at the endpoints of the $i$-th subinterval. He then uses the inequalities $I_n < v < C_n$, and shows that for any $\epsilon > 0$, there exists an $N$ such that for all $n \ge N$, we have $v - I_n < \epsilon$ and $C_n - v < \epsilon$, demonstrating that $I_n \to v$ and $C_n \to v$. In other words, the volume $v$ equals the integral $\int_0^R f(x)\, dx$. Ibn al-Haytham’s calculation thus effectively corresponds to a simple Cauchy-Riemann integral.

This mathematical equivalence, however, should not obscure the following question: why did Ibn al-Haytham, after determining volumes by means of this integral, never provide a general method for determining other volumes and areas? To answer this question satisfactorily, it is not enough to invoke the specific needs of Ibn al-Haytham. In his mathematical, optical, and astronomical works, he never required the calculation of the volume of a paraboloid – nor, for instance, of a hyperboloid of revolution. The absence of such a general method must therefore be attributed to the method itself.

Indeed, one may observe that, like his predecessors in dealing with areas, Ibn al-Haytham always appeals to another solid with a known volume against which to compare the given solid. This prior knowledge of the comparison solid is not an artifice of the method: it allows Ibn al-Haytham, as it did his predecessors, to perform an effective, direct, and exact calculation of the limits of the corresponding Darboux sums. Yet in the general case, such comparison solids may not exist. This renders the mathematical tools employed by Ibn al-Haytham inadequate for effectively computing Darboux sums. It is therefore a genuine internal limitation that characterizes his method.

Nonetheless, one must be careful not to overstate the significance of this limitation – a limitation that would later disappear with the more extensive development of arithmetic calculus. If the use of a reference volume well characterizes the Archimedean tradition, the growing arithmetic orientation in the Arab mathematical tradition shows that it was no longer strictly a matter of Archimedean inheritance. Ibn al-Haytham was guided not only by geometry but already by arithmetic; his lemmas arise from an arithmetical conception of geometric figures.

In this study, one can already observe the development of the tools and techniques of this branch of mathematics in the Arabic world. We have seen how Ibn al-Haytham, in his investigations on the paraboloid, attained results later attributed by historians to figures such as Kepler and Cavalieri. These inquiries, however, came to a halt – most likely due to the absence of an effective symbolic notation.

Among the problems concerning the determination of the areas of curved surfaces, the exact quadrature of the 'lunules' – surfaces bounded by two arcs of a circle – is one of the oldest. According to later sources such as Simplicius, the 6th-century commentator of Aristotle, the problem dates back to Hippocrates of Chios in the 5th century BCE. In his commentary on Aristotle’s Physics, Simplicius quotes a long passage from Eudemus, a disciple of Aristotle, which contains the results and methods of Hippocrates. This passage, which also raises several philological and historical questions, is the only known source for the history of this problem in Greek mathematics. It also indicates the context in which the problem of the quadrature of certain lunules was posed, in this case as part of the problem of squaring the circle.

About five centuries after Simplicius, Ibn al-Haytham repeatedly returned to this question, initially in connection with the quadrature of the circle, and later as a problem in its own right. In fact, he revisits it in three treatises, only one of which – the one on squaring the circle – has been studied until now, while another short one is dedicated to the quadrature of the lunules. Later, he returned to the subject, obtaining results that would be attributed to mathematicians of the 17th and 18th centuries. The lack of awareness of Ibn al-Haytham’s work, particularly of this latter treatise, has led historians to make, in complete good faith, erroneous assessments of his contributions to these investigations.

