The seventeenth century was a period of intense change, marked by new discoveries and a drastic revision of the European conception of Nature and our place in it. Later chapters in this history will chronicle the details of these changes in the different domains of inquiry, and at the end we will address the question as to whether or not we can call what happened a genuine revolution. But in this chapter I would like to address some of the large-scale aspects of these changes, and outline in broad strokes some of the main developments that will be examined in more detail later in this history.

In this context, it is important to remember that the baseline throughout much of the century, in virtually every domain of the study of Nature, remained Aristotelian natural philosophy. It is there that we must begin, with Aristotelian science and the challenges to it, both before and during our century. But the transformation of the project of understanding Nature went even deeper than that. In this chapter we shall also examine changing attitudes toward history, toward mathematics and experiment, and toward certainty and probability. By the end of the century, the world was a very different place, both with respect to Nature itself and with respect to those who investigated it.

The natural philosophy of Aristotle was at the center of European intellectual consciousness from the late thirteenth century to the late seventeenth and even into the eighteenth century. By the dawn of the seventeenth century, it had become a central part of the curriculum at all of the schools in Europe, both Catholic and Protestant. Virtually all, Catholic and Protestant, Northern or Southern European, could agree with the Jesuit Ratio studiorum of 1586, their manual of instruction, in holding that, at least in the classroom, “in logic, natural philosophy, morals and metaphysics, the doctrine of Aristotle is to be followed” (Lukás 1986, p. 98). In this way, Aristotelian philosophy constituted the lingua franca of educated Europe.

The Aristotelian view of the natural world is nicely illustrated in Eustachius a Sancto Paulo’s Summa philosophiae quadripartita. First published in Paris in 1609, it was widely reprinted both in Catholic and Protestant countries and served as an introduction to natural philosophy for many a schoolboy. While we shall use Eustachius as an illustration of Aristotelian natural philosophy, his conception of the subject would have been widely shared by those who subscribed to the Aristotelian view.

Eustachius begins by specifying the subject matter of natural philosophy or physics, which is treated in the Physica, one of the four parts of the Summa: “objectum Physicae proprie loquendo esse Corpus naturale ut naturale” (Eustachius 1648, Physica, p. 112). Something is called a natural body to the extent that it contains a nature, that is, “quatenus continet principium motus et quietis” (ibid., p. 112). The implicit distinction here is between natural and artificial things. Natural things contain the sources of their own change. In this way, natural philosophy was contrasted with the sciences of the artificial, such as mechanics, which dealt with ways of accomplishing goals that go contrary to the natures of things, such as when we use a lever or a pulley to raise a heavy body some definite distance.

The Physica is then divided into three parts: De corpore naturale in genere, De corpore naturale inanimato, and De corpore animato. The first part treats the most general features of natural bodies, while the second and the third treat the features of particular bodies, both inanimate and living. The first part addresses the general features of the physical world, including form, matter and privation – the three Aristotelian principles of natural things – as well as the four causes, space, time, and motion. The second part then descends to particulars, where Eustachius treats celestial matter and the four elements (earth, water, air, and fire), as well as action, passion, generation, and corruption. Equally a part of physics is Eustachius’ treatment of living things in part three, where he treats the soul and all its faculties, as well as the separated soul.

Following the standard scholastic Aristotelian account, bodies for Eustachius are understood in terms of primary matter, substantial form, and privation. Primary matter is that which underlies change and remains when a body changes from one kind of thing to another. Substantial form, on the other hand, is that which characterizes a thing as the kind of thing that it is; it is what changes when a body becomes a thing of a different kind (in the living thing, the form was known as a soul). Privation is not really distinct from matter; it is the lack of some particular property in matter that allows that matter to acquire some property at a later time. In the strict Thomistic tradition, matter is pure potentiality and form pure actuality, and the one could not exist without the other. Eustachius followed the Scotist and Ockhamist traditions, though, and gave form and matter more of a capacity for independent existence. Also following the standard Aristotelian line, Eustachius denied the existence of vacuum or empty space.

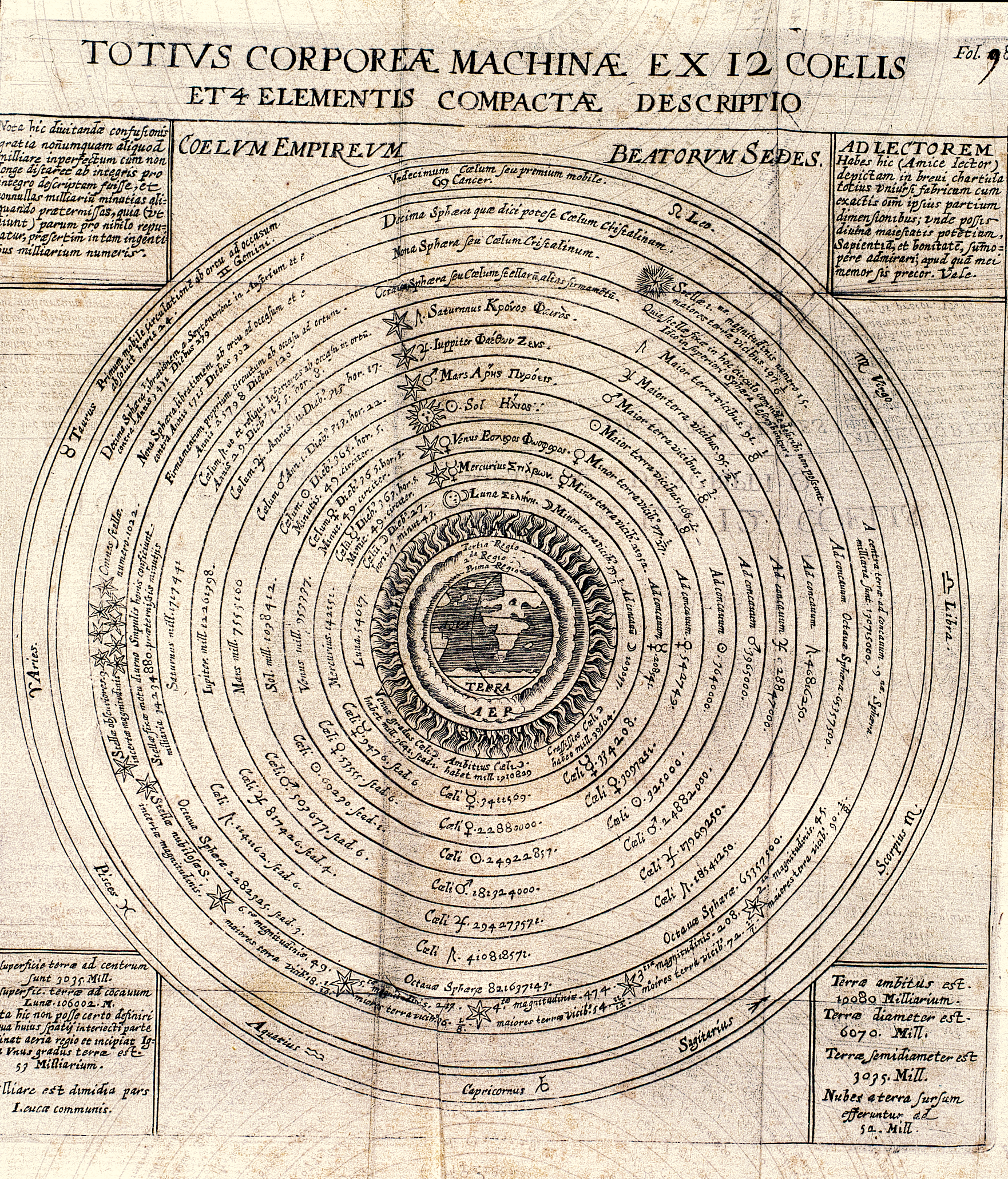

Also important was the Aristotelian conception of the specific kinds of bodies found within the world. In the sublunar world, the world below the sphere of the Moon, there were four elements: earth, water, air, and fire. By virtue of the form it has, each of the elements has a characteristic array of what were generally called primary qualities and motive qualities. The primary qualities are hot/cold and wet/dry. Earth, for example, was cold and dry, water cold and wet, air hot and wet, and fire hot and dry. In addition to the primary qualities, the elements had motive qualities, either heavy or light: earth and water, the heavy elements, had a tendency to fall downward toward the center of the world, and air and fire tended to rise and move away from the center of the world. Strictly speaking, though, these motive qualities derived from the fact that each of the elements had a proper place – earth at the center, then water, air, and fire respectively. When separated from that proper place, the elements had a tendency to move toward it. In Nature, though, the elements are rarely, if ever, found in their pure form. Normally they were thought to be mixed together, giving rise to bodies that had properties different from those of the elements that made them up. The very complex theory of mixtures gave rise to some of the most heated disputes in late medieval and early modern Aristotelianism. Because things in the sublunar world were made up of different elements capable of separating, the sublunar world was a world of things in flux, things generated as the elements combine, and corrupted as the elements separate.