Everything suggests that Ibn al-Haytham’s starting point was the text attributed to Hippocrates of Chios. In his first treatise, Qawl fī ’l-hilāliyyāt (Treatise on the Lunules), he begins by saying: “when I considered [...], the figure of the lunules equal to a triangle, mentioned by the ancients [...]”. Later, in a second treatise, Maqāla mustaqṣā fī ’l-ashkāl al-hilāliyya (Exhaustive Treatise on the Figures of the Lunules), Ibn al-Haytham recalls his earlier book by stating: “I composed a short treatise on the lunules according to particular methods” (Rashed 1993a, p. 102). The results of Hippocrates of Chios are also mentioned in his works. Did Ibn al-Haytham become familiar with them through Simplicius’s commentary on Aristotle’s Physics, which might have been translated into Arabic at the time? We have no documents that allow us to answer this question precisely. In his first work, Ibn al-Haytham refers to the ‘ancients’, but does not reproduce any of Hippocrates’s figures. Nevertheless, his first result slightly generalizes a proposition by Hippocrates, cited by Simplicius based on a text by Alexander of Aphrodisias; this significantly complicates the problem. It is proposition 3, which also appears in his work on squaring the circle (Qawl fī tarbīʿ al-dāʾira), and in his second treatise (prop. 8). In any case, let us now turn to Ibn al-Haytham’s two works.

The method adopted in both consists of studying lunules bounded by arbitrary arcs and seeking equivalences between surfaces. The author introduces circles equivalent to sectors of circles given in the problem and expressed as fractions of the latter. He justifies the existence of the introduced circles, which he adds to or subtracts from polygonal surfaces to obtain a surface equivalent to that of a lunule, or the sum of two lunules.

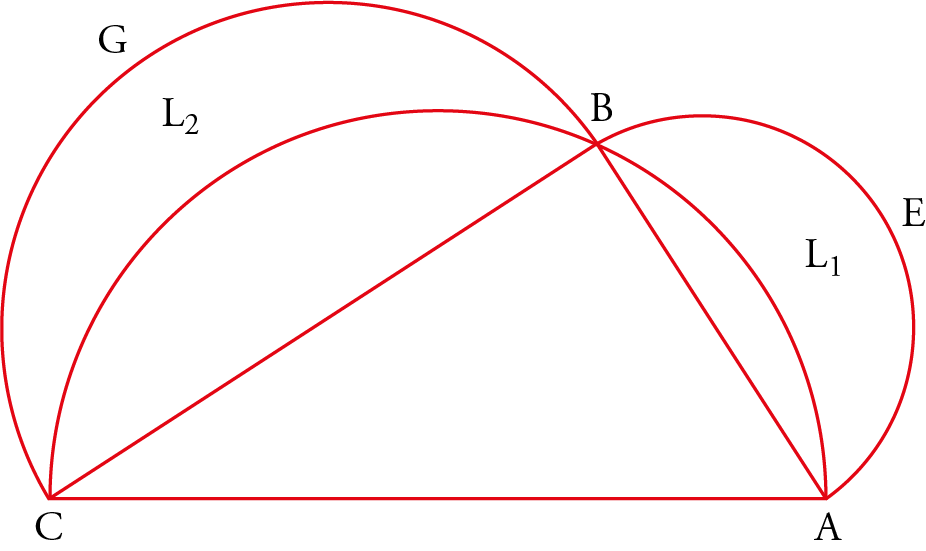

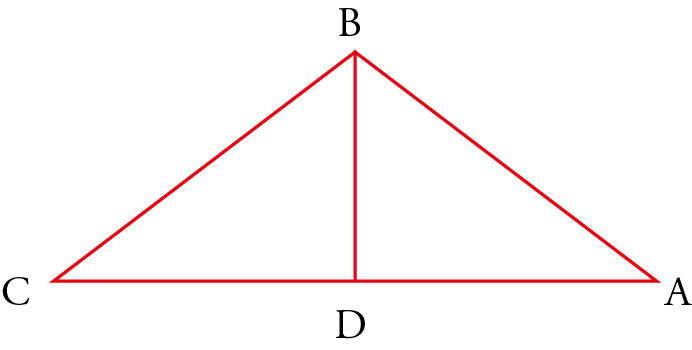

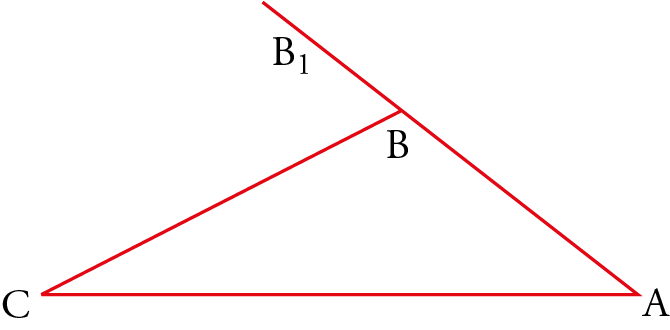

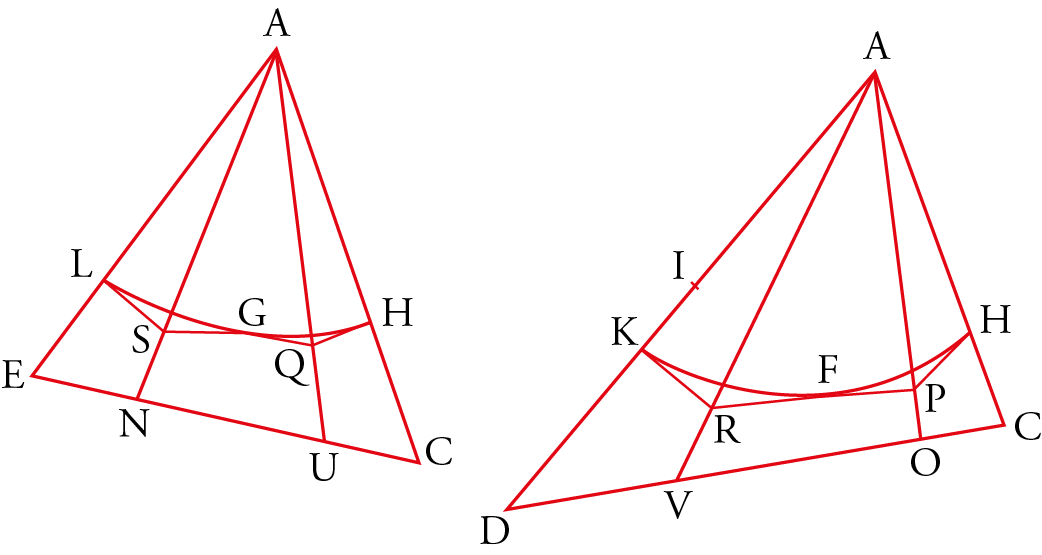

In the first short treatise, in propositions 1, 2, and 5, he begins with a semicircle $ABC$ to study lunules $L_1$ and $L_2$ bounded by an arc $AB$ or $BC$ and a semicircle (fig. 18). He assumes that the arc $AB$ is equal to one-sixth of a circle and establishes the following results:

where $L_3$ is a lunule similar to $L_1$ such that $L_3 = L_1$, and $\mathscr {C}(ABC)$ and $\text{tr}(ABC)$ denote respectively the circle $ABC$ and the triangle $ABC$.

In proposition 3, he slightly generalizes the demonstration of the result of Hippocrates of Chios by considering an arbitrary point B on the semicircle $ABC: L_1 + L_2 = \text{tr}(ABC)$; and in proposition 4, he studies the ratio between two similar lunules. It should be noted that in these propositions the lunules L₁ and L₂ involved are those associated with the three semicircles $ABC$, $AEB$, and $BGC$.

This first treatise thus follows in the footsteps of the research of Hippocrates of Chios. The same applies to the part concerning the lunules in the work Fī tarbīʿ al-dāʾira. Like Hippocrates, Ibn al-Haytham uses the proportionality between the area of a circle and the square of its diameter, and the Pythagorean theorem. In both cases, the lunule associated with the isosceles right triangle is studied. Even though Ibn al-Haytham’s reasoning is somewhat more general, this generalization does not fundamentally alter the similarity between his procedure and that of Hippocrates. For the sake of completeness, it should be noted that what is important in Fī tarbīʿ al-dāʾira is not the results on lunules, which he studies as in the first treatise, but the distinction he establishes between the existence of a square equivalent to a circle – that is, in modern terms, the existence of a transcendental ratio – and the constructibility of this square or ratio.