Fundamentally distinct is the world of heavenly bodies. These bodies are made up not of the four elements, but of a fifth element, the “quintessence”. Celestial physics was taken to be altogether different from terrestrial physics. Rather than moving in rectilinear paths, celestial bodies move in perfect circles. Rather than a world of change, of generation and corruption, like the sublunar world, the celestial world was taken to be an unchanging world of perfection.

Though orthodox, the Aristotelian philosophy embodied in textbooks such as Eustachius’ Summa philosophiae quadripartita and taught in the schools was not without challenges. The Aristotelian philosophy was challenged almost as soon as it was introduced into the Latin West. Considered as a pagan philosophy, not easily reconciled with Christian thought, it was condemned in Paris on a number of occasions in the thirteenth century, culminating in the massive condemnation of 1277, where 219 propositions were prohibited.

By the late sixteenth century, there were a number of alternative systems of natural philosophy that challenged the Aristotelian worldview. Indeed, to those writing in the early seventeenth century, this looked like a genuine intellectual revolution. Already in the opening decades of the seventeenth century, conservative thinkers committed to Aristotelianism were complaining of those who rejected the received wisdom. In his great commentary on Genesis, the Quaestiones celeberrimae in Genesim (1623), Marin Mersenne identified as members of the sect, among others, Campanella, Bruno, Telesio, Patrizi, Hill and Basso, as well as Kepler, Galileo, Bacon and Gilbert. At roughly the same time, the popular Parisian professor Jean-Cécile Frey was lecturing to throngs of students, defending Aristotle against all opponents and excoriating the heterodox opinions of much the same cast of characters.

The sixteenth century had seen a variety of attacks on the Aristotelian hegemony. A very visible school of anti-Aristotelian thinkers was the so-called Italian Naturalists. These natural philosophers shared a general scorn for Aristotelian natural philosophy. In his De rerum natura (1565), Telesio rejected Aristotle’s conception of body in terms of matter and form, replacing it with a conception of the world grounded in heat and cold, immaterial (but natural) agents that enter into lifeless matter and thereby animate it. According to Telesio, virtually everything that we see around us in the physical world is the result of a struggle between these two fundamental and immaterial agents, which oppose each other.

Campanella’s thought represented something of a development and extension of Telesio’s ideas. Though Campanella began his career as a follower of Telesio in his Philosophia sensibus demonstrata (1591), in later years, he came to think that Telesio’s physical theory needed a deeper grounding. In his De sensu rerum et magia (1620) (and even later in his Universalis philosophiae, seu metaphysicarum rerum […] dogmata (1638)) he held that Telesio was wrong to think of hot and cold as natural agents and argued that their efficacy is traced back to God and the world soul. In contrast, light formed the foundation of Patrizi’s conception of the world in his Nova de universis philosophia (1591).

While Bruno was not altogether consistent as a thinker, there are a number of clear themes in his dense and complex writings. Bruno rejected the Aristotelian conceptions of God, substance, matter and form. In De la causa, principio et uno (1584), he held that God is the only substance, and all finite things are just aspects of God. Bruno did hold, in a sense, that the main principles of body are matter and form. However, he often treated them as coinciding with one another in a very non-Aristotelian way.

Telesio and Patrizi challenged Aristotelian conceptions of space and place and argued that space exists prior to everything, independent of body, an empty container which is, in part, filled by the physical world. The basic Aristotelian distinction between the heavens and the Earth was, of course, challenged by the Copernican system, first introduced in Copernicus’s De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (1543).

There were other attacks as well, most visibly from the direction of alchemy. Alchemists, particularly those in the school of Theophrast Bombast von Hohenheim, known as Paracelsus (1493–1541), mounted a concerted attack on the orthodox philosophy of the schools. While some alchemists saw what they were doing as consistent with the main lines of Aristotelianism, others saw themselves as replacing Aristotle with a new system of natural philosophy.

To conservatives such as Mersenne and Frey, all this had the appearance of a revolution, an attempt to overthrow Aristotelianism and replace it with something new. Mersenne saw this as presumptuous. In a famous passage, he wrote: “Aristote est un Aigle en Philosophie, les autres ne sont que comme des poussins, qui veu|lent voller avant que d’avoir des ailes” (Mersenne 1625, pp. 110–111). Others saw it as even worse. The French Aristotelian and astrologer, Jean-Baptiste Morin, reacting against a group of atomists who attempted a public attack on Aristotle, wrote: “il n’y a rien de plus seditieux et pernicieux qu’une nouvelle doctrine: Je ne dis pas seulement en Théologie, mais mesmes en Philosophie” (Morin 1624, ded. lett. p. 3).

Mersenne, Frey, and Morin could not have known that this was just the beginning of even more serious challenges to tradition. In 1620, Francis Bacon published his Instauratio magna (London, 1620), in which he outlined a complete renovation of all the sciences. As part of that work, he presented his Novum organum, a new experimental method for investigating the sciences and creating something genuinely new. At the same moment, the young René Descartes was working on his own method of investigation in his Regulae ad directionem ingenii, left unfinished at his death. Only a few years later he would publish his Discours de la méthode, where he would set out his own views on investigation and call for a new science. More important still, together with his discourse and exhortation, he would publish actual examples of the fruits of his method: a new geometry that united elements of traditional geometry with algebra, and the beginnings of the new mechanist science that was eventually to dominate scientific thought for the rest of the century.

In Descartes’ new natural philosophy, the matter and form of the Aristotelians was to be replaced with a world where bodies, both animate and inanimate, were to be understood on the model of machines. Galileo’s mathematicization of motion and coordinate elaboration of Copernicanism would further undermine the Aristotelian world, as would Pierre Gassendi’s revival of atomism, Thomas Hobbes’s materialism, and many other developments. By the end of the century, the universal genius Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz could recognize the emergence of a new philosophy, as did Mersenne and Frey before him: “Les fondateurs de la philosophie moderne sont Bacon, Galilei, Kepler, Gassendi et Descartes” (De la philosophie cartésienne, p. 1480).

The sixteenth-century innovators have been all but forgotten, and the seventeenth century has emerged as the century in which the new natural philosophy – in which modern science begins – takes shape. The details of the new science will be discussed in the chapters below: the rise of various forms of atomism and mechanism that provided an alternative to the world of matter and form that dominated the Aristotelian world, mathematical accounts of Nature, accounts of motion, space and vacuum that challenged Aristotelian conceptions, the breakdown of the distinction between the natural and the artificial, the celestial and the terrestrial, new accounts of life, etc. In this chapter, though, I would like to note some of the larger changes in the conception of the project of understanding the world that shaped these detailed changes.

One evident change that shaped the century was in the attitude toward novelty. Independent thought did not always have a good reputation. As we saw earlier, Morin argued that all novelty was dangerous. Similarly, the Oxford Latin Dictionary lists “subversive, seditious” as one of the meanings of the word novus, literally “new” in classical Latin, supported with quotations from Cicero, Suetonius, Tacitus, and Hirtius. Throughout the sixteenth century, novelty, innovation, and heterodox opinion were considered suspect, at least in some quarters. Benedictus Perera, an important teacher at the Jesuit Collegio Romano in Rome, expressed a generally held point of view when in 1564 he wrote that: “One should not be drawn to new opinions – that is, those which one has discovered – but one should adhere to the old and generally accepted opinions” (De modo legendi cursum philosophiae, p. 667). This view was reflected in the Jesuits’ Ratio studiorum, the rules governing their wide-flung network of schools. In the 1599 version of that document, teachers are warned that they must “flee novel opinions”, “even in matters which don’t endanger faith and piety”. The quotations could be multiplied and multiplied: to call a doctrine new, novel, or original was not necessarily a compliment.

But this was to change in the seventeenth century, when novelty seemed to become a positive value. Representative of this trend is Bacon’s Instauratio magna. Its title page shows a ship under full sail, heading between the Pillars of Hercules, out into the open ocean, representing the search for the new. Below the ship is a motto, taken from Daniel 12:4: “Multi pertransibunt et augebitur scientia”. The implication is that his book will usher in the age in which new discoveries will be made, and knowledge will be increased. Bacon begins the book with a critique of what has gone before:

For let a man look carefully into all that variety of books with which the arts and sciences abound, he will find everywhere endless repetitions of the same thing, varying in the method of treatment but not new in substance, insomuch that the whole stock, numerous as it appears at first view, proves on examination to be but scanty. And for its value and utility it must be plainly avowed that that wisdom which we have derived principally from the Greeks is but like the boyhood of knowledge, and has the characteristic property of boys: it can talk, but it cannot generate, for it is fruitful of controversies but barren of works. (Bacon 1620, p. 2)

Bacon’s response is bold: “to try the whole thing anew upon a better plan, and to commence a total reconstruction of sciences, arts, and all human knowledge raised upon the proper foundations” (ibid., proemium). There is no fear of novelty here. The past is to be rejected, and knowledge to be started anew.

One finds very much the same rhetoric in Descartes’ Discours de la méthode, where he sets out his own ambitious program for reforming the sciences. Like Bacon, Descartes was disappointed with what he had learned from the tradition:

Regarding philosophy, I shall say only this: seeing that it has been cultivated for many centuries by the most excellent minds and yet there is still no point in it which is not disputed and hence doubtful, I was not so presumptuous as to hope to achieve any more in it than others had done. And, considering how many diverse opinions learned men may maintain on a single question – even though it is impossible for more than one to be true – I held as well-nigh false everything that was merely probable. As for the other sciences, in so far as they borrow their principles from philosophy I decided that nothing solid could have been built upon such shaky foundations. (Descartes 1637, p. 10)

And like Bacon, Descartes hoped to start from the beginning and rebuild everything from the ground up. Comparing the body of accepted knowledge to a house built on unstable foundations or to a city that grew up in a haphazard way, he suggested that “regarding the opinions to which I had hitherto given credence, I thought that I could not do better than undertake to get rid of them, all at one go, in order to replace them afterwards with better ones, or with the same ones once I had squared them with the standards of reason” (Descartes 1637, p. 15). It is no surprise that when it came to rebuilding, relatively few of his former beliefs survived the process.

For Bacon and Descartes, as well as for their contemporaries who craved novelty, there were two main targets. One was the scholastic Aristotelianism that we discussed above. The Aristotelian doctrines taught in the schools represented the most visible examples of tradition and authority. But also at issue was the Humanist enterprise that was very prominent in sixteenth-century intellectual life, even among the scientists and mathematicians.

Humanism was a broad and somewhat diffuse intellectual movement that centered around the revival of the literature and culture of classical antiquity. Much of the effort was directed toward the revival of classical Latin language, rhetoric, and literature. But Humanism was very important to the sciences as well. In the course of the sixteenth century, Humanist scholars revived, edited, and studied important mathematical texts from antiquity, including the writings of Archimedes, Pappus of Alexandria, and others. Also important was the revival of ancient non-Aristotelian systems of natural philosophy. Justus Lipsius (Joost Lips, 1547-1606), for example, was important in reviving interest in Stoicism, including Stoic natural philosophy. Most important in this respect is Pierre Gassendi, perhaps the last of the scientific humanists. Much of his career was spent editing the Greek text of book X of Diogenes Laertius’ Lives of the Philosophers, which contains the main body of original texts of the ancient Greek atomist Epicurus. The publication of these texts, together with his learned and philosophical commentaries, was very important for reviving interest in atomism in seventeenth-century Europe.

But in the early seventeenth century, this dependence on the past was openly challenged. In the quotation given above, Bacon openly rejects the learning of the Greeks. Descartes, more generally still, rejects learning in general. In the Discours, he famously wrote: “since the sciences contained in books – at least those based upon merely probable, not demonstrative, reasoning – is compounded and amassed little by little from the opinions of many different persons, it never comes so close to the truth as the simple reasoning which a man of good sense naturally makes concerning whatever he comes across” (Descartes 1637, p. 14). Descartes’ solution, of course, was simply to reject what he learned in school, and turn toward the world and to himself for understanding the world.

Similarly indicative of this new spirit are the works of Galileo Galilei. In his Dialogo sopra i due massimi sistemi del mondo (1632), the character of Simplicio in the dialogue represents dogmatic Aristotelianism. In the course of the dialogue, Simplicio is constantly mocked for his dependence on Aristotle, in contrast with Salviati’s (Galileo’s) arguments from experience and reason, and the amateur Sagredo’s reasonable weighing of arguments. The lesson is clear: history and authority count for little if anything at all in the new world of the seventeenth century. At the end of the century, literary France will become embroiled in the so-called querelle des Anciens et des Modernes, where the literary merits of the ancients and moderns were battled out. But in the sciences, the issue had been settled years earlier. By the end of the century, it was safe to say that no respectable member of the Republic of Letters could fail to recognize the superiority of the modern natural sciences and mathematics over those of the ancients.

There are many disagreements about Aristotle’s view of the relation between mathematics and natural philosophy. But whatever exactly they were, as a matter of fact, mathematics played no substantive role in natural philosophy (physics) proper in the Aristotelian science of the late scholastic period. As outlined above, natural philosophy proper treated body in an entirely qualitative way, considered as a unity of matter and form, the elements, their mixtures and compositions into complex substances, and so on. But that is not to say that there were no mathematical sciences concerned with the physical world. In the later Aristotelian tradition, certain disciplines came to be grouped together as middle sciences or mixed mathematics, sciences connected both with physics and with mathematics. Representative here is Goclenius (Rudolph Göckel), in his Lexicon philosophicum of 1613. In his article on mathematics he notes three kinds of mathematics. In its most general sense, ‘mathematics’ means ‘discipline’, ‘doctrine’, ‘precepts’. In its second sense, it means geometry or arithmetic. But the third sense is the most interesting: he writes that [Mathematica] “non solum pro Arithmetica et Geometra sed etiam pro Astronomia, Optica, Musica, Mechanica, etc. accipitur” (p. 672). This notion of mathematics, mixed mathematics or the middle sciences, contained all of the sciences that treat Nature in mathematical ways.

It is important, though, to realize the distinction between the middle sciences and natural philosophy, properly speaking. In general, natural philosophy treats the ultimate causes of phenomena in Nature, in terms of their matter, form, and privation. The middle sciences, on the other hand, generally treat the phenomena, the results of those causes, in mathematical ways. Particularly interesting (and relevant to the radical changes in the seventeenth century) is the status of mechanics and its relation to physics. Natural philosophy (physics) treats natural things as they are in themselves, inquiring into their essences and the true causes of natural (physical) phenomena. But things in Nature don’t always do what we want them to do. This is where mechanics enters. Machines are not natural things, but artifacts; they are things constructed by us for the purpose of doing things that we want to have done. And mechanics is the science of such machines. The author of the Mechanica, attributed to Aristotle in the sixteenth century and therefore widely read and commented on, puts it in this way: “Our wonder is excited, firstly, by phenomena which occur in accordance with nature but of which we do not know the cause, and secondly by those which are produced by art despite nature for the benefit of mankind. Nature often operates contrary to human interest; for she always follows the same course without deviation, whereas human interest is always changing. When, therefore, we have to do something contrary to Nature, the difficulty of it causes us perplexity and art has to be called to our aid. The kind of art which helps us in such perplexities we call Mechanical Skill” (pseudo-Aristotle, Mechanica, 847a10f).

Mechanics treats artificial things, natural things as they are configured into devices for our benefit. In this way it is a supplement to physics proper: it treats at least certain kinds of things not treated in physics, in particular, artificial things, machines. And similarly, physics contributes to mechanics. Machines are, of course, made up of natural materials (wood, metal, ropes, etc.) which have their own natural properties. Mechanics must make use of those properties in explaining the behavior of machines. So, for example, heaviness plays a major role in explaining the simple machines (lever, screw, balance, etc.), all of which use human or animal force to overcome the natural effects of heaviness, and show the mechanic how to lift weights in different ways. Treatises on mechanics all assume that one is dealing with heavy bodies, bodies that tend to fall to the center of the Earth. The question of the cause of heaviness and free fall lay outside of the domain of mechanics and in the domain of physics. It was one of the premises that the mechanic could borrow from the distinct science of physics.