The situation is very different in the second treatise, Maqāla mustaqṣā fī ’l-ashkāl al-hilāliyya. Not only does he obtain more general results here, but the procedure is not the same. He returns to the problem of the quadrature of the lunules, moves it to the plane of trigonometry, and seeks to deduce the different cases as various properties of a trigonometric function that would be recognized much later by Euler. From the outset, he explicitly acknowledges that the calculation of the areas of lunules involves sums and differences of areas of circular sectors and of triangles, the comparison of which requires the comparison of ratios between angles and ratios between segments. For this reason, he begins by establishing four lemmas concerning triangle $ABC$, right-angled at $B$ in the first lemma and with an obtuse angle in the other three (figs. 19, 20), which now show that the essential point of the research has become the study of the function

The first lemma states the following. Given two convex polygons $A = (A_0, A_1,\cdots, A_n)$ and $B = (B_0, B_1,\cdots, B_n)$, let the points $A_1,\cdots, A_{n-1}$ be projected onto $A_0A_n$ parallel to $A_{n-1}A_n$ at points $Ac_1,\cdots, A^{\prime}_{n-1} = A_n$, and the points $B_1,\cdots, B_{n-1}$ onto $B_0B_n$ parallel to $B_{n-1}B_n$ at points $B^{\prime}_1,…, B^{\prime}_{n-1} = B_n$. If:

a) If $0 < C < \pi /4$ and $A < \pi /2$, then $(\sin^2 C)/C < 2/ \pi < (\sin^2 A)/A$; it is clear that if $C = A = \pi /4$, then $(\sin^2 C)/C = (\sin^2 A)/A = 2/ \pi$.

b) Let $\pi – B=B_1$; if $C < \pi /4$ and $B_1 < \pi /2$, then $(\sin^2 C)/C < (\sin^2 B_1)/B_1$.

c) If $A \le \pi /4$, then $(\sin^2 A)/A < (\sin^2 B_1)/B_1$.

d) Here he proposes to study the case $A > \pi /4$. The study, however, is incomplete: Ibn al-Haytham demonstrates that, given $A$, one can find $B_0$ such that

This incomplete study seems to have prevented him from seeing the equality

\begin{equation} \frac{\sin^2{A}}{A}=\frac{\sin^2{B_1}}{B_1} \ \text{.} \end{equation}It will be noted that these lemmas, by linking the problem of the quadrature of the lunules to trigonometry, change its status and allow the various particular cases to be unified. But the previously mentioned incompleteness conceals the possibility of the existence of squarable lunules. Let us now briefly turn to the propositions of Ibn al-Haytham’s second treatise.