In the sixteenth century, mathematics and natural philosophy were quite distinct callings, whose practitioners lived in different worlds. But over the course of the seventeenth century, this changed radically. In 1610, in the wake of the success of his Sidereus nuncius, Galileo was invited to join the court of Cosimo de’ Medici in Florence. Given his interests in astronomy, optics, and mechanics, it would have been natural to appoint him as the mathematician to the Duke. But Galileo demurred. He wrote the following to Belisario Vinta, Cosimo’s Secretary of State:

Finalmente, quanto al titolo et pretesto del mio servizio, io desidererei, oltre al nome di Matematico, che S.A. vi aggiugnesse quello di Filosofo, professando io di havere studiato più anni in filosofia, che mesi in mathematica pura: nella quale qual profitto io habbia fatto, et se io possa et deva peritar questo titolo, potrò far vedere a loro Alt.e, qual volta sia di loro piacimento il concedermi campo di poterne trattare alla presenza loro con i più stimati in tal facoltà (Galilei, Ed. Nazionale, X, p. 353).

But Galileo was not the only one who saw physics and mathematics connected. Isaac Beeckman reported the following comment made by the young Descartes, with evident pride:

Dicit [i.e. Descartes] tamen se nunquam hominem reperisse, praeter me, qui hoc modo, quo ego gaudeo, studeiendi utatur, accurateque cum Mathematica Physicam jungat (Descartes, 1964-1974, X, p. 52).

When Beeckman’s writings appeared shortly after his death, it was under the title Mathematico-physicarum meditationum, quaestionum, solutionum centuria (1644). The very same year, Mersenne published a book with a very similar title, Cogitata physico-mathematica. Descartes, too, in a sense attempted to join physics and mathematics in a way more ambitious than Beeckman and even Galileo. For Descartes, everything in the world is to be understood in exactly the same way we understand machines. In his Principia philosophiae he wrote:

[N]ullum enim aliud, inter ipsa [i.e. artifacts] et corpora naturalia, discrimen agnosco, nisi quod arte factorum operationes, ut plurimum, peraguntur instrumentis adeo magnis, ut sensu facile percipi possint: hoc enim requiritur, ut ab hominibus fabricari queant. Contra autem naturales effectus fere semper dependent ab aliquibus organis adeo minutis, ut omnem sensum effugiant. (Pr. Phil., IV, p. 203)

And so it is no surprise that he wrote one correspondent that “toute ma physique ne soit autre chose que mécanique” (Descartes, 1964-74, II, p. 542). Though mathematics played little overt role in Descartes’ published physics, it is not unimportant that he identifies his physics with a recognized branch of mathematics. Thomas Hobbes, too, identified physics with mathematics. For Hobbes, indeed, physics is virtually identical with geometry.

Hobbes draws no distinction at all between the object of geometry and the object of physics. As a consequence, physical motion is, in essence, treated no differently than the motion of points, lines, and planes by which lines, surfaces, and solids are traced out; geometry for him is just the imaginary manipulation of bodies. In his later Elementorum philosophiae sectio secunda de homine (1658), Hobbes wrote:

Et quoniam, ne a posterioribus quidem ad priora ratiocinando procedi potest in rebus naturalibus, quae motu perficiuntur, sine cognitione eorum quae unam quamque motus speciem consequuntur; nec motuum consequentias sine cognitione Quantitatis, quae est Geometria; fieri non potest ut non aliqua etiam a Physico demonstratione a priore demonstranda sint. Itaque Physica, vera (inquam) Physica, quae Geometriae inmititur, inter Mathematicas Mixtas numerari solet. (Hobbes 1658, p. 60)

In Hobbes, what others considered before him to be mixed mathematics, has emerged as the true physics. From Hobbes’ point of view, it is not a matter of making the old physics mathematical. Rather, what had been considered mere mixed mathematics has taken over the mantle of physics. Much as Galileo tried to do earlier in the century, mixed mathematics presumes to speak now as philosophy.

It is hard to say exactly how mathematical physics was in these early programs. There was perhaps more of the ambition to combine physics and mathematics than there was any clear idea of how to do it. But by the end of the century, the two were inseparably linked. Sir Isaac Newton’s monumental Philosophiae naturalis principia mathematica (1687) provided a new paradigm for sciences of all kinds, where mathematics and physics were clearly linked. In that work, Newton used mathematical reasoning to establish the existence of a universal force that every body exerts on every other body inversely proportional to the square of the distance between the two of them. In this way, Newton used mathematical reasoning to infer the cause of such phenomena as planetary motion and falling bodies, a cause itself expressed in terms of a mathematical law. In this way Newton could be said to have united physics with a mathematical method and produced the true mathematical principles behind natural philosophy. A century earlier, a title such as Newton used, combining the immiscible terms ‘mathematics’ and ‘natural philosophy’ would have raised eyebrows and caused puzzlement. While not without controversy when Newton’s book was published, it quickly gathered admirers and imitators.

The appeal to experience and even to experiment were hardly new in the seventeenth century. Those concerned with understanding Nature from the ancients on down had made observations about the world that shaped their theorizing. This is particularly true in the domain of medicine, where the term empiric originally referred to a group of physicians (the so-called Empirici) who shunned theory and speculation and based their medical practice on experience. But it is also clear that there is something new about experience and its role in science in the seventeenth century.

For one thing, there was a great deal of new information about the natural world that was available to the seventeenth-century investigator. The title page of Bacon’s Instauratio magna, to which we referred earlier, shows a ship heading out of the Pillars of Hercules, from the Mediterranean into the open sea. This strongly calls to mind the voyages of discovery that had brought back knowledge of an entirely new world, new plants, new animals, new peoples, and an increased knowledge of the geography of the world. It even contributed to astronomy by bringing knowledge of the southern skies, which had been unknown to the ancient Greeks, and therefore to the medieval and Renaissance Europeans whose knowledge had been derived from that of their forebearers. Other new knowledge had come from technological advances, from the remarkable astronomical instruments of Tycho Brahe, from the new telescope and microscope, and from instruments such as Boyle’s air pump, which enabled people to experiment with environments that had never before been created on earth.

Experience was by no means foreign to the practitioners of the traditional Aristotelian sciences. This is especially true in the mathematical sciences, the middle sciences such as astronomy, optics and mechanics, as discussed above. Recent commentators have emphasized the extent to which early seventeenth-century Jesuit practitioners of these subjects were particularly concerned to ground their work in experience. But it was particularly among those who sought alternatives to Aristotelianism that experience gained importance, particularly as a way of undermining more orthodox Aristotelian approaches to Nature.

The appeal to experience and experiment was central to the alchemical philosophies that were arising to challenge the dominant Aristotelianism. In a famous passage of the Idea medicinae philosophicae (1571), the Paracelsian physician Peder Sørensen (Petrus Severinus) writes:

[...] sell your lands, your houses, your clothes and your jewelry; burn up your books. On the other hand, buy yourselves stout shoes, travel to the mountains, search the valleys, the deserts, the shores of the sea, and the deepest depressions of the earth; note with care the distinctions between animals, the differences of plants, the various kinds of minerals, the properties and mode of origin of everything that exists. Be not ashamed to study diligently the astronomy and terrestrial philosophy of the peasantry. Lastly, purchase coal, build furnaces, watch and operate with the fire without wearying. In this way, and no other, you will arrive at a knowledge of things and their properties. (p. 39)

For the alchemist, experience was essential to discovering the way the world is. But the dominant advocate for experience in science in the seventeenth century was undoubtedly Sir Francis Bacon. As we discussed earlier, Bacon’s ambition, as expressed in his Instauratio magna, was to reform all knowledge. And to do so, he argues, we must start with a direct appeal to nature itself. He writes: “Those […] who aspire not to guess and divine but to discover and know, who propose not to devise mimic and fabulous worlds of their own, but to examine and dissect the nature of this very world itself, must go to things themselves for everything” (Bacon 1620, p. 23). And going to “things themselves” – a rebus ipsis – means, of course, going to experience.

Bacon outlines the procedure for using experience and experiment in his Novum organum, an alternative to the Aristotelian Organum, or collection of logical and methodological treatises, published as the second part of the Instauratio magna in 1620. The first step of Bacon’s new method is simply the collection of experiments and observations. Bacon writes: “For first of all we must prepare a natural and experimental history, sufficient and good; and this is the foundation of all, for we are not to imagine or suppose, but to discover, what nature does or may be made to do” (Novum organum, II aphorism 10).

But a natural history, a random collection of facts, is too unwieldy to work with directly. And so, Bacon suggests, “we must therefore form tables and arrangements of instances, in such a method and order that the understanding may be able to deal with them” (ibid.). Take, for example, the investigation of the nature of heat, the example that Bacon develops in most detail in the Novum organum. Bacon begins with what he calls the table of ‘Instances agreeing in the nature of heat’, or ‘Table of essence and presence’, in which are listed a variety of circumstances in which heat may be found, including fiery meteors, quicklime sprinkled with water, iron dissolved in acid, and fresh horse dung.

The second table is what Bacon calls ‘Instances in proximity where the nature of heat is absent’. In this table, Bacon examines one by one the entries in the table of essence and presence, and tries to find similar circumstances in which heat is absent. So, for example, connected with the observation that iron in acid produces heat, Bacon notes that softer metals, like gold and lead, do not give off heat when dissolved in acid. The third table is what Bacon calls the ‘Table of degrees’. Here Bacon makes observations about things that contain the nature of heat, for example, in greater or lesser degree. And so he observes that while old dung is colder than fresh dung, it has what Bacon calls a potential for heat insofar as it will produce heat when enclosed or buried, he claims. Similarly, Bacon observes that different substances burn with different degrees of heat.

Once we have compiled the natural history and arranged it into the proper tables, we are ready for the inductive step, at least the first inductive step, what Bacon calls the first vintage. At this point, Bacon says, “the problem is, upon a review of the instances, all and each, to find such a nature as is always present or absent with the given nature, and always increases and decreases with it” (ibid., II 15). That is, in the case of heat, we want to find that which is always present when heat is present, and always absent when heat is absent.

This proceeds in two stages. First, Bacon uses his tables to exclude possible natures. And so, for example, though Bacon thinks that heavenly bodies are hot, being a heavenly body cannot be part of the nature of heat, since there are terrestrial bodies which are hot as well. Once we have excluded candidates for the nature of heat in this way, we can then examine what is left, and say what it is that all hot things have in common. What Bacon suggests in the case at hand is that heat is a particular kind of motion: “heat is a motion, expansive, restrained, and acting in its strife upon the smaller particles of bodies, [...] not sluggish, but hurried and with violence” (ibid., II 20). This, Bacon claims, is what all instances of heat found in the tables of our natural history have in common.

After this, the Novum organum is not altogether clear where we go. Presumably the first vintage is followed by successive vintages, in which we press more knowledge of nature from our initial observations. Furthermore, Bacon suggests, the knowledge we have derived from experiment will in some way suggest to us new experiments to perform, though he doesn’t indicate how exactly this might work. It is important to note here that Bacon is not merely an advocate for the appeal to experience: many others were as well. Bacon saw his innovation as showing us how to use experience effectively, so that it could actually lead to knowledge of the real causes of things, that is, to a genuine science.

The method of the Novum organum is exemplified in the organization of the House of Salomon, the perfect scientific society that Bacon envisions in his science fiction story, the New Atlantis, published posthumously in 1627 appended to the Sylva sylvarum. At the bottom of the organization are those who form the tables of natural history, a total of twenty-four investigators. Twelve “merchants of light [...] sail into foreign countries under the names of other nations [and] bring us the books and abstracts, and patterns of experiments of all other parts”; three “depredators” collect experiments from books, three “mystery-men” collect experiments from mechanical arts and liberal sciences, and three “pioneers or miners” try new experiments of their own devising. They are joined by three “compilers” who arrange these observations and experiments into proper tables.

Twelve workers are employed at the next stage of the enterprise. Three “dowry-men or benefactors” examine the initial tables compiled by the compilers, and draw out both technological applications as well as the first theoretical conclusions that can be drawn from the tables, presumably what Bacon calls the ‘first vintage’ in the Novum organum. Three “lamps”, as he calls them, then draw new experiments out of the work of the compilers and benefactors, which experiments are then performed by three “inoculators”. And finally, “we have three that raise the former discoveries by experiments into greater observations, axioms, and aphorisms. These we call ‘interpreters of Nature’” (Bacon 1627, pp. 44-45).

Bacon’s empiricist program in the Novum organum and especially in the New Atlantis was the explicit model for the Royal Society of London when it was founded in 1660. Thomas Sprat opens his 1667 defense of the Royal Society, his The History of the Royal Society, with the following encomium to its inspiration:

I shall onely mention one great man, who had the true imagination of the whole extent of this Enterprize, as it is now set on foot; and that is, the Lord Bacon. In whose Books there are every where scattered the best arguments, that can be produc’d for the defence of Experimental Philosophy; and the best directions, that are needful to promote it. All which he has already adorn’d with so much Art; that if my desires could have prevail’d with some excellent Friends of mine, who engag’d me to this Work: there should have been no other Preface to the History of the Royal Society, but some of his Writings. (Sprat 1667, pp. 35-36)

The actual practice of the society reflected this interest in the empirical investigation of the world, in going back to the things themselves. The Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society are filled with empirical observations. The volume published in 1687, for example, contains a report of the publication of Newton’s Principia, as well as many articles on topics in pure and mixed mathematics. But it also includes a great number of other things, including an account of an hermaphrodite from Tholose, wheat said to have fallen in rain in Wiltshire, an article about why the Moon appears greater near the horizon, an investigation of the celerity of the circulation of the blood, a report of ducks bred underground, a report on the natural history of Staffordshire, and other natural historical reports and curiosities. Indeed, the Philosophical Transactions included not only natural historical reports, but historical reports of a much more general kind, including a report on an essay towards the recovery of the Jewish weights and measures, an article on the Great Wall of China described, and an odd inscription found on the base of a pillar at Rome.

An important feature of the use of experience in the seventeenth century is the distinction between observation and experiment. For the Aristotelian natural philosopher, physics is the study of natural bodies considered as natural bodies, that is, as having internal principles of motion and rest. As a consequence, it was important to observe them as they naturally behave, as they are in themselves. Nothing can be gained from subjecting them to unnatural qualities. For example, to heat water or earth, both elements that are by their natures cold, can tell us nothing about what they are in themselves. But it is quite different for various of the competing programs. For the alchemist, it is subjecting bodies to intense heat that enables us to separate them into their elements, and find their true elements. It is for this reason that Severinus tells us to “purchase coal, build furnaces, watch and operate with the fire without wearying. In this way, and no other, you will arrive at a knowledge of things and their properties”.

Similarly, Nicasius Le Febure [Le Fèvre] writes in his popular alchemical textbook, A compleat body of chymistry (1664), that fire is the primary aid that the alchemist has to carry out his primary goal of separating any piece of matter into its ultimate elements:

For as the Anatomist doth make use of Rasors and other sharp Tools in his Dissections, to separate the better the several parts of the human body, which is his chief object: The same doth the Chymical Artist, fetching his instruction from Nature it self, to attain his end, which is nothing else but to joyn homogeneal and separate heterogeneal things by means of Heat; […] for the fire never relents or slackens its action, but rather drives it on and encreaseth it, untill he finds no heterogentity left in the Compound. (1664, p. 19)

In this way, it is by subjecting bits of matter to the fire that we can learn their real nature. For the mechanical philosopher Descartes, there is no difference between the artificial and the natural: “I do not recognize any difference between artifacts and natural bodies except that the operations of artifacts are for the most part performed by mechanisms which are large enough to be easily perceivable by the senses” (Descartes, Principia philosophiae, IV 203).

As a consequence of this view, too, we can learn about the material world either through observation or through manipulation. But it is Bacon who puts the point with the greatest generality. He writes: “For even as in the business of life a man’s disposition and the secret workings of his mind and affections are better discovered when he is in trouble than at other times; so likewise the secrets of nature reveal themselves more readily under the vexations of art than when they go their own way” (Bacon, Novum organum, I 98). It is thus by torturing Nature that we learn its deepest secrets, by concocting experiments and seeing what happens, rather than by simply observing Nature in its normal course.

The use of experiment, rather than just observing the normal course of Nature, is a hallmark of seventeenth-century science, something that separates it in an important way from what preceded. This new attitude can be seen in Galileo’s (and Mersenne’s) experiments with pendula and bodies on inclined planes, with Descartes’ optical experiments on prisms and flasks of water in connection with his theory of the rainbow, with Torricelli’s and Pascal’s experiments on tubes of mercury and other liquids, with Boyle’s air pump experiments, with Newton’s optical experiments, and in many, many other instances. In a number of these cases, scientists examined situations that could be said to be unnatural in the extreme, situations that could only be created in the laboratory, with the explicit creation by scientists of circumstances that do not otherwise exist in Nature, at least on Earth.