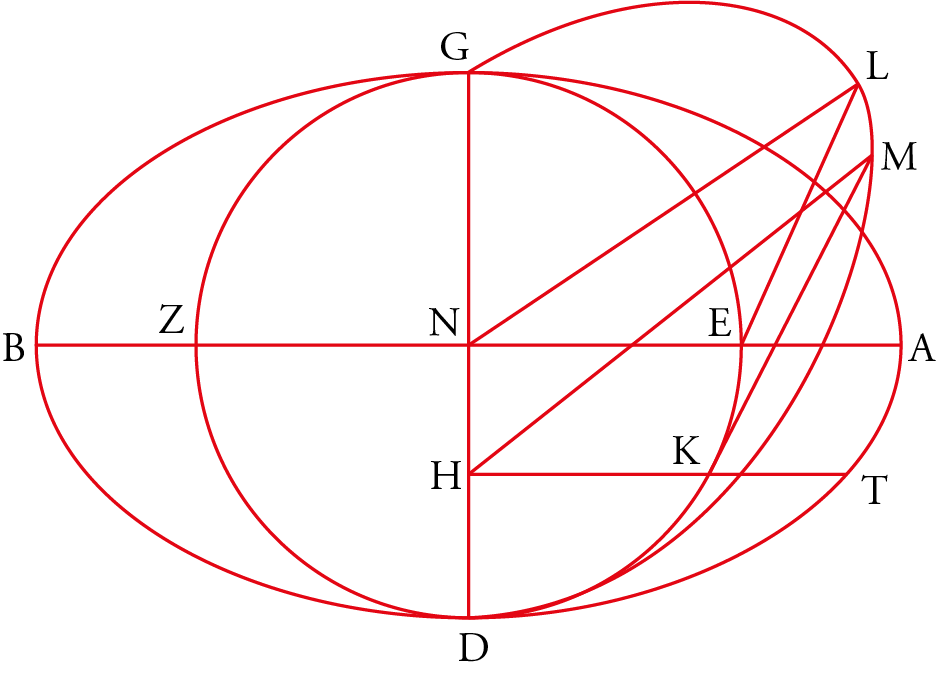

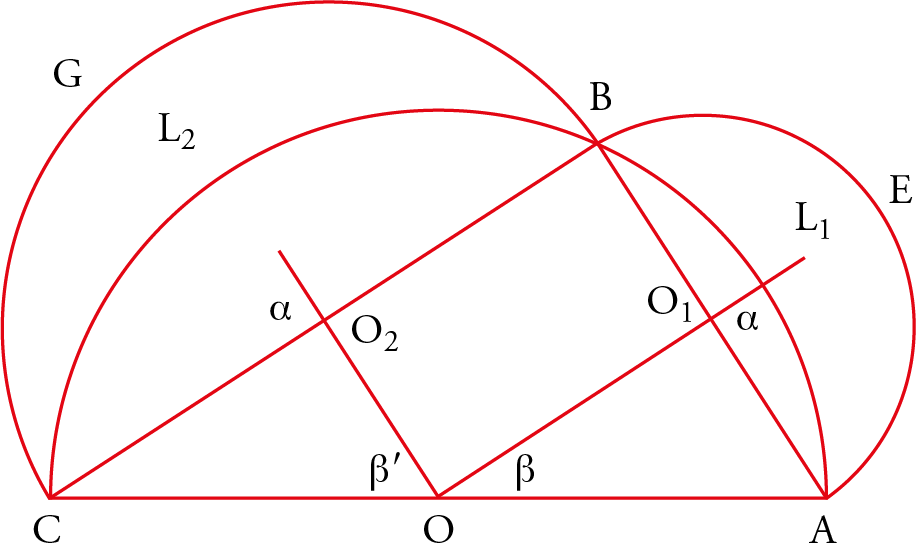

In nine propositions, from 8 to 16, the lemmas are paired, and in all cases, the three arcs $ABC$, $AEB$, and $BCG$ are similar. Let $O$, $O_1$, and $O_2$ be the centers of the corresponding circles (fig. 21).

Let us set $\angle AOC = \angle AO_1B = \angle BO_2C = 2\alpha, \angle AOB = 2\beta$, and $\angle BOC = 2\beta^{\prime}$, with $\beta \le \beta^{\prime}$ and $\beta - \beta^{\prime} =\alpha$.

The lunule $L_1$ is characterized by $(\alpha, \beta) $ and the lunule $L_2$ by $(\alpha, \beta^{\prime})$. The case $\alpha =\pi /2$ is considered, and the following propositions are established:

1. For every pair $(\beta, \beta^{\prime})$ such that $\beta + \beta^{\prime}= \pi /2$, we have $L_1 + L_2 = \text{tr}(ABC)$;

2. For $\beta = \beta^{\prime}= \pi /4$, we have $L_1 = L_2 = \text{tr}(ABC)/2$; in this case, $\alpha / \beta = 2/1$, and this is the only squarable lunule studied by Ibn al-Haytham. For $\beta < \beta^{\prime}$ we have:

where the circle $N$ depends on the ratio $\alpha / \beta$.

3) For $\beta = \pi /6$, we have $L_1 = (1/2)·\text{tr}(ABC) - (1/24) \mathscr {C} (ABC)$; in this case, $\alpha / \beta = 3/1$. For $\beta^{\prime} = \pi /3$, we have $L_2 = (1/2)·\text{tr} (ABC) + (1/24)·\mathscr {C} (ABC)$, and in this case $\alpha / \beta = 3/2$.