As we have argued, in the seventeenth century, appeals to experiment and experience became increasingly important. But there is also another change worth mentioning here, a change in the very concept of experience itself that underlay the empirical programs of the century. While the Aristotelian appealed to experience, it was generally experience understood as the common course of Nature, what everyone knew from their everyday dealings with the world. Experience, phenomena, in this sense, represent not individual observations but the collective wisdom that we get from the unanimity of individual observations. Thus Aristotle wrote in the Posterior Analytics: “So from perception there comes memory, as we call it, and from memory (when it occurs often in connection with the same thing), experience; for memories that are many in number form a single experience” (II.19, 100a5-7).

Aristotelian science is grounded not in individual events of sensory experience, particular observations made on particular occasions, but on the general course of experience, on common assent. It is not sufficient for an Aristotelian science that we have a particular observation that it snowed on the morning of January 23, 1979 in Stockholm, or that on September 26, 1664, a particular apple was observed to fall from a tree and hit one Isaac Newton on the head. What is necessary for Aristotelian science is that it be generally accepted that it snows in northern climes in the winter months, or that heavy bodies fall; this is what constitutes experience, properly speaking, as opposed to mere perception. And to go from perception, the individual deliverance of the senses on a particular occasion, to experience, properly speaking, requires the repetition of these individual perceptions. Should these individual perceptions speak with sufficient unanimity, then memory will transform them into experiential facts, facts that can be acknowledged by common consensus, and used as the foundation of a genuine body of knowledge. In this way, an experimental fact can be regarded as a kind of low-level general statement, established by repetition.

With such experiential facts drawn from uniform common experience, there is little chance for controversy: the reader can be expected to have the same experience that the scientist has. Experience here can be viewed as a point of common agreement on which the Aristotelian scientist can build his case. But in the seventeenth century, along with the rise of new and contentious views of the world, this changes. The kinds of phenomena to which a scientist appeals are increasingly phenomena of a very specialized sort, phenomena, like those that arise within the vacuum chamber of the air pump that only a few people have access to, or phenomena, like the observations made on pond water with the newly discovered microscope that are quite surprising and counter to everyday experience. It thus becomes increasingly a problem to establish the credibility of observations and experimental phenomena; common consensus and common experience no longer suffice. Experience can no longer be regarded as a point of common agreement; the scientist must convince the reader that the phenomena he is presenting are, indeed, true representations of the way things are.

It is, perhaps, because of this that increasingly reports are given not in general terms, “such-and-such happens when you do such-and-such”, but in terms of the personal experience of a single observer. This is evident in this typical report that Robert Boyle gives of one of the experiments he performed with his air pump. In that experiment, Boyle put a lark into his apparatus, and then evacuated the air. This is what he reports:

We took (being then unable to procure any other lively bird, small enough to be put into the receiver) a lark, one of whose wings had been broken by a shot of a man that we had sent to provide us some birds for our experiment; but notwithstanding this hurt, the lark was very lively, and did, being put into the receiver, divers times spring up in it to a good height. The vessel being hastily, but carefully closed, the pump was diligently plied, and the bird for a while appeared lively enough; but upon a greater exsuction of the air, she began manifestly to droop and appear sick, and very soon after was taken with as violent and irregular convulsions, as are wont to be observed in poultry, when their heads are wrung off: for the bird threw herself over and over two or three times, and died with her breast upward, her head downwards, and her neck awry. [...] we found that the whole tragedy had been concluded within ten minutes of an hour, part of which time had been employed in cementing the cover to the receiver. (Boyle 1662, p. 97)

This is very, very different from just saying, as one might in an earlier account, that larks (or birds, or animals) die when the air is evacuated from their environment. In this account, we see exactly what Boyle did, and exactly what he, on that particular occasion, saw. In this way the credibility of the report is, in a sense, parasitic on the credibility of Boyle himself; it is because Boyle is trusted that the report is as well. Furthermore, the vivid descriptions of the experimental procedure in a sense place the reader on the spot and make him or her what might be called a ‘virtual witness’ of the outcome of an experiment.

This leads to another tendency in the period, which is the increasingly social nature of observation. For a Descartes or a Bacon, for example, it is enough for a reliable witness to report his or her observations. However, this is explicitly rejected by the Royal Society. In The History of the Royal Society, Sprat reports, for example, that experiments are to be performed multiple times, by different experimenters, and then presented to the Royal Society as a whole to determine whether or not the experimental fact has been established. When the Royal Society took it upon itself to sponsor an experiment or series of experiments, it was a matter of policy, Sprat reports, that a number of different members be involved. Experiments were organized, Sprat writes:

either by allotting the same Work to several men, separated one from another; or else by joyning them into Committees […]. By this union of eyes, and hands there do these advantages arise. Thereby there will be a full comprehension of the object in all its appearances; and so there will be a mutual communication of the light of one Science to another: whereas single labours can be but as a prospect taken upon one side. And also by this fixing of several mens thoughts upon one thing, there will be an excellent cure for that defect, which is almost unavoidable in great Inventors. It is the custom of such earnest, and powerful minds, to do wonderful things in the beginning; but shortly after, to be overborn by the multitude, and weight of their own thoughts; then to yield, and cool by little and little; and at last grow weary, and even to loath that, upon which they were at first the most eager […]. For this the best provision must be, to join many men together. (Sprat, pp. 84-85)

The claim that experiments must be done by a number of different hands is quite explicit and quite carefully thought out; it is only if a number of different people are involved in carrying out experiments and replicating the experiments others submit that we can avoid the errors that inevitably creep in if only one experimenter is involved. In addition to the claim that experiments must be repeated by a variety of hands, Sprat further reports that experimental facts must be established through the consensus of the community as a whole. He writes:

[after the performance of an experiment] comes in the second great Work of the Assembly; which is to judg, and resolve upon the matter of Fact. In this part of their imployment, they us’d to take an exact view of the repetition of the whole course of the Experiment […]; never giving it over till the whole Company has been fully satisfi’d of the certainty and constancy; or, on the otherside, of the absolute impossibility of the effect. This critical, and reiterated scrutiny of those things, which are the plain objects of their eyes; must needs put out of all reasonable dispute, the reality of those operations, which the Society shall positively determine to have succeeded. [T]here is not any one thing, which is now approv’d and practis’d in the World, that is confirm’d by stronger evidence, than this, which the Society requires; except onely the Holy Mysteries of our Religion. (ibid., pp. 99-100)

Experimental facts are now established by the community as a whole. It is no accident that we refer here to what goes on in the Royal Society. These new standards of experimental facthood require new institutions. If the establishment of an experimental fact requires the repetition of the experiment by different hands, and its final determination by the assembled group of experts, then we must have a criterion of expertise, and institutions that can determine who is a qualified experimenter, qualified to reproduce experiments, and who is qualified to pass on the success or failure of an experiment in establishing experimental facthood. It is no surprise, then, that the new conceptions of experiment and experience grew along with the scientific academies in the second half of the seventeenth century.

One should not overestimate the importance of experience for the scientific revolution of the seventeenth century. Though the new astronomical observations of Tycho (through the lens of Kepler’s new planetary theories) and telescopic observations of Galileo had their role to play, Copernicanism was as much a question of theoretical reasoning as it was a question of new observations. Though Boyle, for example, attempted to present experimental evidence for the new mechanical and corpuscular view of matter, and against the Aristotelian view of body as matter and form, the corpuscular philosophy had little in the way of real, hard empirical results to show. Where the Aristotelian might attribute an empirical phenomenon to an unknown form, the mechanist might attribute it to an unknown corpuscular substructure. This seems little advance. But nevertheless, something important happened with respect to experience and experiment and its role in science in this period.

For a strict Aristotelian, certainty was central to the very idea of a science. For example, in his Summa philosophiae quadripartita, Eustachius gives three conceptions of what it is to be a science. The first, “impropria et latissima”, takes science “pro quacunque rei vera cognitione”. The second, “propria et minus confusa”, takes science “pro cognitione rei vera et evidenti per quamlibet causam”. On the third, and “maxime propria et adhuc minus late patens”, “Scientiae est acceptio pro cognitione certa et evidenti rei necessariae per propriam causam et necessariam à qua res verè et secundùm naturam dependeat”. (Eustachius 1648, Logica, p. 5)

When evaluating this definition of a science, though, one must remember that the term ‘science’ (that is, the Latin term scientia) is meant to be understood much more broadly than the corresponding term in modern languages. For example, both logic and theology would normally have been considered sciences in this broad sense. In order to include physics or natural philosophy among the sciences, though, one had to stretch the definition a bit. In his discussion of whether or not physics is a science, properly speaking, Eustachius concludes that it is. But in response to the objection that not everything in physics is certain and demonstrated from first causes, Eustachius notes: “ut aliqua totalis disciplina verè dicatur scientia, satis est ut nonnulla, licèt non omnia, in illa certò sciantur; et per veras causas demonstrentur, licèt non adeò accuratas: neque enim ad rationem scientiae propriè dictae requiruntur semper accuratae demonstrationes, sed tales quales rerum natura patitur” (Physica, p. 111).

That is to say, physics counts as a science because some parts of it are genuinely certain. The whole of physics need not be properly demonstrated as certain in order for it to be counted as a science, strictly speaking. In practice, the standards for certainty in a science didn’t always apply. The lack of certainty in natural philosophy in practice contrasted sharply with the certainty of which the mathematical sciences were capable. This contrast was pointed out in no uncertain terms by the Jesuit mathematician Christopher Clavius. In the proemium to his collected mathematical writings, Clavius writes:

Mathematicae disciplinae sic demonstrant omnia, de quibus suscipiunt disputationem, firmissimis rationibus, confirmantque, ita ut vere scientiam in auditoris animo gignant, omnemque proprsus dubitationem tollant: id quod aliis scientiis vix tribuere possumus, cum in eis saepenumero intellectus multitudine opinionum ac sententiarum varietate in veritate conclusionum judicanda suspensus haereat atque incertus. Hujus rei fidem faciunt tot Peripateticorum sectae (ut alios interim Philosophos silentio involvam) quae ab Aristotele, veluti rami e trunco aliquo, exortae, adeo et inter se, et nonnunquam a fonte ipso Aristotele dissident, ut prorsus ignores, quidnam sibi velit Aristoteles, num de nominibus, an de rebus potius disputationem instituat. (Clavius 1611-1612, vol. 1, p. 5)

More generally, Clavius, one of the authors of the Jesuit Ratio studiorum, the curriculum that was to be followed in Jesuit schools throughout Europe, called upon students of natural philosophy to study the mathematical sciences, and for the mathematical sciences and their teachers to have greater status within the Jesuit colleges and within the curriculum.

One student of the Jesuits who learned this lesson well was René Descartes. In his Discours de la méthode, Descartes complained about the uncertainty of what he had been taught in school. He singled out philosophy here, the subject that comes closest to science in the modern sense. He writes:

Je ne dirai rien de la philosophie, sinon que, voyant qu’elle a été cultivée par les plus excellents esprits qui aient vécu depuis plusieurs siècles, et que néanmoins il ne s’y trouve encore aucune chose dont on ne dispute, et par conséquent qui ne soit douteuse, je n’avais point assez de présomption pour espérer d’y rencontrer mieux que les autres; et que, considérant combien il peut y avoir de diverses opinions, touchant une même matière, qui soient soutenues par des gens doctes, sans qu’il y en puisse avoir jamais plus d’une seule qui soit vraie, je réputais presque pour faux tout ce qui n’était que vraisemblable. Puis, pour les autres sciences, d’autant qu’elles empruntent leurs principes de la philosophie, je jugeais qu’on ne pouvait avoir rien bâti, qui fût solide, sur des fondements si peu fermes. (Descartes 1637, p. 10)

Descartes thus resolved to reject everything that is merely probable. It is important here to realize that the notion of the probable in the seventeenth century was complex, and not exactly our own, and involved elements of authority as well as opinions that could not be supported by demonstrative argument (see appendix: boxed text on probability). But be that as it may, it is clear that Descartes (at least in his earlier writings) sought genuine certainty in his scientific endeavors. This is even clearer in his early Regulae ad directionem ingenii, a treatise on method that Descartes worked on in the 1620s, but abandoned without publishing. There he wrote:

Circa illa tantum objecta oportet versari, ad quorum certam et indubitatam cognitionem nostra ingenia videntur sufficere. Omnis scientia est cognitio certa et evidens; neque doctior est qui de multis dubitat, quam qui de iisdem nunquam cogitavit, sed nihilominus eodem videtur indoctior, si de aliquibus falsam concepit opinionem; ac proinde nunquam studere melius est, quam circa objecta adeo difficilia versari, ut, vera a falsis distinguere non valentes, dubia pro certis cogamur admittere, cum in illis non tanta sit spes augendi doctrinam, quantum est periculum minuendi. Atque ita per hanc propositionem rejicimus illas omnes probabiles tantum cognitiones, nec nisi perfecte cognitis, et de quibus dubitari non potest, statuimus esse credendum. (Descartes, 1964-1974, vol. X, p. 362)

Descartes’ response to the uncertainty of scholastic science is to demand an even higher degree of certainty than his teachers did. In this way, Descartes’ ambition was to bring the certainty of the mathematical disciplines to natural philosophy itself. In this way Descartes can be seen as a reformer of the scholastic Aristotelian tradition, holding it to its own standards.

But Descartes ultimately found that he could not actually produce such a science. In the face of reality, an intransigent world that would not yield up its secrets, Descartes’ demands for certainty seem to moderate. By the end of his Principia philosophiae, Descartes seems to relax the demands for certainty, and admit a lower standard for the natural sciences. In the Principia, Descartes found that he had to proceed not by certain deductions from first causes, but by hypothesizing hidden mechanisms, and then deducing phenomena from those hypotheses. In this circumstance, he had to admit that our knowledge of these underlying mechanisms was less than fully certain. He wrote:

Que, touchant les choses que nos sens n’aperçoivent point, il suffit d’expliquer comment elles peuvent être; et que c’est tout ce qu’Aristote a tâché de faire. On répliquera encore à ceci que, bien que j’aie peut-être imaginé des causes qui pourraient produire des effets semblables à ceux que nous voyons, nous ne devons pas pour cela conclure que ceux que nous voyons sont produits par elles. Parce que, comme un horloger industrieux peut faire deux montres qui marquent les heures en même façon, et entre lesquelles il n’y ait aucune différence en ce qui paraît à l’extérieur, qui n’aient toutefois rien de semblable en la composition de leurs roues: ainsi il est certain que Dieu a une infinité de divers moyens, par chacun desquels il peut avoir fait que toutes les choses de ce monde paraissent telle que maintenant elles paraissent, sans qu’il soit possible à l’esprit humain de connaître lequel de tous ces moyens il a voulu employer à les faire. [...] Et je croirai avoir assez fait, si les causes que j’ai expliquées sont telles que tous les effets qu’elles peuvent produire se trouvent semblables à ceux que nous voyons dans le monde, sans m’enquérir si c’est par elles ou par d’autres qu’ils sont produits. Même je crois qu’il est aussi utile pour la vie, de connaître des causes ainsi imaginées, que si on avait la connaissance des vraies: car la médecine, les mécaniques, et généralement tous les arts à quoi la connaissance de la physique peut servir, n’ont pour fin que d’appliquer tellement quelques corps sensibles les uns aux autres, que, par la suite des causes naturelles, quelques effets sensibles soient produits; ce que nous ferons tout aussi bien, en considérant la suite de quelques causes ainsi imaginées, bien que fausses, que si elles étaient les vraies, puisque cette suite est supposée semblable, en ce qui regarde les effets sensibles. [Principia philosophiae, IV, p. 204]

In this way Descartes seems to give up the ambition of his early thought, a science completely certain, and admit that our knowledge of the physical world is only probable.

In this, Descartes comes to agree with a more general trend in the seventeenth century. For the schoolmen, natural philosophy constituted a science because at least some part of it could attain genuine certainty. But a number of Descartes’ contemporaries rejected even this modest claim. Marin Mersenne, for example, expressed general scepticism about our ability to penetrate to the real causes in physics. In his Questions inouyes (1634), Mersenne poses the following question: “Peut-on sçavoir quelque chose de certain dans la Physique?” He answers it as follows:

Il n’y a rien plus clair et plus evident que la lumiere luit, et que les pierres descendent vers le centre de la terre, et neantmoins on ne sçait pas encore si elles descendent par leur pesanteur, ou si elles sont chassees par l’air, et par tous les corps qui sont dessus, ou si elles sont attirées par la terre: On ne sçait pas aussi comment la lumiere esclaire, ny comme elle eschauffe. […] Car on ne peut dire que l’on sçache aucune chose comme il faut, selon les loix et les notions qu’Aristote, et les autres Philosophes donnent de la science, si l’on ne demonstre qu’il est impossible que la raison que l’on apporte, ou que la chose que l’on propose, ne soit vraie. Ce qui suffit pour persuader à ceux qui usent de reflexion, qu’il n’y a rien de certain dans la Physique, ou qu’il y a si peu de choses certaines, qu’il est difficile d’en proposer. (Mersenne 1634, qu. 18)

In this regard, Mersenne seems to go even farther than Descartes, for whom we can have at least some probable knowledge of causes in physics. Mersenne’s views are echoed in those of his friend and colleague in arms, Pierre Gassendi. In his early attack on Aristotelianism, his Exercitationes paradoxicae adversus Aristoteleos (1624), Gassendi explicitly denied the possibility of an Aristotelian science. One exercise is entitled, “quod nulla sit Scientia, et maxime Aristotelea”. Article 6 of that exercise goes on to argue that we cannot know the real nature of things, but only their appearances: “Sciri tantum posse quale his aut illis appareat”. (Gassendi 1624, pp. 192A, 203A). This is a view that Gassendi held throughout his career, one that can be found in his last major works, the Animadversiones in decimum librum Diogenis Laertii (1649), an edition of and commentary on Epicurean texts found in Diogenes Laertius, and in the posthumously published Syntagma philosophicum (1658), which drew heavily on the Animadversiones.

This view is nicely expressed by Walter Charleton, an English follower of Gassendi (and Descartes as well!), who, in Physiologia (1654), paraphrases Gassendi as follows:

We are Men, i.e. Moles; whose weak and narrow Opticks are accommodated only to the inspection of the exterior and low parts of Nature, not perspicacious enough to penetrate and transfix her interior and abstruse Excellencies: nor can we speculate her glorious beauties in the direct and incident line of Essences and Formal Causes, but in the refracted and reflected one of Effects; nor that, without so much of obscurity, as leaves a manifest incertitude in our Apprehensions, and restrains our ambition of intimate and apodictical Science, to the humble and darksome region of mere superficial Conjecture. Such being the condition of our imperfect Intellectuals; when we cannot explore the profound recesses, and call forth the Formal Proprieties of some Natures, but find our disquisitive Faculties terminated in the some Apperences, or Effects of them. (Charleton 1654, pp. 50-51)

Charleton’s and Gassendi’s view finds its full expression at the end of the century in the enormously influential work of John Locke, his Essay concerning humane understanding (1690). In that work, Locke writes:

And therefore I am apt to doubt, that how far soever human industry may advance useful and experimental philosophy in physical things, scientifical will still be out of our reach; because we want perfect and adequate ideas of those very bodies which are nearest to us, and most under our command. […] Several effects come every day within the notice of our senses, of which we have so far sensitive knowledge; but the causes, manner, and certainty of their production […] we must be content to be very ignorant of. In these we can go no farther than particular experience informs us of matter of fact, and by analogy to guess what effects the like bodies are, upon other trials, like to produce. But as to a perfect science of natural bodies […] we are, I think, so far from being capable of any such thing, that I conclude it lost labour to seek after it. (Locke 1690, bk. IV, chapt. 3, sects. 26 and 29)

Locke is expressing here what has become the general concensus of the scientific community by the end of the century. Even Gottfried Leibniz, who believed that certain parts of science, the basic laws of nature, for example, could be known with certainty, was forced to admit that “nous ne sommes qu’Empiriques dans les trois quarts de nos Actions”. (Leibniz 1714, sect. 28). Responding to Locke’s pessimism about knowledge and the possibility of a science of body in his Nouveau essais, Leibniz cheerfully recommended simply accepting the lower degree of certainty that we get from the senses as a kind of knowledge, and developing the new science of probability as a logic for science so conceived:

je tiens que la recherche des degrés de probabilité seroit très importante et nous manque encor, et c’est un grand defaut de nos Logiques. Car lorsqu’on ne peut point decider absolument la question, on pourroit tousjours determiner le degré de vraisemblance ex datis, et par consequent on peut juger raisonnablement quel parti est le plus apparent. (ibid., sect. 14)

As the remarkable discoveries of the century increased, the increased realization of the complexity of Nature drove scientists to the view that we must content ourselves with uncertainty and probability. The earlier demand for certainty that Descartes had inherited from his Aristotelian teachers had proved unattainable.

At the beginning of the century, Europeans lived in a largely Aristotelian world of matter and form, celestial and terrestrial, living things infused with souls, a view supported by common experience and traditional syllogistic reasoning. By the end of the century, though, much had changed. While Aristotelianism was still very much in evidence, especially within the universities, it was on the run. In most serious intellectual circles Aristotelianism had been replaced by a new, mechanistic and mathematical world, supported by a richer body of empirical evidence. In an obvious way, this marks the beginning of the world of modern science.

Daniel Garber

- Biagioli 1989: Biagioli, Mario, The social status of Italian mathematicians, 1450-1600, “History of science”, 27, 1989, pp. 41-95.

- Clericuzio 2000: Clericuzio, Antonio, Elements, principles, and corpuscles: a study of atomism and chemistry in the seventeenth century, Dordrecht, Kluwer, 2000.

- Copenhaver 1992: Copenhaver, Brian P. - Schmitt, Charles, Renaissance philosophy, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1992.

- – 1998: Copenhaver, Brian P., The occultist tradition and its critics, in: The Cambridge history of seventeenth-century philosophy, edited by Daniel Garber, Michael Ayers, Cambridge-New York, Cambridge University Press, 1998, 2 v.; v. II, pp. 454-512.

- Dear 1995: Dear, Peter, Discipline and experience. The mathematical way in the scientific revolution, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1995.

- Deman 1933: Deman, Thomas, Probabilis, “Revue des sciences philosophiques et théologiques”, 22, 1933, pp. 260-290.

- Garber 1979: Garber, Daniel - Zabell, Sandy, On the emergence of probability, “Archive for the history of exact sciences”, 21, 1979, pp. 33-53.

- – 2001: Garber, Daniel, Experiment, community, and the constitution of nature in the seventeenth century, in: Garber, Daniel, Descartes embodied. Reading Cartesian philosophy through Cartesian science, Cambridge-New York, Cambridge University Press, 2001, pp. 296-328.

- Grant 1979: Grant, Edward, The condemnation of 1277, God’s absolute power, and physical thought in the late Middle Ages, “Viator”, 10, 1979, pp. 211-244.

- Hacking 1975: Hacking, Ian, The emergence of probability. A philosophical study of early ideas about probability, induction and statistical inference, London, Cambridge University Press, 1975 (trad. it.: L’emergenza della probabilità. Ricerca filosofica sulle origini delle idee di probabilità, induzione e inferenza statistica, trad. di Martina Piccone, Milano, Il Saggiatore, 1987).

- Kraye 1996: The Cambridge companion to Renaissance humanism, edited by Jill Kraye, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- Kristeller 1964: Kristeller, Paul O., Eight philosophers of the Italian Renaissance, Stanford (Cal.), Stanford University Press, 1964.

- Lennox 1986: Lennox, James G., Aristotle, Galileo, and ‘mixed sciences’, in: Reinterpreting Galileo, edited by William A. Wallace, Washington (D.C.), Catholic University of America Press, 1986, pp. 29-51.

- Meinel 1988: Meinel, Christoph, Early seventeenth-century atomism. Theory, epistemology, and the insufficiency of experiment, “Isis”, 79, 1988, pp. 68-103.

- Rose 1975: Rose, Paul L., The Italian Renaissance of mathematics. Studies on humanists and mathematicians from Petrarch to Galileo, Genève, Droz, 1975.

- Shapin 1985: Shapin, Steven - Schaffer, Simon, Leviathan and the air-pump. Hobbes, Boyle and the experimental life, including a translation of Thomas Hobbes’ Dialogus physicus de natura aeris by Simon Schaffer, Princeton (N.J.), Princeton University Press, 1985.

- – 1994: Shapin, Steven, A social history of truth. Civility and science in seventeenth-century England, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1994.

- Westman 1980: Westman, Robert S., The astronomer’s role in the sixteenth century. A preliminary study, “History of science”, 18, 1980, pp. 105-147.